Pilot groups and at least one regulator have raised concerns about several non-normal pilot procedures being changed following a review of the grounded Boeing 737 MAX that also apply to older versions of the venerable narrowbody.

Boeing’s proposed modifications to the MAX in response to two fatal accidents affect the model’s flight control computer software, manuals, and pilot training. While the software changes apply only to the MAX variant, several non-normal checklists being updated are the same for the MAX and the 737 Next Generation (NG). Two in particular—runaway stabilizer and airspeed unreliable—have been highlighted by several commenters that weighed in on the FAA’s proposed requirements that would codify Boeing’s changes.

The United Arab Emirates’ General Civil Aviation Authority (GCAA) told the FAA it is concerned about a lack of understanding around factors that affect manual movement, or trimming, of the horizontal stabilizer. “The manual wheel trim forces were certified by analysis and not by flight testing (or tested on non-B737MAX aircraft),” the GCAA told the FAA in comments. “Heaviness on the manual wheel trim following a failure, like runaway stabilizer, must be fully understood and experienced by crew during training and test.”

Used when automatic stabilizer trim motors fail or are de-activated by pilots troubleshooting an issue—and, crucially, a key step on the runaway stabilizer checklist—applying manual trim requires pilots to rotate a crank attached to a spool-shaped wheel in the cockpit. Analysis of factors highlighted in the MAX accidents revealed that aerodynamic forces can make the wheel difficult to turn.

The FAA conducted flight tests in mid-2019 to evaluate the issue, and flagged it as needing further review. One of the results will be updates to Boeing’s 737 flight crew operations manual (FCOM) and training documents that highlight, in general, possible difficulties with manually trimming in certain situations.

The GCAA expressed frustration with the lack of specifics that could help industry better understand the issue.

“The least FAA and Boeing can do is to assist the authority and the operator by providing necessary data associated to this certification and manual trim techniques,” the UAE regulator said.

A representative from one U.S. pilots’ group told Aviation Week that its concern over the same issues led it to ask the FAA for data from the 2019 trials not long after they were completed. The agency has not provided it.

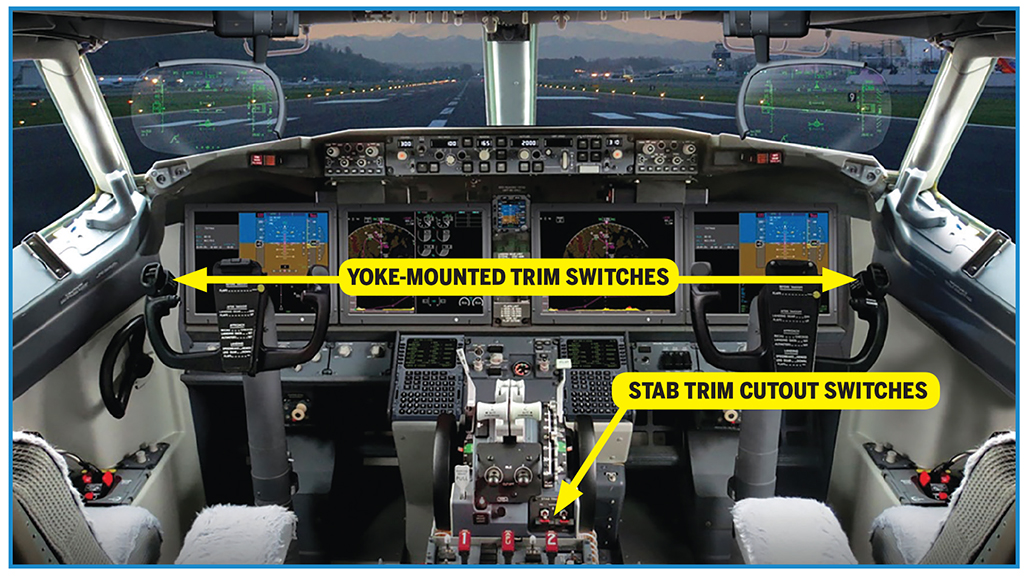

The Allied Pilots Association (APA) that represents American Airlines pilots is among those concerned about a related issue—teaching pilots how to reduce forces on the stabilizer so the trim wheel is easier to turn manually. If pilots facing a runaway stabilizer do not immediately counteract uncommanded inputs using yoke-mounted trim switches before disconnecting the trim motor, forces on the stabilizer can make it more difficult to adjust manually.

