NASA has faced many formidable challenges in a decade-long quest to restore U.S. human orbital spaceflight, so it may have been better prepared than other agencies to face widespread travel bans, workplace shutdowns, health issues and other quagmires posed by the ongoing coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic.

But confident in its ability to complete outstanding work, NASA announced a target launch date of May 27 for a flight test to the International Space Station (ISS) by two U.S. astronauts aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule flying from Florida.

The launch, scheduled for 4:32 p.m. from Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39A, will be the first human orbital space launch from the U.S. since the space shuttle Atlantis touched down at the Florida spaceport on July 21, 2011, closing out the 135th and final space shuttle mission.

The return of Atlantis marked the start of U.S. dependence on Russia to ferry crews to the ISS, a 15-nation orbital laboratory that has been continuously staffed by rotating teams of astronauts and cosmonauts since Nov. 2, 2000.

As the station prepares to mark 20 years of human presence in orbit, NASA is in the homestretch of launching astronauts from U.S. soil—while testing a new business model for human space exploration that it intends to expand for travel to the Moon as well. “We are at the cusp of making our Commercial Crew dreams a reality,” says Douglas Loverro, NASA associate administrator for human exploration and operations.

NASA kicked off its Commercial Crew partnership program in 2010 with the goal of financially and technically supporting private enterprise initiatives to develop human space transportation systems. The idea was that NASA would become one customer among many, buying flight services, similar to how it contracts with SpaceX, Northrop Grumman and Sierra Nevada Corp. for ISS cargo supply runs.

In September 2014, NASA narrowed the field of Commercial Crew contenders to Boeing and SpaceX, awarding the companies $4.2 billion and $2.6 billion, respectively, for flight tests and up to six operational crew-rotation missions. The goal was to have one or both of the companies transport crew to the ISS in 2017, but funding shortfalls and technical issues delayed both programs.

Despite contrasting cultures and a 38% difference in NASA funding, Boeing and SpaceX have been neck and neck in a low-profile race to be the first to launch NASA astronauts.

SpaceX successfully flew an uncrewed Dragon 2 mission to the ISS in March 2019, then lost the capsule during preparations for a static test fire of the launch abort system a month later.

Software problems precluded Boeing’s uncrewed CST-100 Starliner from docking with the ISS during its orbital debut last December, a test that is scheduled to be repeated this fall. Both Boeing and SpaceX have been bedeviled by parachute development and testing.

SpaceX is providing Dragon’s ride to orbit, so Falcon 9 issues have migrated onto NASA’s radar screen as well. For example, NASA announced a launch date for SpaceX’s Demo-2 mission, which will carry astronauts Robert Behnken and Douglas Hurley, only after it was satisfied with SpaceX’s explanation for a March 18 Falcon 9 premature engine shutdown.

Residual cleaning fluid trapped inside a sensor ignited, prompting a cutoff of the Merlin 1D engine toward the end of the first-stage burn, SpaceX disclosed on April 22. The booster’s eight other engines were able to successfully deliver the payload—a sixth batch of 60 SpaceX Starlink satellites—into its intended orbit.

Boeing’s ride to orbit for the Starliner capsule—United Launch Alliance’s Atlas V—has received similar scrutiny, though it has had a longer and smoother ride during its 83-flight history than SpaceX’s Falcon 9. The Falcon 9, which first flew on June 4, 2010, made its 84th flight on April 22, surpassing the Atlas V for the most flights of any operational U.S. booster.

The Falcon 9 flight record includes two premature main engine shutdowns, neither of which affected the primary mission, one failed cargo run to the ISS, and one preflight launchpad accident that destroyed another rocket and its payload, an Israeli commercial communications satellite.

The Atlas V, which began flying in 2002, had one issue with a Centaur upper stage in 2007, but the satellites were able to maneuver to their intended orbits. The rest of its missions have been completely successful. Though Boeing will repeat the Starliner’s uncrewed orbital flight test, the December 2019 launch certified the Atlas V for human spaceflight.

Work Amid Pandemic

NASA and SpaceX have a full plate of work ahead of a targeted May 22 Demo-2 Flight Readiness Review (FRR), which will take place in part virtually and partially at Kennedy due to COVID-19 travel restrictions and workplace shutdowns.

The final test of SpaceX’s Mk. 3 parachutes is scheduled for early May. Testing was delayed by a March 24 accident that resulted in the loss of a Crew Dragon test article, which became unstable as it was hoisted into the air by a helicopter.

SpaceX on April 24 completed a successful static test fire of the Falcon 9 rocket that will launch Behnken and Hurley on the Demo-2 mission.

Outstanding Crew Dragon certification products include verification closure notices, variances and hazard reports, NASA said, adding that specific items are proprietary.

