It is not just the length of time that humans have been continuously living and working in space that is impressive, though 20 years is a milestone in and of itself, but also how the 15 nations in the International Space Station program have maintained a partnership that thrives despite national and international strife.

It began with technical and operational standards, allowing hardware that had never been in contact on Earth to connect and function together upon reaching low Earth orbit (LEO). NASA is now looking to extend those standards for programs and partnerships beyond LEO under the Artemis program, which aims to return astronauts to the Moon as a precursor to human missions to Mars.

(AW&ST Nov. 12-25, 2018, p. 30).

- Businesses are testing LEO waters

- ISS is the model for future joint missions

“In the early days of ISS design and assembly, everyone was just incredibly nervous,” recalls John Mulholland, who now serves as ISS program manager for lead contractor Boeing. “One of the biggest risks was: ‘Are we going to be able to assemble all of these [modules] on orbit and have everything work the first time successfully?’

“The space shuttle program had put a lot of plans in place to be able to return a module and then fly it back. We never had to do that,” he adds. “Looking back, [the ISS] was just an incredible engineering achievement, probably the most incredible engineering achievement of our lifetime.”

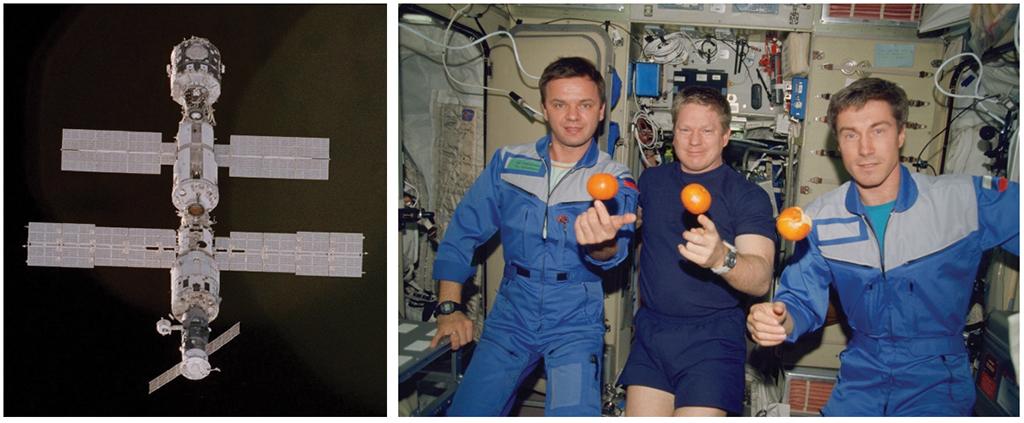

The station’s base block, a Russian--built, U.S.-owned propellant module named Zarya—Russian for “dawn”—was launched into orbit on Nov. 20, 1998. The first of what would become 37 U.S. space shuttle assembly missions followed in December to attach connecting Node 1, Unity.

Delays building the third component, Russia’s Zvezda service module, which was needed for early crew habitation, put construction of the outpost on hold for two years. Zvezda (Russian for “star”) finally reached orbit on July 12, 2000, and docked with Zarya on July 25, kicking off a decade of assembly and outfitting missions by the U.S. and Russia.

The first crew, Expedition 1—NASA astronaut William Shepherd and Russian cosmonauts Sergei Krikalev and Yuri Gidzenko—lifted off aboard a Russian Soyuz rocket on Oct. 31, 2000, and reached the fledgling station two days later. The orbital outpost, now about the size of a six-bedroom house, has been permanently staffed by rotating crews of astronauts and cosmonauts ever since.

“The demonstration that nations can come together and pull off something magnificent and sustain it for 20 years is probably the most significant achievement of the International Space Station,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine tells Aviation Week. “It is definitely a marvel of technology, but I think it’s also a marvel of diplomatic power, not just for the United States but for all of the partners that are involved in it. It really shows that when we all collaborate we can do things that have sustainability and durability.”

After a 10-year hiatus, the U.S. and Russia are again preparing to add modules to the ISS, though the U.S. facilities will be owned and operated not by NASA but by private companies. Nanoracks, which broke into the LEO services business by integrating experiments and launching cubesats from the ISS, is preparing for the November launch of its Bishop Airlock, which will become the first U.S. commercial module permanently attached to the station. (The Bigelow Aerospace-owned Bigelow Expandable Activity Module, known as BEAM, joined the ISS in 2016 as a technology demonstration, not a commercially operated facility.)

