The number of FAR Part 135 accidents of both fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters in recent years prompted the NTSB to put “Improve the Safety of Part 135 Aircraft Flight Operations” on its 2019-20 Most Wanted List. Some of you who fly business and commercial aircraft may be wondering why. If you just look at the Part 135 accident rate in the year 2000, 2.036 per 100,000 flight hours, and compare it to the 2019 rate, 0.903, the overall accident rate fell by 55%. Isn’t that good? It is, but it depends on how you view the data. Let’s take a look.

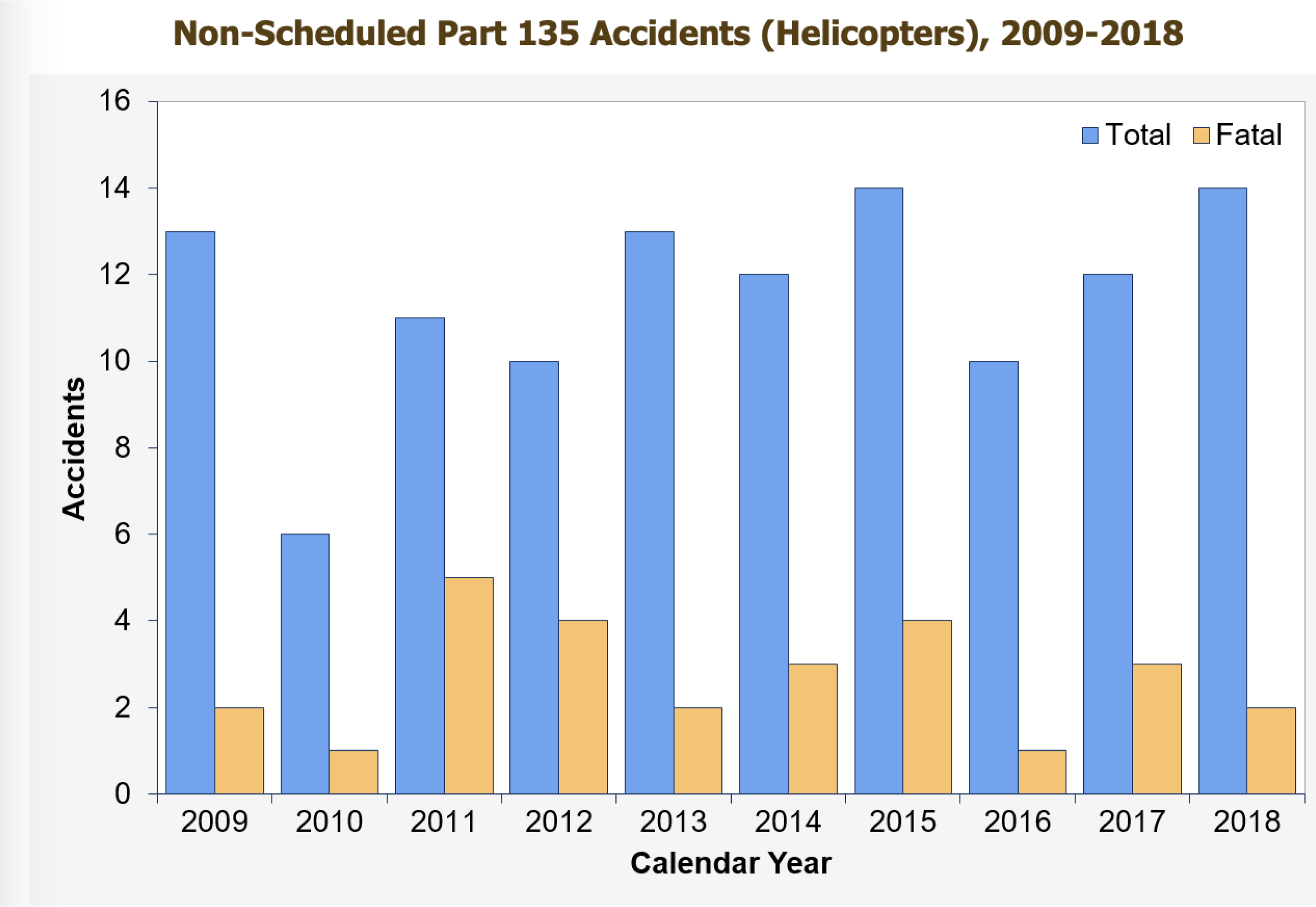

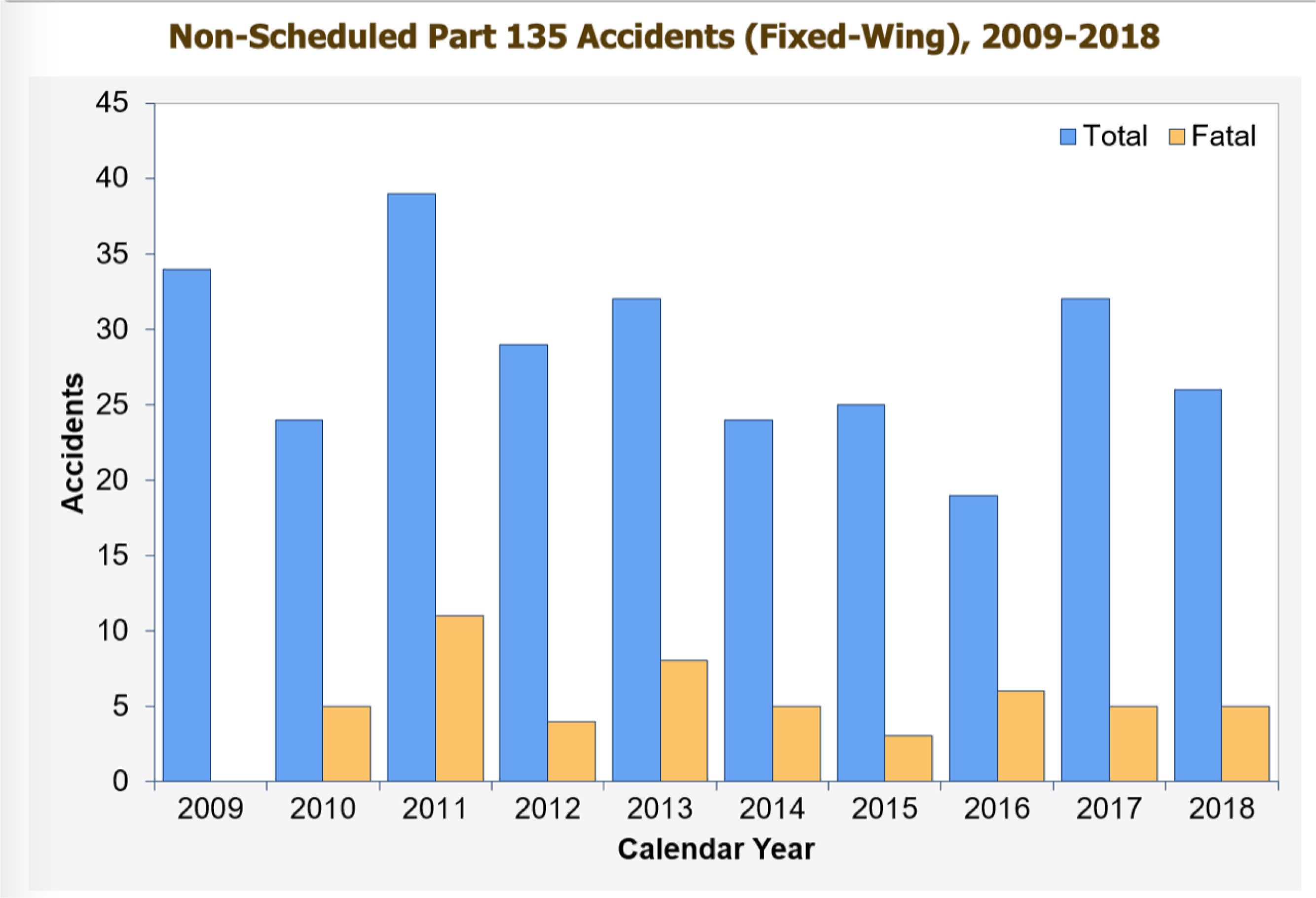

Unlike Part 121 (airline) and Part 91 (general aviation) rates, on-demand Part 135 accident rates have followed a sawtooth pattern from one year to the next. They vary from a high of 2.494 in 2003 to a low of 0.903 in 2019, with a high degree of variance and generally sideways progression. Breaking out meaningful comparisons is tough. Part 135 incorporates a large and disparate group of operations. The NTSB divides the category into commuter, on-demand, fixed wing and helicopter, and sorting through the database to find clear trends can make you a little cross-eyed after a while. One thing, however, seems clear. As a group, Part 135 operators are not closing the safety gap with their airline brethren.

In 2019, U.S. scheduled airlines experienced 36 accidents spread across over 19 million flight hours, resulting in a 0.188 accident rate. Most of the accidents were fairly benign; there was only one fatality. On-demand Part 135 operators experienced almost the same number of accidents, 34, but spread over a bit less than 3.8 million flight hours, putting the accident rate at 0.903. That’s not bad, but it’s almost five times worse than the airlines. Moreover, our on-demand operators suffered 32 fatalities despite much lower passenger loads.

Is it a fair comparison? Of course not. Seven of the fatal Part 135 accidents in 2019 were in helicopters, four were in Alaska, two were in Hawaii, and two were servicing oil platforms. There’s more hazard in some Part 135 operations and fewer flight hours in the accident rate denominator, so you expect a worse rate than the airlines. But here’s the thing: Safety standards are changing.

