The charter industry is a vibrant one, but it faces a number of challenges, such as increased market competition, taxation and tariffs, and talent acquisition and retention, experts said during the first U.S. conference by the Air Charter Association, a London-based not-for-profit organization.

Charter operators and charter brokers have different sorts of challenges, Air Charter Association CEO Glenn Hogben said following a recent day-long conference in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

The industry, and in particular charter brokers, must present themselves as a value proposition.

“What does a broker do for me?” Hogben says. “There’s a huge amount of complexity to arranging charter flights. Things go wrong every single day, and that broker is the professional advisor. They know which operators to use for which trips; they know which aircraft are the right aircraft to use for the trips. It’s quite a complex process of putting that mix together and making sure you’ve got the right aircraft, the right type of operator that will deliver the right service.”

That comes with a cost, he says, but one that pays off.

It is the broker, for example, who takes the call 3 hr. before a flight is scheduled to depart with news the aircraft has a maintenance problem, the catering did not arrive or the crew has timed out on flight hours.

When the customer arrives, those problems have quietly been solved in the background. “Brokers are problem solvers,” Hogben says. “We try and encourage our brokers to make sure the clients know the work they’ve been doing. Because if the client doesn’t appreciate the work you’ve been doing, it’s not demonstrating the value you’re adding.”

There are brokers who focus only on price, however.

“Offering the cheapest aircraft is the only thing they’re interested in,” he says. But, “your client may have a very important meeting at 9:00 that day and that’s why they’re traveling.” And an operator with a small fleet, for example, may not have another aircraft available should something go wrong with the aircraft. Instead, it would be best to advise them to use an operator with a larger fleet so there is a backup option.

“You might be the cheapest option, but it might not be the right option in the event that something goes wrong,” Hogben says.

At the same time, the industry suffers from a lack of regulation.

“You have different levels of broker,” says Joe Fenn, Air Charter Service private jet director for North America. “Anyone can put up a nice website ... The lack of regulation and accountability means that anyone can do it. For us personally as a company, we invest so much in the early training. We work with operators. We invite them in ... You’ve got to have the relationship both on the client side and on the operator side. And understanding exactly what it is that goes into every single trip is so important.”

The Air Charter Association, for example, vets new members before they are allowed to join. It has created a Best Standards Committee, as well. Argus Platinum and Wyvern Wingman are third-party safety and quality ratings for operators. And the Air Charter Safety Foundation’s Industry Audit Standard is a voluntary aviation audit for Part 135 and Part 91 aircraft operators.

Other challenges come from taxation and tariffs, Hogben says.

“Parts of the world are all going through changes,” he says. Many European countries are imposing higher taxes on business aviation to make up budget deficits. In reality, business aviation delivers a lot of value for a country’s economy with many companies supporting it. However, with increasing taxation, some companies have cut back travel, while others have moved elsewhere, which means the country loses all the tax income.

Tariffs have also impacted the industry. Pilatus, for example, has paused deliveries to the U.S. The good news is, however, that many of the tariffs have been reduced or delayed.

At the same time, recruitment and retention of talent is also challenging.

For one, students are not always aware of the opportunities found in the business aviation charter industry, says Ryan Waguespack, a U.S. boardmember with the Air Charter Association. For those who do, a pathway is not always clear.

Waguespack is an advisor at Auburn University, which has a robust aviation program, he says. Students there are interested in private aviation, “but they look at our industry and go, ‘Well, where do I start? How do I grow?’ Because unfortunately, the industry has said, ‘Jump in. The water is deep. I hope you can swim.’”

To help, the Air Charter Association has started outreach to colleges and universities to introduce people to the industry, which is not well known. It also offers internships and training programs, including broker training qualification. And it is developing a new training course as an introduction to aviation for operators, handling agents and others.

At the same time, the charter market has changed since the proliferation of jet cards, fractional ownership and charter services during the pandemic. Today, business has become more normalized.

