Air-Breathing, High-Speed Propulsion To Make 2021 Comeback

A comeback attempt for the use of missiles powered by scramjets and solid-fuel ramjets will highlight a dizzying year for development and testing of the most advanced long-range weapons.

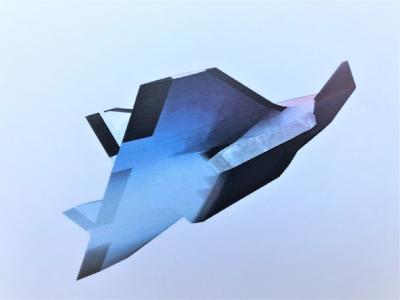

Two versions of DARPA’s Hypersonic Air-Breathing Weapon Concept (HAWC) are set to perform the first powered flights of a scramjet engine since the final flight of the Air Force Research Laboratory’s (AFRL) X-51A Waverider in 2013.

- U.S. Air Force opens three-way competition for scramjet missile contract

- First long-range hypersonic weapon test set in 2021

The planned flight tests of competing HAWC demonstrators designed by Lockheed Martin/Aerojet Rocketdyne and Raytheon/Northrop Grumman teams merely constitute the first step in the Pentagon’s plans to deliver to the field the first operational prototypes of scramjet-powered hypersonic cruise missiles in five years.

The follow-on Hypersonic Air-Breathing Cruise Missile (HACM) program has the goal of establishing a long-term competition among the two HAWC competitors and possibly Boeing. In November, the Joint Hypersonic Transition Office funded Boeing to complete a preliminary design and mature the propulsion system for HyFly 2. The original HyFly experimental program ended disappointingly in 2010 but featured a dual-mode ramjet optimized to fit on the Navy’s weapons elevators aboard aircraft carriers.

Separately, the U.S. Defense Department announced a partnership with the Australian military on Nov. 30 to develop full-size prototypes within five years for another air-breathing hypersonic technology.

Taking inspiration from the 15-year collaboration on the Hypersonic International Flight Research Experimentation (HIFiRE) program, it is possible the Southern Cross Integrated Flight Research Experiment (SCIFiRE) will see continued development of hydrogen-fueled scramjet engines for new hypersonic missiles.

As the Pentagon labors to solve the tyranny of distance and sophisticated air defense, novel concepts that promise the potential of extending the range and speed of future missiles are enjoying support.

Some are racing to enter service within two years. The Air Force’s Lockheed Martin AGM-183A Air-Launched Rapid Response Weapon (ARRW) was set for its first powered flight test in late December. Within the next 12 months, the Army and Navy plan to demonstrate the first Block 1 Common Hypersonic Glide Body (CHGB), along with a prototype of the 34-in.-dia. two-stage rocket stack of the Long-Range Hypersonic Weapon (LRHW). The ARRW and LRHW are due to enter service by fiscal 2023, followed two years later by the Navy’s sea-launched Conventional Prompt Strike missile, which also features the CHGB.

Air-breathing propulsion concepts also are being developed to extend the range of the Army’s artillery projectiles. On Nov. 30, Northrop Grumman announced completion of a round of testing on a solid fuel ramjet, the critical technology for the XM1155 Extended-Range Artillery Projectile.

In Europe, Norway appears to be taking an early lead in high-speed/-hypersonic missile development, building off joint work with the U.S. on the Tactical High-Speed Offensive Ramjet for Extended Range (THOR-ER) Allied Prototyping Initiative demonstration program.

Following the formalization of cooperation with the U.S. Defense Department in November, the THOR-ER team, which includes the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment, state-owned armaments company Nammo and the U.S. Naval Air Warfare Center, is looking to undertake the firing of a ramjet-powered missile from a firing range at Andoya during 2021.

Nammo also is progressing with its proposed ramjet-powered artillery shell, which it unveiled in conjunction with Boeing in 2019. Nammo plans to have the round on the market for 2023-24, ready for use in Norway’s new K9 Vidar self-propelled artillery.

France is following closely behind with hypersonic efforts associated with enhancing its air- and sea-launched deterrent. The first likely to deliver results is the V-MAX Experimental Maneuvering Vehicle, which is expected to undertake a first flight during 2021. ArianeGroup is apparently the lead company for the project.

