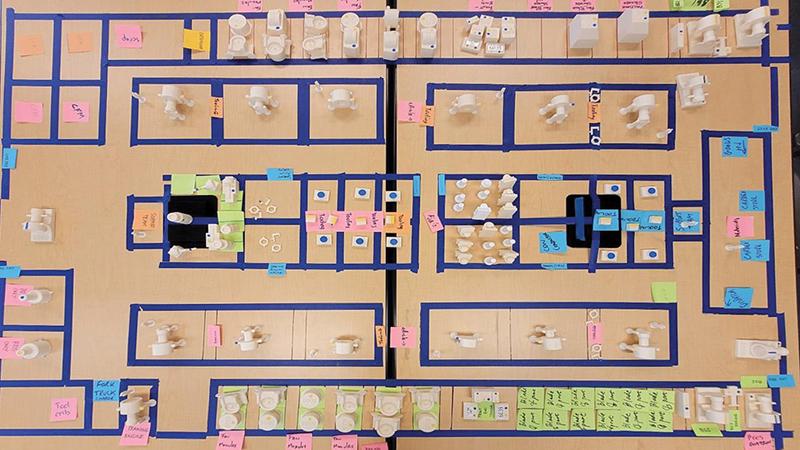

A 3D model representing the standard shop floor concept was used at the June 2023 Kaizen workshop in Cincinnati to help visualize improvements during lean-out improvement efforts.

Credit: GE Aerospace

GE Aerospace Chairman and CEO Larry Culp likes the problems he has these days. He is betting that his suppliers and investors will like the solutions, too. GE’s 2024 fourth-quarter and full-year financial results beat Wall Street’s expectations, and the year-old stand-alone company provided an...

Fixing The Supply Chain Is A Wrenching Experience At GE Aerospace is part of our Aviation Week & Space Technology - Inside MRO and AWIN subscriptions.

Subscribe now to read this content, plus receive full coverage of what's next in technology from the experts trusted by the commercial aircraft MRO community.

Already a subscriber to AWST or an AWIN customer? Log in with your existing email and password.