Competition For Australia’s Military Satellite Contract Looks Fierce

After years of purchasing commercial communications systems or relying on and having its military forces draw on allied capabilities, the Australian Defense Force is hunting for its own next-generation military satellite communications system.

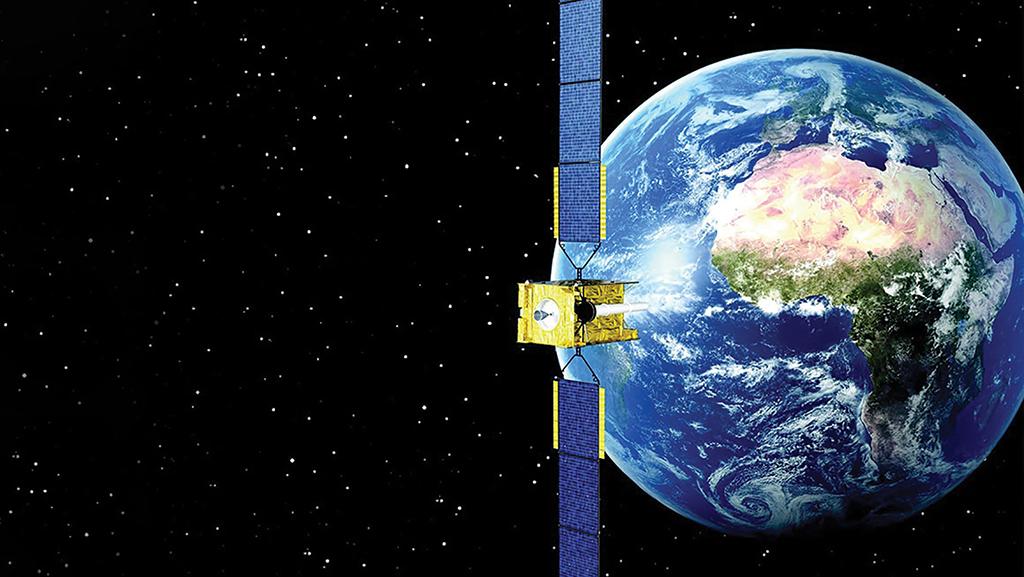

In April, the Australian government released a request for tenders for the Australian Defense Satcom System (ASDSS). The full system includes a set of geostationary satellites, an international agreement that provides for assured access to global coverage in exchange for access to ASDSS and a commercial component to account for gaps in coverage or surge needs.

This particular contract for Joint Project 9102 (JP9102), potentially worth $3.5 billion for the winner, is for geostationary satellites to be controlled and operated by the Australian Defense Force. The Australians want a narrowband or legacy UHF wideband capability as well as wideband commercial and military Ka-band technology and X-band services for the Pacific and Indian Ocean regions. The system must include facilities and fixed anchor stations and an information and communications technology management system.

Airbus Defense and Space

Airbus Defense and Space is likely to offer an enhanced version of the Skynet family of military communications satellites. The European OEM says it wants to make Australia’s transition to a sovereign capability “as easy as possible.”

Martin Rowse, Airbus Defense and Space’s JP9102 campaign lead, describes Australia as having an expeditionary force with a wide global footprint, noting that Canberra is equipping itself with new platforms including Lockheed Martin F-35s, UAS and Airbus A330 MRTTs. He compares Australia’s needs with those of the UK, which maintains interoperability with the U.S. but also has its own capabilities.

Australia is seeking a proven platform similar to Skynet, which Airbus has provided for the UK Defense Ministry for the last 18 years and which supported British operations in the Middle East. Airbus says it plans to enhance that capability to meet the JP 9102 requirements.

While Australia has growing commercial nano-to-small-satellite manufacturing capabilities, maintaining and replenishing a constellation is still expensive, and Canberra wants the resilience, assurance and reliability that a large geostationary satellite can offer.

Rowse expects JP9102 Phase 2 could be a mixed constellation of low-Earth-orbit satellites and Australian-built smallsats packed with defense functions. Australia has also launched a space-based intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance capability under Defense Project 799 Phase 2.

Airbus has set up a consortium—Team Maier—consisting of local space and defense small and medium-size enterprises such as space infrastructure company UGL and UHF provider Blacktree Technology.

Boeing

Boeing, which lays claim to being an incumbent, is hoping to leverage its U.S. military satellite technologies and upgrades to build a system that can win the contract.

Australia first partnered with the U.S. for services from its Wideband Global Satcom (WGS) spacecraft in 2007. The constellation is based on Boeing’s 702 commercial satellite bus, which operates in Ka- and X-band. Boeing continues to upgrade it for protected tactical satellite programs for the U.S. Space Force with additional anti-jamming capabilities. For commercial customers such as O3b, the company has built the 702X software-defined satellite that can operate in multiple orbits and selectively distribute bandwidth.

