“Horses for courses,” says the old adage, implying that certain things are designed to fill certain roles. A role, however, need not be too narrowly defined, it might actually involve having the ability to be flexible.

Crossover narrowbody jets such as the Embraer E-Jet families and the Airbus A220 family are proving to have the right characteristics to deliver flexibility. Although mainly operating with either regional or legacy carriers, their attributes make them viable candidates to play a major role with low-fare airlines, overcoming the long-time strategy of such carriers sticking to a single fleet type.

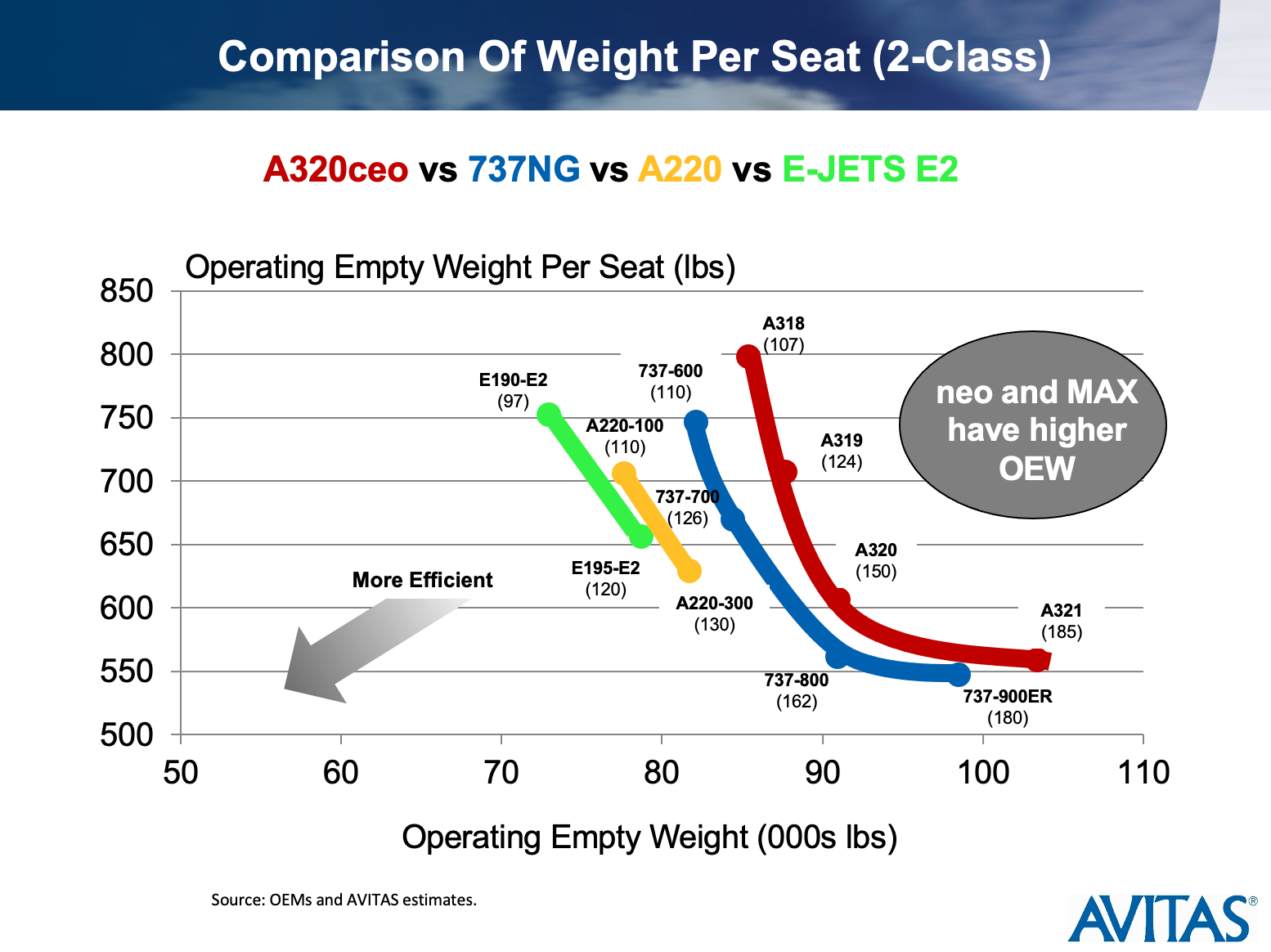

Doug Kelly, senior vice-president – asset valuation with AVITAS, explains that both the families are purpose-built aircraft for the 100-150 seat market. “This gives them a significant operating cost advantage over the 737-700 and A319 due to their lower empty weight per seat and fuel burn efficiency,” he says.

“While the E-Jets have the lowest weight per seat and lower cash operating cost, the A220-100 and -300 enjoy a significant range advantage. The E190-E2 (97 seats) can fly 2,850 nautical miles compared to the A220-100 (110 seats) at 3,450 nm. The E195-E2 (120 seats) can fly 2,600 nm while the A220-300 (130 seats) can fly 3,400 nm. The E-Jets are better suited for shorter-haul operations while the A220s have the flexibility to fly ranges similar to the 737-700 and A319,” he comments.

“The single fleet type has operational flexibility and cost advantages that are difficult to overcome. The airline will require fewer crew and technicians and less parts and it will be much easier to train employees with only one aircraft type. This can save millions of dollars,” Kelly adds. “Airlines need to weigh the performance, operational, and economic benefits to see if adding a second fleet type makes sense.”

Weight advantage per seat of the E-Jets and A220 family compared with the 737NG and A320 family.

Angus von Schoenberg, industry officer at specialist regional aircraft lessor, TrueNoord Regional Aircraft Leasing, notes that not all LCCs opt for the largest capacity narrowbody aircraft. “For example, Southwest is the principal Boeing 737-700 operator, and easyJet built its fleet with the A319. Crossover jets get close to the capacity of those types,” he remarks.

