WASHINGTON—Proposed new minimum training for 737 MAX pilots includes five scenarios in full-flight simulators preceded by reviews of related checklists and materials, a report issued by the FAA Oct. 6 reveals.

The draft Flight Standardization Board (FSB) document, which covers all 737s, adds “special emphasis training” that focuses on the MAX family’s revamped flight control computer software, including the maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) flight control law. All pilots transitioning to the MAX or flying it following its grounding will have to undergo the training, including a demonstration of the MCAS, which provides automatic nose-down horizontal stabilizer commands during certain flight profiles.

Inadvertent MCAS activations played key roles in two fatal MAX accidents that left the fleet grounded and prompted regulators to order software and training changes. Previous versions of the FSB did not require any simulator work for pilots with 737 experience transitioning to the MAX—part of Boeing’s philosophy to minimize training costs for current 737 customers. They also did not call for any MCAS training, and Boeing did not include any information on the system in 737 MAX flight crew operations manuals, so most pilots did not know it existed until after the first accident, Lion Air Flight 610 in October 2018. Instructions from Boeing and the FAA following the accident that emphasized existing checklists were not sufficient enough to help the crew of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 manage an MCAS-related failure scenario in March 2019 that also ended in disaster and triggered the global fleet ban.

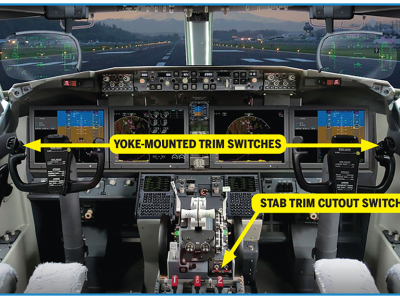

The proposed updated training includes a review of the revamped MCAS as well as demonstrations of it at work. Related failure scenarios also must be practiced in the simulator—a recommendation that Boeing long resisted but ultimately made in January 2020, following revelations that the company discouraged at least one customer—Lion Air—that felt its pilots needed the additional training. The proposed simulator work includes manual trimming during a runaway stabilizer event, manual trimming during an approach and go-around, erroneous angle-of-attack (AOA) data on takeoff that triggers an unreliable airspeed warning, and activation of a new STAB OUT OF TRIM alert.

Pilots also must review seven checklists and training material being updated as part of Boeing’s proposed changes, which include revamping the MCAS to ensure it will not activate repeatedly and create the runaway-stabilizer condition that overwhelmed the crews in both accident sequences.

While most of the proposed changes are linked to the MCAS and MAX-specific changes affecting the flight control computers, some of the scenarios—notably the manual-trim scenarios—could apply to older 737 models. The updated FSB does not propose any new training on older 737 models, however.

The draft FSB also says that a recent joint evaluation by Brazilian, Canadian, European, and U.S. regulators deemed the new MCAS software “operationally suitable,” or ready for roll-out. The team of regulators noted issues with one checklist, Airspeed Unreliable, that the FAA will review. Among the issues: noted thrust settings for a potential go-around are not clear, and a change to behavior of flight directors—graphic images that guide pilots to proper pitch and bank angles—may not be clear to pilots.

The FAA is accepting comments on the draft FSB through Nov. 2. Finalizing the FSB—which will guide all MAX pilot training—is one of the last major steps in the 19-month process to win regulatory approval for the Boeing model’s return to service.

Comments

MCAS 1.0 did in fact do exactly what it was designed to do and expected (if they had looked at it) with a single failed AOA.

Negligent design lead to it doing so. You could not have done worse if you had intended to. That is truly the sad reality of Boeing's failure.