Bishop is to be followed in 2024 by a module owned by Axiom Space, which intends to parlay a $140 million contract with NASA for docking rights at the Harmony Node 2 forward port into a privately owned (and eventually free-flying) commercially operated platform in LEO.

Meanwhile, Russia’s Roscosmos State Corp. for Space Activities is preparing for a May 2021 launch of the Nauka multipurpose laboratory module, followed six months later by the arrival of a five-port docking hub for the Russian segment, says Roscomos Director General Dmitry Rogozin.

The growth spurt coincides with the resumption of ISS crew rotation missions from the U.S., a service that has been unavailable since the space shuttles were retired in 2011. Looking for a safer and less expensive alternative, NASA shifted to fixed-price contracts and partnerships to deliver first cargo and then crews to the ISS.

U.S. station resupply lines are currently operated by SpaceX and Northrop Grumman, with Sierra Nevada Corp.’s Dream Chaser winged spaceplane expected to join the fleet in 2021. SpaceX and Boeing have NASA contracts to fly crew, with the first operational Commercial Crew mission, SpaceX Crew-1, now targeted for launch in November.

The arrival of Crew-1, with NASA astronauts Michael Hopkins, Victor Glover and Shannon Walker and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency astronaut Soichi Noguchi, will mark the beginning of five-member U.S. Operating Segment staffing, which will dramatically increase the time available to conduct research, the primary purpose of the station.

To date, the station has hosted nearly 3,000 investigations involving scientists in 108 countries from a wide range of fields including pharmaceutical research, fluid physics, chemistry, human physiology, biotechnology, Earth science, astronomy and astrophysics. “To my knowledge and to many others’ there is no other international activity that has been as successful as [the ISS] has been,” says Joel Montalbano, NASA’s ISS program manager.

NASA is counting on a growing commercial space sector so that it can free up funding to push human exploration and development into deep space with the Artemis program. The agency intends to rely on commercially provided services and platforms to continue research and technology demonstrations in LEO, especially after the ISS comes to an end.

The 15-nation ISS partnership, which includes the U.S., Russia, 11 European nations, Japan and Canada, is looking to keep the station operational at least until 2028-30, and possibly longer. NASA needs the ISS or other LEO platforms to test life support, exercise equipment and other technologies for long-duration missions to the Moon and eventually Mars.

“As we go farther away from low Earth orbit, where we don’t have a capability to resupply very easily—if at all—we have to understand the reliability of these systems. We have to be able to plan for the right number of spare parts and be confident that we’re going to have a successful mission,” says NASA acting ISS director Robyn Gatens.

“What we’ve learned so far with more than 10 years of operating the [life support] system on ISS is that we’re still learning about it,” she says.

Other U.S. agencies besides NASA fund microgravity research aboard the ISS, which also operates as a national laboratory. “There are a lot of things that have been discovered or developed in microgravity that have done good for people on Earth,” says Michael Lopez-Alegria, a former NASA astronaut and ISS commander who will be training and accompanying three paying passengers to the orbital outpost under a contract with Axiom. The flight, known as AX-1, scheduled for late 2021, is among a handful of private crewed orbital flights in development.

“We’ve been living in orbit for 20 years now, and we’ve kind of made access to at least low Earth orbit become—I hate to say ‘routine’ because space is never routine—but something that is reliable and can be counted upon,” says Lopez-Alegria. “That really enables a transition from government to commercial entities to establish an LEO economy that then supports beyond-LEO exploration. It’s changing the paradigm from making sojourns into space to actually inhabiting space for the first time.”

NASA is parlaying its 20 years of experience operating the ISS into a new human exploration initiative beyond LEO. For Artemis, commercial partners are being brought in early, with the requirement that they finance some of the hardware development. In exchange, the partners retain their intellectual property and can sell their services to customers outside of NASA.

The public-private partnership model, first tested with ISS cargo resupply services, shifts to human spaceflight with the first crew rotation mission scheduled to launch in November. “Very reliable, cost-effective crew transportation is the basis for everything else,” says Kathryn Lueders, associate administrator for NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate.