After the initial development, installation, operations and five years of support, Australia may later expand the system to include intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance or space domain-awareness missions, according to Matt Buckle, director of emerging markets at Boeing Defense Australia.

“Our solution is to bring the best of the U.S. through to Australia,” Buckle says. That means partnering with Australian companies such as Saber Astronautics, known for next-generation space visualization, and Clearbox, which has a background in software development and integration.”

Lockheed Martin

Lockheed Martin also plans to leverage existing commercial satellite buses—in particular, its line of LM2100s. But it also may draw on smaller LM 400 or LM 50 spacecraft and is highlighting a still-developmental on-orbit servicing platform that could provide maximum flexibility to the Australian Defense Force.

“Our satellites will have reprogrammability built into the system so that we can bring in new waveforms, and the Australians can develop their own way to be more efficient with spectrum or less vulnerable to jamming,” says Erik Daehler, Lockheed’s program manager for protected communications in military space.

Australia would have the ability to bring on new terminals, operate its own systems and interoperate with the U.S. and UK and future partners. The Australians will need to develop industrial base content, including sensors and effectors involving hardware and code for network solutions. Lockheed wants the Australians to take on as much of that content as possible and help build an entire cottage industry.

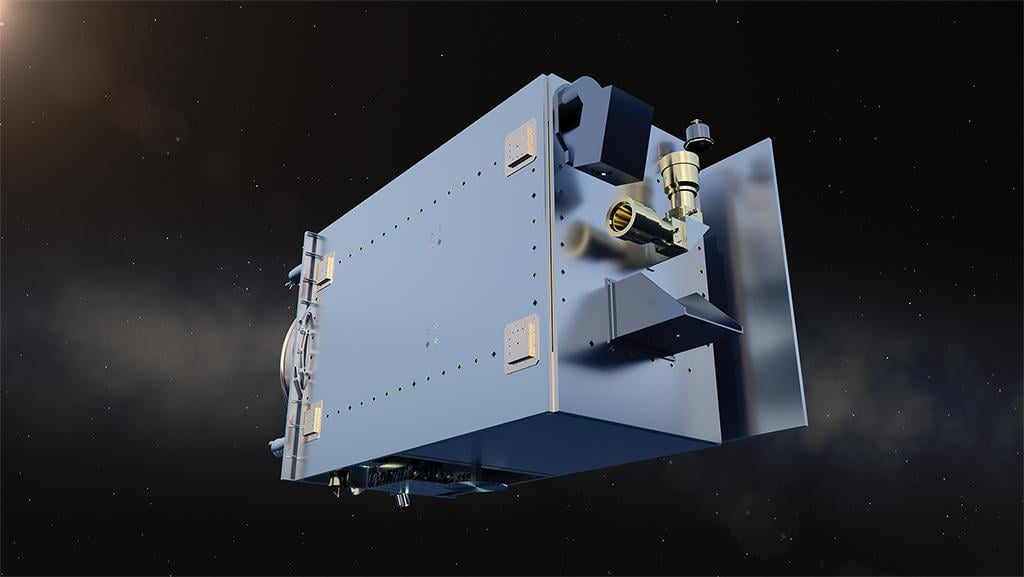

Lockheed has discussed the production of satellite-augmentation vehicles with Australia. One such vehicle is the company’s Augmentation System Port Interface, an autonomous docking port that enables an on-orbit satellite to be upgraded or recovered.

Like Boeing, Lockheed also plans to work with Australia’s Clearbox Systems, integrating technology from Clearbox Systems’ Foresight ESM software application.

“If we look at a JP9102, we do consider what the future looks like,” says Eric Brown, senior director of military space mission strategy at Lockheed. “It’s something that is really responding to the threats of tomorrow and is flexible.”

Optus

Optus Australia, one of the nation’s largest telecommunications companies, is leading Team Aussat in its bid to win the contract. Optus, owned by Singapore-based Singtel, will team with Raytheon Australia and Thales Australia.

“The bid team, Team Aussat, has a unique proposition being the only team with an unrivaled history of owning and operating satellites in Australia, by Australians, for Australians—drawing synergies from two partner companies with their exceptional pedigrees in building and delivering world-class defense capabilities,” says Optus Chief Executive Kelly Bayer Rosmarin.

She stresses that the Optus team is uniquely positioned to leverage partnerships with local universities and attract new graduates to the space sector.

Optus has been a leading satellite provider in Australia, having launched 13 spacecraft since 1985. In 2003, the company lofted the C1, a part-commercial, part-military Ku-band communications satellite.

Comments

Incidentally, if Australia wants its next-generation military satellite communications system to actually be "its own", it will have to build and launch the satellites by itself.