Ahead of the FRR, NASA and SpaceX will hold Operations, Stage Operations, Launch and Flight Test readiness reviews. Multiple NASA executives sign the Certification of Flight Readiness after the FRR, with senior approval coming from Loverro, a seasoned national security and space policy guru recruited to NASA six months ago. Oversight of Demo-2 will be his first human spaceflight.

NASA has yet to decide how long the Demo-2 mission will last. While operational Crew Dragon capsules will have 270-day orbital lifetimes, the spacecraft being used for SpaceX’s final Commercial Crew flight test can stay docked at the ISS for up to about 120 days.

Behnken and Hurley will transfer to the ongoing Expedition 63 crew as flight engineers, but the assignment is temporary. Staying longer would ease the ISS staffing shortfall—Expedition 63 is composed of just three crewmembers, half the usual number. But bringing Behnken and Hurley home to complete the Demo-2 mission means NASA can move on with the certification process needed for SpaceX to begin operational missions.

The agency is counting on the Expedition 64 crew to include astronauts launching on SpaceX’s Crew-1 flight later this year. NASA remains in negotiations for an additional seat for a U.S. astronaut aboard a Russian Soyuz capsule. Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy, who arrived at the ISS on April 9 along with cosmonauts Ivan Vagner and Anatoly Ivanishin, took NASA’s last paid ride on a Soyuz.

Cassidy’s backup, astronaut Stephen Bowen, has returned to the U.S., and the agency currently has no astronauts in training in Russia, says NASA spokeswoman Brandi Dean.

“Several Commercial Crew astronauts are in training for long-duration station missions,” she wrote in an email to Aviation Week. “No other official assignments have been made.”

NASA on March 31 added astronaut Shannon Walker and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency astronaut Soichi Noguchi to the SpaceX Crew-1 mission. NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins and Victor Glover have been training for the flight, which includes a long-duration stay on the ISS, since August 2018.

Meanwhile, Boeing’s operational Starliner missions will not begin until 2021 at the earliest. The Starliner flight-test crew, now back in line behind another uncrewed mission, includes Boeing astronaut Chris Ferguson, formerly with NASA.

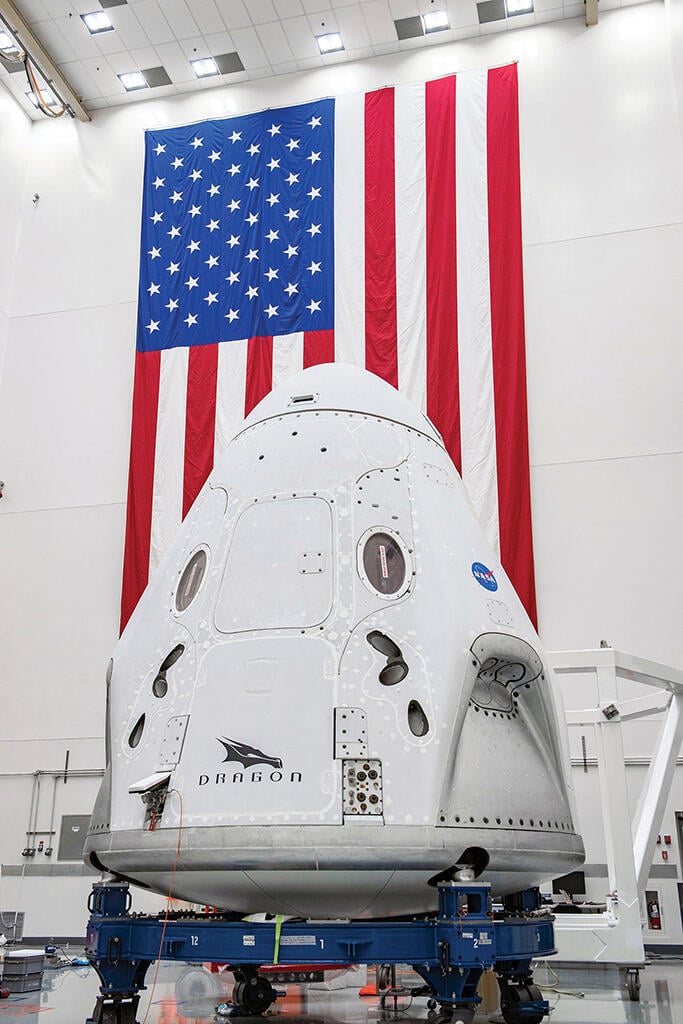

During his last spaceflight, Ferguson and his STS-135 crewmates left behind a U.S. flag on the station to be returned by the first crew launching to the station from U.S. soil. That milestone is now within SpaceX’s reach.

But NASA later added a second flag to emphasize the importance of having two independent U.S. crew transportation systems to orbit. It is a strategy that so far is the clear winner.

Editor's note: This article was updated with new information about the Falcon 9 static test fire completed April 24.

Comments