CAPA Perspective: Aviation’s Sustainability Question

A Boeing 777 climbs away from a snowy runway.

More than a decade ago, the aviation sector set a series of lofty goals around aviation sustainability: improve fuel efficiency by 1.5% per annum; cap net CO2 emissions from 2020; and reduce net CO2 emissions by 50% relative to 2005 levels by 2050. IATA member airlines doubled down on their sustainability ambitions with the Fly Net-Zero Commitment agreed to in 2021.

Progress has been slow, and the industry can only now start to point to measurable steps on sustainability and meeting its goals. The transition away from conventional aviation fuel and towards sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) is where the majority of the industry’s efforts are concentrated.

Despite SAF being the main game for airline sustainability, it remains both scarce and expensive. IATA estimates that global SAF production will roughly triple in 2024, but even this will only meet around 0.5% of airline industry fuel consumption.

SAF prices are variable, dependent on the feedstock and technology used to produce the fuel, but are generally anywhere from two to four times that of conventional jet fuel. In a sector where profit margins are slim at best, doubling or quadrupling the cost of one of the main inputs would seem make questionable business sense. Yet, airlines are going to consume every drop of SAF that is available to them.

With SAF so difficult to obtain and costly to use, the transition away from conventional fossil fuels is being led by large, commercially successful airlines. These carriers have the financial resources to absorb the cost and the scale of demand required to secure large amounts of the current supply and future pipelines of available SAF.

Unfortunately, this is leaving smaller carriers stranded without access to SAF and unable to join the industry transition. The answer to this problem is to create certainty: airlines need to know that SAF supplies will be there for them, and producers need to know that the demand will be there for their output.

For the moment, this certainty is sorely lacking. With a few exceptions, governments have yet to put in place the sort of regulatory frameworks and policies that will support the aviation sector’s decarbonization ambitions. The private sector is leading the way but can only go so far until the public sector gets its policy and regulatory settings in place.

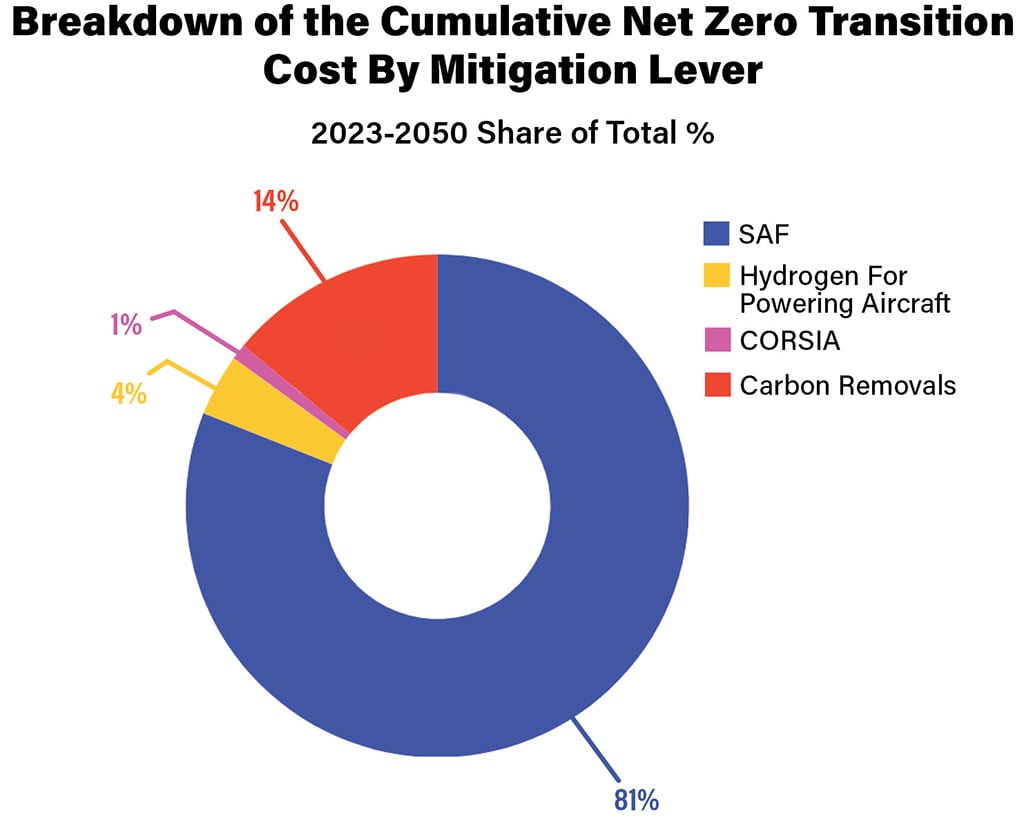

There have been increasing questions about whether the industry will hit its targets. IATA revealed in its updated Policy and Finance Net Zero Roadmaps, which contain expanded and deepened analyses on sustainability, that the air transport industry’s energy transition is feasible on the 2050 horizon.

However, the success in the transition depends critically upon policymakers’ unity of purpose, with the time left for joining forces in air transportation’s energy transition shrinking by the minute.

IATA research indicates that the amounts of investments needed to make the energy transition possible are comparable to those engaged in previous creations of new renewable energy markets: manageable but huge.

Governments, airlines and the travelling public want to see the energy transition occur, but it cannot be understated just how difficult, expensive and time-consuming this is going to be.

The industry needs to communicate this to policymakers and the travelling public to ensure that the supporting frameworks are there for the energy transition. Inaction or delay only opens the sector up to increasing risk of having frameworks imposed on it, which could have major consequences for the business of air travel.

New technologies and solutions like hybrid-electric aircraft and hydrogen fuels are potentially decades away, so the industry needs to focus on SAF because it is the best alternative that is available now. To do that requires a collective effort in which governments/regulators set up frameworks and incentivization to ensure maximum participation from stakeholders.