“Now you’re actually having to sell,” Waguespack tells Aviation Week. “And you’ve got a generation of sales teams that really have never had to [during the busy times of the pandemic]. Now, they’re like, ‘Whoa.’”

Kirti Odedra, director of sales for Planet 9 Prime Air, agrees. Planet 9, based in London with U.S. headquarters in Van Nuys, California, specializes in aircraft management and charter. Her team is working hard to build relationships with brokers to gain their business and their trust. That is important as brokers have a choice of multiple operators with similar pricing.

“I think face-to-face [meetings] are more important right now than ever,” Odedra says. People do business with the people they like.

“As a human being, you’re more likely to call them up and ask for what you need, share your worries, like what might go wrong, and then you’re going to get a response from them,” she says. “You obviously have to back it up with the service and quality.”

At the same time, costs—such as fuel prices and ground handling—have increased.

“When somebody says, ‘Hey, my client paid X amount last year, [but with] inflation, you try to tell them, ‘Hey, it’s going to be $10,000 more,’ and they’re like ‘No. No. No.’ I think that’s up to the broker to educate their customers and try to pass that on. As operators, we can do so much, but it’s up to the brokers out there to educate their customers and steer them in the way that, ‘Hey, you should use this operator for this reason -for reliability. They’re not going to cut corners. They’re not operating an aircraft in the gray [or illegal] market.’”

There are 1,978 Part 135 air carriers in the U.S., Waguespack says. “We’re in a cottage industry.” And education is key.

All the details, from the large to the tiny ones, must be addressed. “There’s so many layers in this business,” Odedra says. “It takes a village.”

Most recently, there has been a new generation of customers who are more price driven in a shift from corporate trips following the pandemic to leisure ones.

As an operator of ultra-long-range aircraft, “we haven’t seen as much flying from investment banks, the larger corporates—where they were doing site visits, where they were doing tours around Europe for two days visiting all of their offices,” Odedra says.

The majority of transatlantic flying today is for leisure, she says.

“And when people are spending their own money, they are going to be more cost conscious, whereas if it’s a corporate flight, they’re going to go with the more reliable option,” Odedra says.

Corporate customers ask more questions about standards, certifications and pilot training. “I don’t think that even comes into conversation when we’re flying a lot of leisure passengers,” she says.

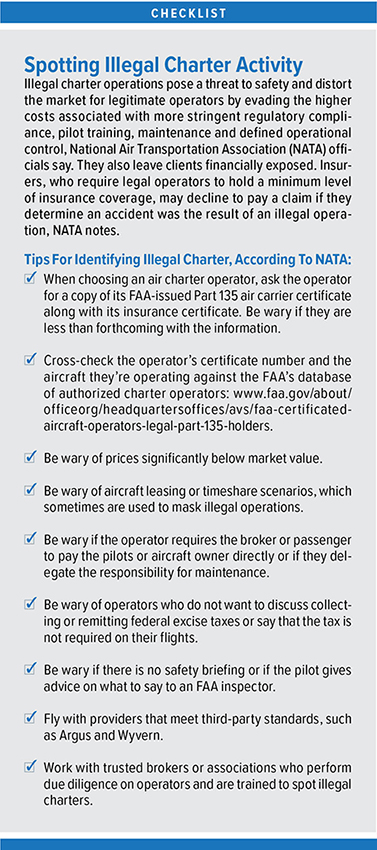

Another challenge is the proliferation of illegal charter operations with Part 91 operators with private aircraft performing Part 135 flights for hire.

“They’re not all necessarily intentional,” Hogben says. But as soon as they take money in return for a flight, whether it’s from a friend or a friend of a friend, the flight immediately turns into a commercial operation. “That makes it illegal.”

That also puts passengers at risk. The aircraft may not have had the required maintenance and pilots may not have had the proper training or follow adequate safety protocols.

At the same time, should there be an accident, the operator’s insurance becomes invalidated as the insurance required for a commercial flight is more stringent, he says.