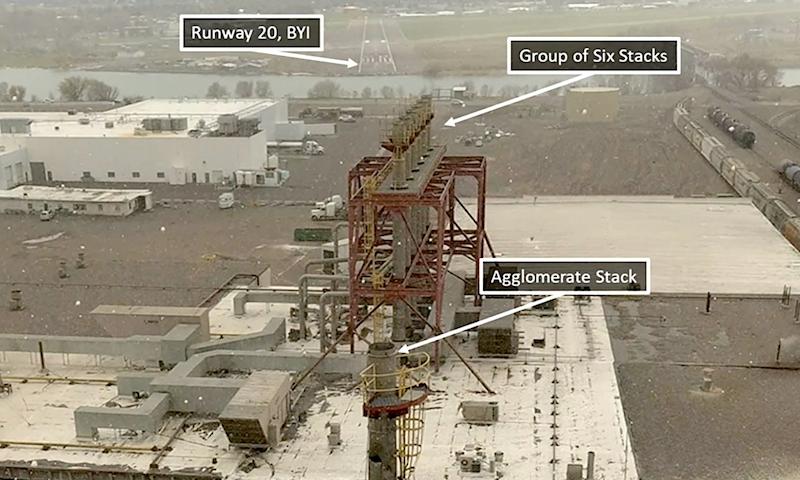

The Burley, Idaho (BYI), Runway 20 final approach showing smokestacks at the centerline.

Now that the FAA has adopted a new rule requiring Parts 135 and 91.147 (air tour) operators to adopt safety management systems (SMS), owners, managers and pilots in those companies will be trying to figure out how the system will help them run a better, safer operation.

They will be asking if the added cost and administrative burden is justified, and they will be looking for some concrete examples of success.

Most, if not all, of these companies already have some type of safety concept imbedded in their flight operations manuals or other policy documents. Some of them already have some type of safety reporting system and many have risk management tools of some kind. Many will be asking: What do I get with SMS that I do not already have?

The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) recently released a final report on a fatal Part 135 accident that provides a way to think about this. We can look at what happened—or did not happen—at the operator before the accident and compare it to what might have happened if an SMS had been in place. The comparison is hypothetical, and there are several possible outcomes, so the analysis is not definitive. But I think it is a useful exercise.

Smokestack On Centerline

On April 13, 2022, the pilot of a Cessna 208B struck a 100-ft.-high smokestack that was only 2,327 ft. from the actual runway threshold at Burley, Idaho (BYI). The stack, one of seven at a potato processing plant, was located right on the runway centerline. The other six stacks were even closer to the runway.

The accident pilot worked for Gem Air LLC, a Part 135 on-demand charter company that also had a UPS freight contract. Based in Salmon, Idaho, Gem Air had been in business since 1982 and flew to BYI regularly. Gem Air did not have an SMS or flight data monitoring program, but it did have a safety reporting system that consisted of safety program drop-boxes and an online portal. The chief pilot said the system was voluntary and non-punitive. The flight operations manual said the safety program was an “institutionalized system for involving all personnel in continuous hazard identification, analysis, prevention strategy, implementation, communications and monitoring.”

In the 11 years since the potato plant was built, Gem Air had not taken specific action on the obstacles at Burley. There was no indication of the stacks on the area navigation (RNAV) GPS Runway 20 approach plate. There was one word, “stack,” buried in the BYI information in the Airfield Facilities Directory. The airport had no tower, and there was no instrument approach to the other runway, Runway 24. In visual conditions you could see the stacks, but in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), you could not see them until you broke out.

Minimums for the straight-in approach were 500-1.

Furthermore, the FAA forced the airport to remove the 3.0-deg. visual approach slope indicator (VASI) lights from Runway 20, but did not require a new 3.75-deg. VASI or precision approach path indicator (PAPI) to replace it. In 2018, the FAA told the plant to paint the stacks orange and white, but the plant did not do it.

The biggest hazard on the approach did not come out until the NTSB interviewed the chief pilot and two company Caravan pilots. Steam clouds from the stacks could obscure a pilot’s view of the runway after they had passed the minimum descent altitude, they said. This was especially true in cold weather and when the wind was blowing right down the runway, as it was when the accident happened.

A pilot who had the most Caravan experience of all the pilots at the company said, “I do normally tell every pilot who's ever joined that if Burley is ever at minimum or just above minimum, not to bother because of that smoke.” He knew from experience that the steam would prevent a safe landing, and his policy was to divert without attempting to land.

That pilot’s experience never translated into effective action. Effective action would have been to cancel the Runway 20 RNAV/GPS procedure. If the only time the instrument approach was dangerous was in IMC, why have the approach at all? Burley had another runway of almost the same length, Runway 24. Repaved and painted and with its own RNAV/GPS approach, it could have replaced the Runway 20 procedure and done so without the obstacles.

Accident Prevention?

So how could an FAA-accepted SMS at the company have prevented the accident?

In an SMS as imagined by the FAA, the pilots who knew about the steam hazard at Burley and the dangers of the approach would have kept talking about it until the problem was resolved. The FAA and the pilot group would have expected the company to change policy and training in a way that would remove or bypass the hazard. They could have stopped using the Runway 20 approach and told the FAA and the airport why. They could have asked the Burley airport manager and city council to make Runway 24 the instrument runway. This active advocacy might even have moved Burley to do something they talked about for years: build a new airport.

All of this could have happened. What happened instead was the experienced pilots at the company kept their insights mostly to themselves and everyone waited for the FAA to come in and solve the problem.

An SMS operator cannot just say they have red drop-boxes or online portals for safety reports and let it go. They have to analyze reports, assess the risks and take actions to control them. They have partners—the FAA and the pilot group—and these two are part of assuring that the company is following up on every report. Operators have to actively encourage reporting and take aim at risk-taking, including their own.

This is not going to be easy. It may not work as well at Part 135 and 91.147 operators as it did at the big airlines. It will be important to track the before and after accident rates to see if all this added process results in fewer accidents. The NTSB or the FAA should do this.