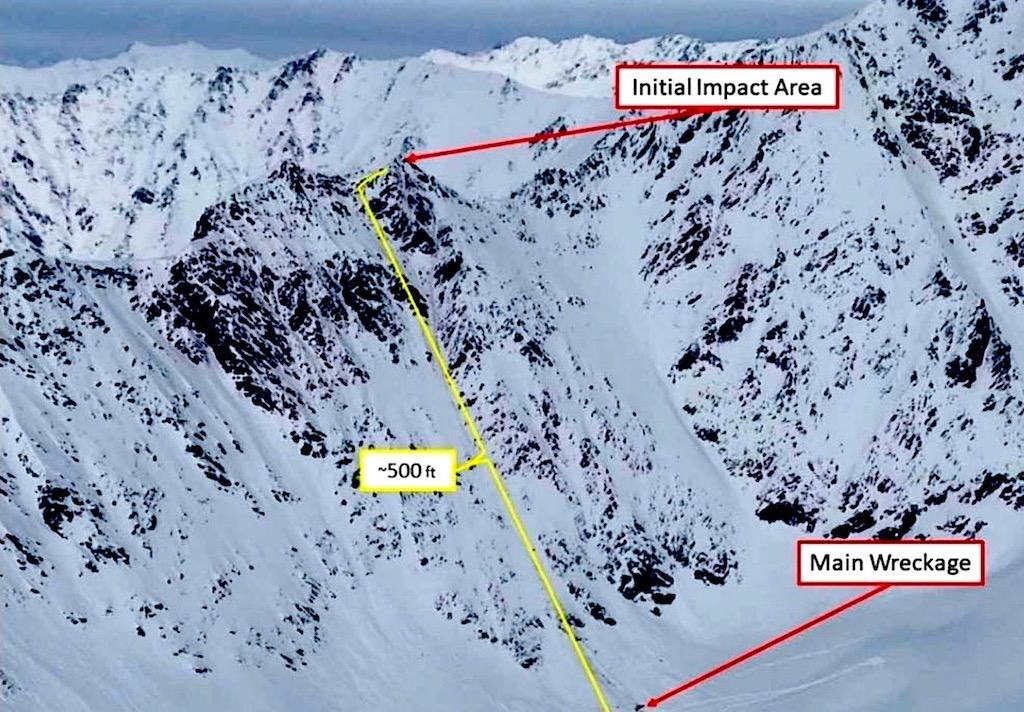

An illustration of the March 2021 collision with terrain of a heli-skiing helicopter, which then slid down the mountainside.

Heli-ski operators take skiers to snowy mountaintops so they can ski down areas of fresh snow in places where most others cannot go. For the customers, it is fun, but for the pilots and the guides, it is also risky. Many things can go wrong. A lot did go wrong on a heli-ski flight that took place on March 27, 2021, near Palmer, Alaska.

That day, an Airbus AS-350B3 pilot attempted to land on a ridgeline in the Chugach Mountains east of Anchorage. Snow was blowing up from the surface, and visibility was falling. The helicopter struck rocks and began sliding backward, down the mountainside. It eventually fell 500 ft. before coming to a stop. The pilot and four passengers died, and one passenger survived.

From the time the helicopter crashed at 18:35 Alaska Standard Time, until the time the surviving passenger was extricated from the wreckage and began the flight to the hospital, 6 hr. 40 min. had passed.

When investigators arrived, they pursued several safety-related issues, but two stood out. Why did the pilot not execute an escape maneuver, and why did it take so long for the survivor to be rescued?

Soloy Helicopters of Wasilla, Alaska, operated the helicopter as a 14 CFR Part 135 flight. It was under contract to Tordrillo Mountain Lodge, which employed the guides and provided hospitality to the skiers. The division of responsibilities between these two companies became an issue for the NTSB.

The helicopter took off from its base at Wasilla Airport (PAWS) at 14:40. It took about 10 min. to fly to a residence by Wasilla Lake, where it landed to pick up its passengers. Two guides and three skiers boarded, and the helicopter took off again, this time headed for the Chugach Mountains to find good ski runs. A Garmin Aera 660 portable GPS on board recorded the aircraft’s movements.

From 16:12 to 18:07, the helicopter made numerous drop-offs and pickups of the skiers in the mountains east of Wasilla. At 18:27, it took off and began a climb to 5,900 ft. while tracking along a rising ridgeline. At 18:33, it began maneuvering at slow speed only 14 ft. above terrain that was at 6,266 ft.

The pilot attempted to land on the ridgeline, but pulled up before making a second attempt. The helicopter became engulfed in fog and snow, and someone called out, “no, no, don’t do it.” The helicopter began “going backward real fast” and rolled backward down the mountain.

The GPS stopped recording data at 1836:42. It was then near the final resting point of the main wreckage. When responders later viewed the accident site from the air, it was evident the helicopter struck rocks about 15-20 ft. below the top of the ridgeline.

Prolonged Response

When the aircraft came to rest, the surviving passenger found himself stuck in snow and lodged between two other passengers and unable to move. He saw the passenger who had been to his right sitting outside in the snow. That passenger spoke to the passenger still inside the aircraft, but eventually he began sliding downhill and stopped responding.

A Tordrillo lodge heli-ski guide who had been monitoring the accident flight with a Garmin InReach satellite communicator attempted to contact the aircraft at 19:04. He notified a supervisor at 19:15 that he had no positive communications with the aircraft. Another experienced guide discussed the situation with the lodge’s co-owner, and they concluded the crew on the flight was “taking their time and enjoying the last run of the day.”

That guide, who was the owner of another heli-ski lodge, began checking on the missing flight. Several helicopters not part of the Soloy/Tordrillo operation were alerted to a possible downed aircraft. More than an hour went by before the lodge owner called Soloy’s director of operations to discuss the situation.

Finally, at 20:30, Tordrillo Mountain Lodge activated its emergency response plan, followed by Soloy at 20:32. However, the Alaska Rescue Coordination Center (AKRCC) did not record being notified until 21:10.

A helicopter from another heli-ski operation first located the wreckage at 21:36. The crew told AKRCC the accident location was on the “Knik (Glacier) side of the ridge.” When an Alaska Air National Guard HH-60 helicopter arrived, it was too heavy to descend in a hover, and the crew needed 30 min. to dump fuel down to a safe weight. Two pararescuers finally arrived on the scene at 00:15. The surviving passenger was still wearing his seatbelt and had to be cut out of his seat. At 01:15 the rescue helicopter departed with the victim and arrived at a hospital in Anchorage at 01:36.

The Investigation

The NTSB’s investigative team included specialists in operations, human performance, airworthiness, weather and survival factors. A lab specialist downloaded the data from the Garmin GPS tablet and created a detailed map of the helicopter’s movements and the sequence of events. The team was assisted by representatives from Airbus Helicopters, Safran Engines, France’s Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety, the FAA and Soloy Helicopters.

Safety investigators interview the surviving passenger, in Part 2 of this series.