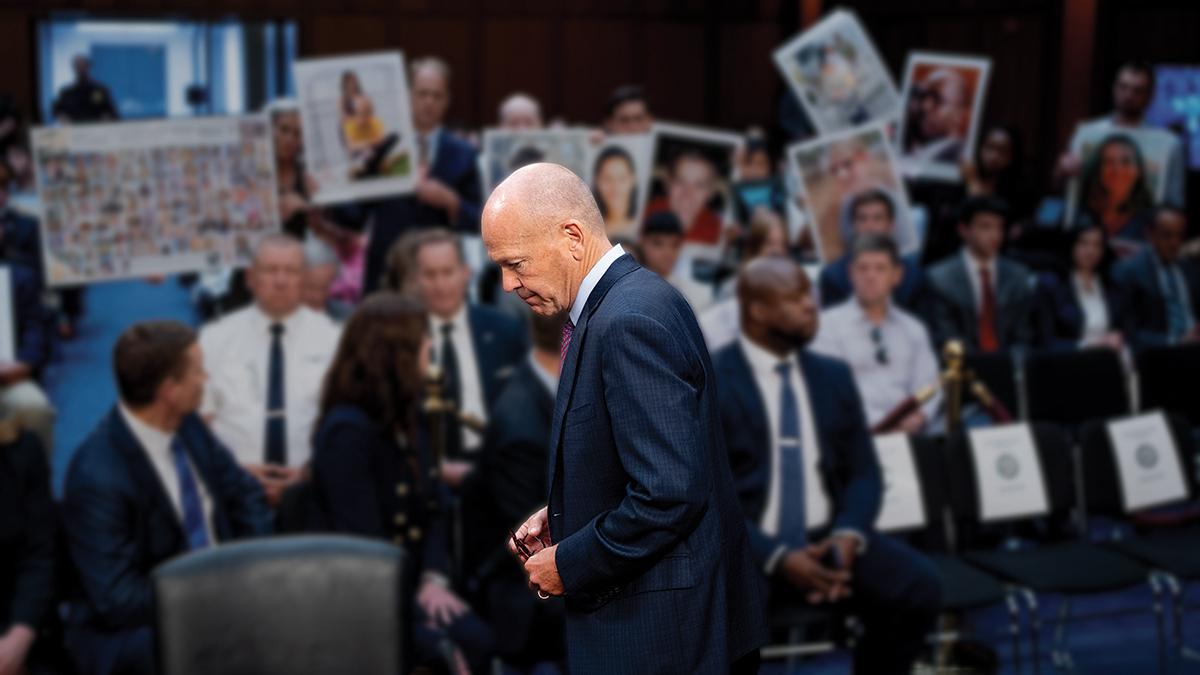

Boeing CEO David Calhoun

When the COVID-19 pandemic shut down the world four years ago, I figured Aviation Week’s annual sit-down with the CEO of Boeing would go the way of that year’s Farnborough Airshow. David Calhoun had other thoughts. Not only did the company’s then-new CEO agree to the interview, but he wanted to meet in person. And so my colleague Sean Broderick and I found ourselves engaged in a lively and candid back and forth with Calhoun in July 2020 across a very large conference table. Later, the three of us took a stroll through Boeing’s eerily empty offices near the Pentagon (now the company’s corporate headquarters).

As we ready for this year’s Farnborough show, the COVID crisis seems a distant memory, but Boeing remains mired in a self-made crisis. I won’t rehash the litany of challenges the company faces—our writers have done a commendable job reporting on them—but it is a long list that involves business, workforce and cultural problems in commercial aviation, space and defense.

Calhoun has announced that he will step down as CEO once a successor is found. So it was disappointing, but understandable, when Boeing said he would not be available after all for an interview we had been scheduling to appear in this issue of Aviation Week. Thus ends a tradition that had endured through good times and bad. Our annual pre-air-show sit-down with Boeing’s top leader dates back 18 years, to Jim McNerney’s first year as CEO.

I will miss interviewing Calhoun. McNerney and his successor, Dennis Muilenburg, rarely strayed far from the corporate script. But one never knew what was going to come out of Calhoun’s mouth, to the delight of interviewers and the dismay of Boeing’s PR team. Two years ago, he stunned us by casually threatening to drop the 737-10, the largest MAX variant, if the U.S. Congress didn’t extend a waiver that made the airplane easier to certify. Boeing prevailed, but other issues have kept the -10 from entering service.

In recent years, as Airbus grabbed a commanding lead in the narrowbody market while Boeing remained fixated on generating cash flow, pressure has mounted for the company to do something to restore parity in the aviation duopoly. Criticism of Calhoun’s inaction has been withering and often personal. Yet he did not seem afraid to face the fire.

In our interview last summer and on an accompanying Check 6 podcast, he doubled down on the likelihood that Boeing might not roll out a new passenger jet before 2035—nearly 25 years after the company’s last clean-sheet aircraft, the 787, entered service. “The notion that we should be looking at niche opportunities or competitive dynamics—when you’re going to invest tens of billions of dollars in a program for 50 years—is just silly,” he maintained. His claim in March that development of a new airplane would cost $50 billion was met with widespread derision.

Yet it would be foolish to think that a new CEO can come in, flip a switch and “fix” Boeing. The company’s decline from an American industrial jewel to a punch line for comedians was decades in the making and not always obvious. We in the media lament that Boeing switched its priority from inventing cutting-edge airplanes to keeping Wall Street happy. But in prior decades, did we do enough to call out that shift as it got underway?

The aerospace industry—suppliers, workers, airlines, investors and even Airbus—should be rooting for Boeing to heal because it’s in their interest. “The aviation industry needs a robust, responsible Boeing,” I wrote shortly after Muilenburg’s resignation in the wake of two 737 MAX crashes that claimed 346 lives. “It needs a vibrant, reliable competitor to Airbus and safe and sustainable new aircraft.” That has not changed.

It will be up to Boeing’s uninspiring board and Calhoun’s successor to restore the company’s tattered credibility. So we look forward to next year’s Paris Air Show, when he or she will hopefully reestablish the longstanding tradition of our CEO interview, and we can hear about the progress that Boeing is making to recapture its former glory.

Comments

Then, top military, aerospace, and high-tech executives need to be recruited (or drafted) at equitable compensation for periods ranging from one to seven years.

These individuals would report to an oversight board (located in the Department of Commerce) to technically manage the Boeing enterprise back into competitive health.