“The E2 and A220 have much lower trip costs than A319/737-700 and slightly better seat mile costs. On a per seat basis, they are competitive with the 737 MAX 8 and the A320neo. Some years ago, AirAsia studied the A220 (then the Bombardier C Series). JetBlue and Breeze Airlines have already chosen to fly the A220,” von Schoenberg continues. “In addition, if the mooted A220-500 stretch becomes reality, the depth of the family’s capacity could have great appeal to LCCs, whereas the E-Jet fuselage cross section does not lend itself to an equivalent growth.”

Patrick Edmond, managing director of Altair Advisory, observes that low-fare airlines tend to focus on per-seat costs. “They want to see low CASKs as part of their low cost base. That has often tended to mean not only packing more seats in, but going for stretch variants of aircraft. In markets with high unmet demand, or where these airlines have faced only legacy competition, they’ve been able to achieve high load factors (and gratifyingly low costs). You could say that in many cases it’s been the “Field of Dreams” school of network planning: ‘If you build it, they will come’.

“The world is changing, though, with COVID-19 as one major impetus,” he notes. “Retrenching legacy carriers may open up more opportunities for LCCs, but at the same time overall demand (especially business demand) is likely to be lower for several years. Many LCCs have already been making inroads into primary airports and business-oriented routes, but meeting business demand means providing attractive frequencies, and in many cases, the ‘classic’ LCC workhorses such as 737-800s or A320s may simply be too large.

“LCCs have by and large not had too much difficulty resisting the temptation of operating smaller aircraft with appreciably higher per-seat costs. But the latest crop of crossover narrowbodies changes the equation,” Edmond reports. “When new technology succeeds in delivering CASKs that are in the same ballpark as larger aircraft, one of the main arguments against a multi-type fleet disappears. The other main argument – the commonality benefits of a single-type fleet – is a decidedly double-edged sword. If you have firmly hitched your airline’s fleet strategy to a single OEM, you’re also giving away your negotiating leverage.

“JetBlue has long had a two-type fleet (and arguably a more premium product which can accommodate higher seat costs) but even it is now replacing its Embraer 190s with A220s. While JetBlue stated publicly that the 2018 contest between the E2 and the A220 was ‘incredibly close’, for Embraer to lose an existing major customer was perhaps an indication that the E-Jets and the A220 are playing in adjacent, but different, divisions,” he opines.