Secrecy continues to surround developments for the ASN4G, the weapon that is scheduled to replace the nuclear-armed ASMP-A air-launched missile in the deterrent mission beginning in 2035. Budget documents published in October show France is spending €1 billion ($1.2 billion) on modernization of the deterrent with the ASN4G expected to take a substantial chunk of the money.

Officials say they are looking for a balanced improvement on range and speed over the ASMP-A but note the future weapon still will need to be compatible with the Dassault Rafale, which will be the primary carrier aircraft until at least 2040.

France also is leading pan-European efforts with Finland, Italy, Netherlands and Spain to hammer out requirements for a missile-defense capability that could provide intercepts of hypersonic and supersonic cruise missiles under the Timely Warning and Interception with Space-based TheatER (Twister) initiative.

Across the English Channel, decades of hypersonic missile research may be poised to bear fruit. Ongoing studies by the UK Defense Ministry with France to replace the Exocet and Harpoon with a high-speed anti-ship missile by the late-2020s offer an opportunity to consider hypersonic options.

To this end, the UK Defense Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) appears to be gathering technical expertise. A partnership called the Thresher project, which was formed in 2018 with the U.S. AFRL, is conducting experiments through 2022 or 2023 on technologies that can lead to a new hypersonic weapon. Meanwhile, the DSTL also has studied a concept for an air-launched hypersonic glide vehicle, concluding such a project is technically feasible as long as the UK can overcome challenges with sourcing rocket-motor, aerodynamic-control and thermal-protection system technology.

Maritime strike also appears to be driving hypersonic weapons programs in Japan and India, two of China’s principal competitors in Asia.

A Block 1 hypervelocity glide projectile with limited apparent maneuvering capability remains on track to enter service, with a Block 2 follow-on featuring a waverider shape expected to follow in the 2030s.

A visit in July by Japanese Vice Defense Minister Tomohiro Yamamoto to the Advanced Science Research Center (ASRC) outside Tokyo yielded a tweeted photo of a full-scale hyper-sonic cruise missile (HCM). The ASRC has partnered with the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency to develop a dual-mode ramjet. An “early deployment” version of the HCM is scheduled to enter service around 2030. That schedule suggests Japan could begin demonstrating scramjet engines with advanced cooling technology just using a form of jet fuel that doubles as a coolant.

India made great progress toward fielding a hypersonic weapon in 2020. On Sept. 7, an Indian Agni-I missile launched the Hypersonic Technology Demonstration Vehicle (HSTDV). A scramjet developed by India’s Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) activated, propelling the HSTDV for 20 sec. to a maximum speed of Mach 6. The HSTDV remains an indigenously designed alternative to the Brahmos-II, a hypersonic cruise missile in joint development with Russia’s NPO Mashinostroyenia.

One of the more intriguing hypersonic programs is underway in Brazil. For nearly a decade, the Brazilian Air Force has commissioned the Institute of Advanced Studies (IAS) to research a concept for a scramjet engine with the name “14-X,” referencing the original 14-Bis aircraft design of Alberto Santos Dumont.

Orbital Engineering, a Sao Paulo construction firm that delivered the design for the 14-XS demonstrator in January 2019, has begun manufacturing the scramjet engine and airframe. Four flight tests are planned, with the first seeking to demonstrate the scramjet functions at a supersonic speed. A follow-up test of the 14-XSP demonstrator is expected to show air-breathing propulsion at hypersonic speeds. A third test of an unpowered 14-XW vehicle will represent the first experiment with guidance, navigation and control technology. Finally, the fourth test of the 14-XWP vehicle should demonstrate the same technology, with the scramjet engine activated to achieve hypersonic speed.

During the Nov. 13 National Defense Seminar, Brazilian Air Force commander Lt. Brig. Antonio Carlos Moretti said integration of the engine for the 14-XS demonstrator was still underway but provided no update on the schedule for the first flight test. Ultimately, Brazil plans to use the 14-X to launch satellites into orbit, Moretti says.

Comments

During the 2000s and 2010s there was no sense of urgency, run a few test flights and quit for a few years, lather, rinse, repeat. The Air Force and Navy saw no real need for an AAM with a range outside what was possible with AMRAAM.

Who dropped the intelligence ball?