For Artemis, NASA intends to retain a traditional role transporting astronauts to and from lunar orbit using expendable Space Launch System (SLS) heavy-lift rockets and reusable Orion capsules, programs that have been in development for more than a decade. The SLS and an uncrewed Orion spacecraft are now expected to launch on a flight test around the Moon in November 2021. That would be followed by a crewed flight test in 2023, with the goal of landing two astronauts on the lunar south pole before the end of 2024.

The lunar landing depends on at least one of NASA’s three industry partners—Blue Origin, Dynetics and SpaceX—having a system ready to transport crew between lunar orbit and the surface of the Moon. NASA is requesting $3.2 billion for the program for fiscal 2021. “If we can have that done before Christmas, we’re still on track for a 2024 Moon landing,” Bridenstine said in September.

The initial lunar foray may bypass NASA’s planned Gateway, a staging platform and technology testbed in lunar orbit that, unlike the ISS, will be designed to be operated with or without crews. “The way we’re going to be assembling and deploying our equipment around the Moon is not going to be as challenging as assembling the space station, but only because we had the space station first,” Lueders says.

The challenge will be in extending ISS logistics, supply and crew transportation systems from LEO to cislunar space, she adds. “We have to be able to show that spaceflight is routine,” says Lueders. “And for a lunar mission that is very tough for us.”

The ISS partnership also serves as the role model for future international cooperation in space projects. NASA took the lead in creating an agreement, known as the Artemis Accords, which so far has been signed between the U.S. and Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the United Arab Emirates and the UK.

The document is based on the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, otherwise known as the Outer Space Treaty. Specifically, the Artemis Accords reiterate the commitment by the U.S. and signatories to explore space for peaceful purposes, register objects that are put into space, provide emergency rescue services to astronauts and openly distribute scientific information, among other practices.

“What we’re trying to do is establish norms of behavior that every nation can agree to so that we can avoid any kind of misperception or anything that could result in conflict,” Bridenstine says.

Jointly operating the ISS over the last 20 years has not been without problems. The 2003 Columbia accident ultimately led to the U.S. decision to retire the space shuttles, putting the responsibility of staffing the station solely on Russia. That arrangement continued despite the political and economic fallout stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014.

Five cargo ships—three Russian, one SpaceX and one Northrop—were lost between 2011-16, complicating resupply efforts. In particular, the SpaceX Falcon 9 accident in June 2015 claimed a docking adapter needed for upcoming U.S. crewed capsules.

In October 2018, a Soyuz capsule carrying two members of the ISS Expedition 57 crew made an emergency landing after a failed launch, the first Soyuz launch abort in 35 years. There have been emergency spacewalks to replace failed components and to hunt for a leak in a docked Soyuz spacecraft.

“If you think about all of the things that have to happen to keep our crew onboard and healthy and to maintain the systems—when anomalies occur, fly the right spare parts, plan the EVAs [extravehicular activity/spacewalks] and fix whatever happened—all the while conducting all of this research, that by itself is an amazing achievement,” Gatens says.

Recent upgrades to lithium-ion batteries and planned replacement of the solar arrays could keep the station operational for another decade. “We keep evolving this platform and expanding what we can do with it,” Gatens says. “We’re celebrating this anniversary and what we’ve accomplished so far, but we’re on the cusp of huge payoffs from this platform.”

NASA’s Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight development, adds: “We have had a generation of humanity that has essentially lived their entire lives with people in space continuously. It probably does not feel profoundly different day-to-day for most people. But I think we will look back on this time and see that this was an inflection point in human history and in our exploration of the cosmos.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated with more information about the Artemis program, ISS mishaps and the future of the station.

Comments

Where is the probing, the questioning in this article?

Bernard Biales

Keep in mind that the LHC, a similar design to the SSC, has produced almost no new physics, despite massive cost and effort. It has only confirmed the Higgs, which was described and named 30 years before.

When people say we should send probes to Mars instead of human exploration, I reply "Mars is already mapped far better than Earth. The taxpayers who fund space programs have no further interest in learning more details about Mars unless 'we' are going. The probes efforts will shrivel unless 'we' humans are going there."