Assessing the market features which might provide the external pressure for low-fare airlines to consider a second fleet type, Doug Kelly believes there is a variety of factors, some echoing points made by Edmond. “Airlines may have concerns about reliance on a single aircraft or engine program. The grounding of the 737 MAX fleet and various problems faced by Boeing, Airbus and the engine manufacturers have made some airlines wary of being too dependent on one manufacturer. A second fleet type may provide confidence that some level of deliveries will occur if problems do arise. There is also the benefit of having the two OEMs battle it out over pricing during fleet purchase campaigns,” he points out.

“Environmental issues may also be a key factor when considering adding a new fleet type. Many governments added environmental mandates as a condition of assistance during the COVID pandemic. To achieve environmental goals, the E-Jets and A220 may be added to fleets or replace older technology aircraft since they can lower carbon emissions by up to 25%,” Kelly states.

TrueNoord’s von Schoenberg agrees. “In consideration of environmental pressures, the A220 and E2 have the best trip footprints available today. LCCs will need to comply with the emissions agenda in their determination of suitable fleet candidates, as much as any other business model,” he says. “However, for many pure LCC or ULCC business models a single fleet type is likely to remain important and many will prefer to change their network rather than their fleet composition.”

While some airlines may see the benefits of changing the make-up of their fleet, it needs to be worthwhile, so the number of crossover jets introduced needs to deliver the right economies of scale. “The advantages of an LCC lie in the asset utilisation and staff hours rather than the fleet size. To benefit from economies of scale in fleet size terms, the same rules apply for LCCs and network carriers alike. From 25 aircraft upwards, the economies of scale flatten out,” von Schoenberg comments.

Edmond favours a similar figure to make a second type make sense. “I would look to around 20 aircraft as a minimum efficient scale for a sub-fleet. When you consider spares pool requirements, the heavy maintenance pipeline starting with the first C checks (especially if done in-house), the cost of a simulator, and so on, I believe the overhead cost per aircraft curve will only start levelling out conspicuously at around 20 aircraft,” he says.

Kelly suggests that for the large low-fare airlines such as Southwest, Ryanair and easyJet, the minimum size for the second fleet type would be around 50 aircraft. “That’s with the expectation to grow much larger,” he remarks. “However, many small airlines may find it possible to switch to a single fleet type with a lesser number of aircraft. airBaltic’s original A220-300 order was for 20 aircraft back in 2016. That initial order has now grown to 65.”

Kelly’s argument begs the question of what potential there is for more carriers to follow airBaltic as a single-fleet type, low-fare airline where that fleet is composed of crossover narrowbody jets? “There might be 30-40 potential carriers to follow airBaltic, but it is more likely to be only a few that actually go through with the change,” he responds. “Any airline that is flying multiple aircraft types that do not carry enough traffic to justify the larger A320/A321 or 737-800/900ER aircraft is a potential candidate. Another reason to switch to crossover jets is to replace older, out-of-production types such as MD-80s, 717s, BAe 146s or F100s.”

von Schoenberg also sees the possibilities for this type of carrier. “There is potential, an example being Breeze,” he confirms. “Also, many mainline carriers are increasingly moving towards offering an unbundled LCC type of product, but often their cost base cannot compare to the most competitive LCC levels of Southwest, Ryanair or Wizz for example. The more crossover types that can be integrated into the lower-cost parts of their operations the better, because this will bring down costs.”

The TrueNoord executive cites JetBlue as an example, particularly with the airline deepening this approach by replacing its E190s with A220s to enhance fleet flexibility.

“The airBaltic model is a visionary one, and it’s enabled by the versatility and the cost-competitiveness of the A220,” declares Edmond. “I think we will see more carriers go down this road.”

He too points to the soon-to-launch Breeze as an example and concludes by offering further reasoning for airlines to adopt this model. “In a competitive marketplace, there can be an advantage to having different (and arguably sharper!) tools in your toolbox compared to your competitors.”