The tools that have been developed at airlines and at a few business operators have matured, and they work. Terrain awareness warning systems (TAWS), flight data monitoring (FDM), safety reporting systems and the overall organization of safety programs embodied in safety management systems (SMS) have arrived. The risk-taking actions that used to be considered normal--you’ve all heard the pejorative terms for it--in remote locations or marginal weather are now up for scrutiny and are increasingly unacceptable.

The investigation of the Jan. 26, 2020 Island Express (Kobe Bryant) helicopter crash highlighted a sober fact. The accident pilot continued VFR flight into IMC conditions and quickly lost control of the helicopter. According to statements made by NTSB members at a public board meeting in February, helicopter Part 135 operators average about two fatal unintended flight into IMC conditions (UIMC) type accidents every year, year after year. As Vice Chairman Bruce Landsberg said, “We know how these accidents happen, and why, and what we need to do about them.” But they keep happening.

The actions of the Island Express pilot illustrate a troubling mindset that often shows up in Part 135 accidents. Despite policy, training, autopilots and experience, pilots decide to take an unacceptable risk, and it bites them. Furthermore, management give the new safety tools a try, but avoid the harder commitments that can make all the difference. Island Express had a voluntary SMS program, but the company wasn’t certified for IFR operations. Their Sikorsky S-76 had an autopilot, but the pilot, who was IFR qualified, didn’t use it. The training program included a VFR into IMC emergency procedure the pilot practiced, but he didn’t use it when the chips were down.

The NTSB has 19 open recommendations pertaining to improving the safety of Part 135 operations. I’ll be discussing some of these in future articles. I look forward to your comments.

Editor's Note: This is a new BCA safety column called The Crosscheck by Roger Cox that explores the interaction between regulators/investigators and pilots/operators. Send comments to [email protected].