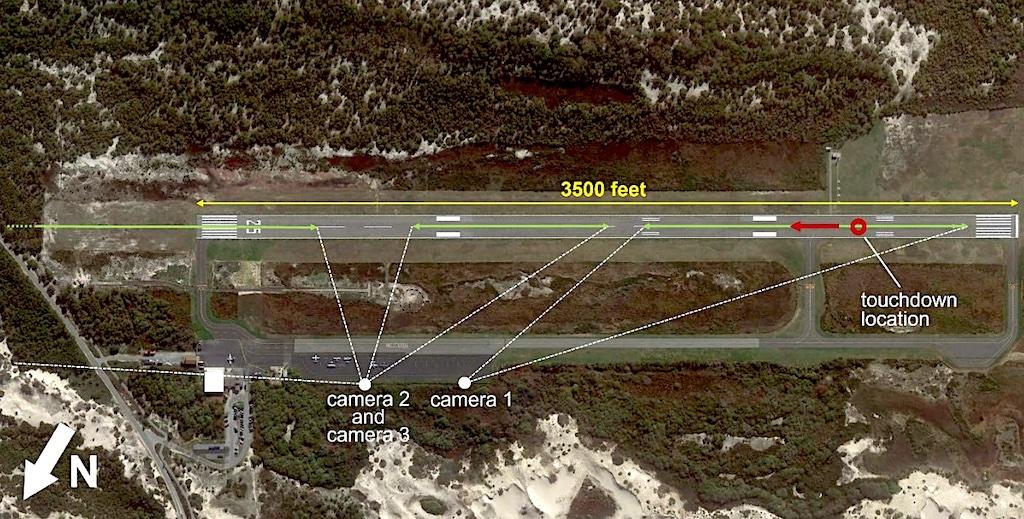

Aerial view of Provincetown Municipal Airport showing camera angles.

NTSB engineers investigating the crash of Cape Air Flight 2072 calculated that if the pilot had maintained the same level of deceleration while remaining on the ground, he would have stopped the airplane somewhere between 68 ft. before the end of the runway and 88 ft. beyond the end of the runway. The Cessna 402C probably would have experienced little or no damage and it is likely there would have been no injuries.

An additional analysis concluded that the accident flight would have cleared the trees if the pilot had maintained its liftoff speed rather than accelerating in an attempt to achieve its best angle of climb speed (Vx). The lowest possible airborne speed was 65 kts., stall speed with flaps 45° and gross weight 6,215 lb. (The flaps were probably retracted, so the realistic minimum speed would have been higher.) The highest speed possible was the speed of the airplane when it collided with trees. That was 84 kts., also Vx.

The investigation found that “N88833 was able to accelerate and take off from Runway 7 with the assistance of ground effect, but as the height above the ground increased and ground effect decreased, the airplane could not maintain both its acceleration and its climb.” If the lift-off airspeed had been maintained (without further acceleration), the airplane should have been able to achieve a flight path angle (𝛾) between 6° and 8°, which would have been sufficient to clear the trees.

The NTSB accident report did not recommend that anyone make a practice of climbing at less than Vx or Vy. As Cape Air noted in draft comments,“it is not common to train crews to climb at speeds below 𝑉x and 𝑉y in twin-engine reciprocating aircraft.”

The flight complied with the minimal requirements of 14 CFR 91.103, “Preflight Action,” in that the pilot was “familiar with all available information,” including the landing runway length and the airplane’s landing distances. No extra safety margin is required by that regulation. Adding a 15% safety margin to the required landing distance for a wet runway and a 5 kts. tailwind would still have allowed the flight to proceed. However, the stopping margin would have been less.

The 15% safety margin is recommended by the FAA in Safety Alert for Operators (SAFO) 19001, “Landing Performance Assessments at Time of Arrival.”

Conclusions and Comments

The NTSB found the probable cause of the accident was: “the pilot’s delayed decision to perform an aborted landing late in the landing roll with insufficient runway remaining. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s failure to execute a go-around once the approach became unstabilized, per the operator’s procedures.”

The pilot bore full responsibility for the accident. However, his employer could have minimized the risk of his ill-considered go-around by implementing a commit-to-stop policy. To its credit, Cape Air did implement a policy after the accident. In a letter to the NTSB in 2023, the company described its new policies.

One of those new policies is: “Once the airplane has landed, the aircraft is committed to stopping, and a go-around will not be attempted.”

FAA Information for Operators (InFO) 17009 provided the agency’s reasoning for a commit-to-stop policy. It was based on NTSB Safety Recommendations A-11-18 and A-11-19. While the NTSB wanted to see commit-to-stop incorporated in airplane flight manuals, the FAA said, “operational factors are too numerous and varied to establish a single committed-to-stop point.

The FAA believes operators are in the best position to make this determination for their operation and type aircraft. Operators who establish committed-to-stop points would eliminate ambiguity for pilots making decisions during time-critical events.”

The commit-to-stop guidance was aging but still valid. A Hawker accident that took place in 2008 and FAA guidance encouraging commit-to-stop was issued in 2017. InFO 17009 had been in effect for four years at the time of the Cape Air accident, and it was one of 21 InFOs issued by the FAA in 2017. If you weren’t aware it was there, you might have trouble finding it.

The guidance was directed at turbine operators, so perhaps Cape Air officials didn’t think it applied to the company. Or maybe that hadn’t seen it. During investigations, I sometimes asked chief pilots and safety managers if they read InFOs and Safety Alert For Operators (SAFO). Too often, they said, “what’s that?”

Advisory guidance that’s not mandatory tends to be somewhat transient. For operators who read and apply the guidance right after it is issued, the InFO’s safety message can be effective. For those who don’t, increasingly those lessons are lost.

There is a remedy to indifference. The addressees mentioned at the bottom of the InFOs and SAFOs should read them and take them seriously. They don’t have to wait for another accident to re-learn lessons that have already been taught.

Deciding Too Late To Go Around, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/deciding-too-late-go-around-part-1

Deciding Too Late To Go Around, Part 2: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/decidi…;\/p>