“The checklist should include a note that if the method of reducing airspeed to reduce air loads on the stabilizer fails to allow manual trimming (as a result of excessive stabilizer loads created by elevator pressure), slowly relaxing the control column pressure can reduce the load making manual trimming possible,” APA said.

Boeing included details of a similar procedure, which it called the “roller coaster” technique, in manuals for some of its early jets, including the 707 and the 737-100/200, but current manuals do not discuss it in detail. APA and the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) are among those pushing to get similar instructions put back in the 737 manual. Boeing’s proposed change to the 737 FCOM is a general note advising pilots to consider reducing airspeed to lessen aerodynamic forces on the stabilizer.

“This note does not provide any information for the flight crew to consider how much of an airspeed decrease will be necessary,” said comments filed by ALPA, which represents pilots at several 737 MAX operators, including Air Canada, United Airlines, and WestJet Airlines. “For horizontal stabilizers out of trim by a large magnitude, aircraft can quickly become difficult to manage at high airspeeds. ALPA believes guidance should be provided to the flight crew as to a specific targeted reduced airspeed.”

ALPA also expressed concern over Boeing’s language on the runaway stabilizer and stabilizer inoperative checklists that says both pilots may need to turn the manual trim wheel simultaneously to generate enough leverage to move the stabilizer.

“ALPA believes that a scenario where both pilots are required to provide manual inputs to a safety-critical flight control system during a non-normal event is not an ideal response to that event,” the association said. “During non-normal events it is commonly trained that one pilot continues to maintain the safe flight of the aircraft while the other pilot conducts the completion of related checklists, such as the [quick-reference handbook]. To interrupt this paradigm by requiring a two-pilot intervention on a safety-critical flight system cannot maintain the same level of safety.”

The British Airline Pilots Association expressed similar concerns in comments it filed earlier this month.

ALPA added that “if scenarios exist where the two-pilot intervention is not deemed extremely improbable,” Boeing should be forced “to implement design changes so that a two-pilot intervention is not required.”

Manual-trim procedures are especially crucial during one rare but long-acknowledged failure scenario. The yoke-mounted electric trim switches are designed so that one cannot override the other. If one fails, such as by shorting out while commanding nose-down stabilizer inputs, the other can be used to stop those inputs, but not reverse them.

“This has the potential to leave pilots with much heavier stick forces arising from greater air loads on the horizontal stabilizer, thereby increasing the effort required to trim manually, as directed later in the procedure,” APA said. “This unique malfunction should be noted in the [runaway stabilizer] checklist, as the ability to use the main electric stabilizer trim to reduce control column forces is not available in all runaway stabilizer events.”

Boeing’s revamp of the MAX flight control computer software began following the October 2018 crash of Lion Air Flight 610, a 737-8, and focused on the maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) flight control law. Following the March 2019 crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, another 737-8, and the MAX fleet’s global grounding, the FAA ordered Boeing to expand its work beyond the MCAS—quickly identified as a common link between the accidents—and examine related failure scenarios such as runaway stabilizer as well as how pilots are trained to manage them. Each of the checklist changes stem from the expanded work, but only two of the eight modified checklists were changed to align with the MAX-specific software alterations.

While the FAA is focused on reviewing Boeing’s proposed changes in light of how they affect the 737 MAX, the agency has said it will consider expanding any beneficial changes to the rest of the 737 fleet.

“Ancillary changes that can enhance the 737NG will also be reviewed by Boeing,” the FAA said in its “preliminary summary” of its 737 MAX review released in early August. “The FAA will work with Boeing to ensure that any issues related to the 737 MAX design change that may apply to the 737NG will be addressed as applicable.”

Comments

It's time for the FAA to end this charade and require specific training and a seperate type rating for the 737 MAX.

So .. no more toilet visits for 737NG/MAX pilots?

The MAX had a lot of safe trips landed beside the 2 tragic events.

But in aviation, there is zero tolerance for failure. My hope is that the solutions to be implemented will make the MAX a very much safer airliner.

That is a huge leap in crash rated (not accidents ) so, no, that lots of safe flights dog does not hunt.

Any time there was an AOA fault you were going to have a crisis at best and as we saw, crash at worst.