Although rare relative to the total number of flights, wildlife strikes to civil aircraft increased more than nine fold from 1990 to 2019, according to a joint report by the FAA and U.S. Department of Agriculture.

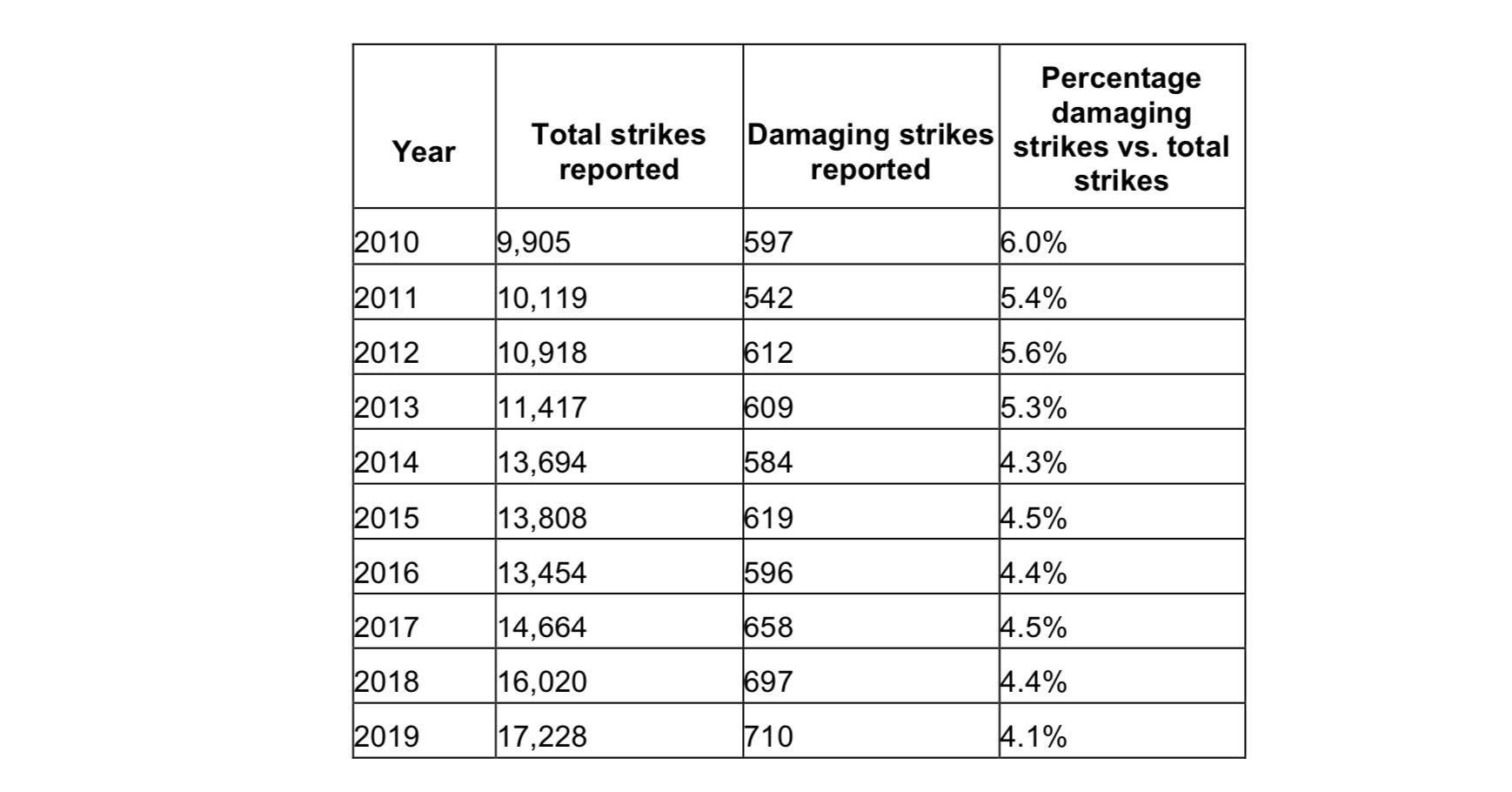

The number of wildlife strikes reported annually to the FAA increased from 1,850 in 1990 to a record 17,228 in 2019. While the overall number of strikes rose dramatically, the number of reported damaging strikes increased only slightly after 2010 and remained below the record of 743 damaging strikes recorded in 2000, the report found.

Factors contributing to the threat of aircraft collisions with wildlife are increasing populations of large birds and increased air traffic by quieter, turbofan-powered aircraft, the agencies said. The annual cost of wildlife strikes to the civil industry in 2019 was projected to be 116,984 hours of aircraft downtime and $205 million in direct and other monetary losses.

Released by the agencies in February 2021, the report represents a summary analysis of 30 years of data from the FAA’s National Wildlife Strike Database (https://wildlife.faa.gov/home). There were 231,320 strikes reported from 1990-2019, of which 227,045 were in the U.S. and 4,275 involved U.S.-registered aircraft in foreign countries.

The number of U.S. airport with reported strikes increased from 335 in 1990 to a record 753 in 2019. Of the 753 airports, 420 were certificated for passenger service and 333 were general aviation (GA) airports. Over the period of the study, strikes were reported at 2,091 different airports.

In 2019, birds were involved in 94% of strikes, bats in 3.2%, terrestrial mammals in 2.3% and reptiles in 0.5%.

Over the report period, 72% of bird strikes with GA aircraft occurred at or below 500 ft. above ground level (AGL). About 29% of strikes were reported above 500 ft. AGL, but represented 51% of damaging strikes, the report found.

In one example contained in the report, a Bell 206 helicopter collided with a red-tailed hawk at 1,200 ft. over Texas in January 2019. “The hawk penetrated [the] windshield. The pilot, with minor injuries, made an emergency landing at nearby airport with dead hawk in his lap.”

The record height for a reported bird strike involving a GA aircraft in the U.S. was 24,000 ft. AGL.

The aircraft components most commonly reported as struck by birds were the nose/radome, windshield, wing/rotor, engine and fuselage. Aircraft engines were the component most frequently reported as being damaged by bird strikes.

“Management actions to mitigate the risk have been implemented at many airports since the 1990s; these efforts are likely responsible for the general stabilization or decline in reported strikes with damage,” as well as a decline in the percentage of strikes with a reported “negative effect-on-flight,” the agencies said.

“However, much work remains to be done to reduce wildlife strikes,” the report advises. “Management actions at airports should be prioritized based on the hazard level of species observed in the aircraft operating area.”

The manual “Wildlife Hazard Management at Airports,” available at the wildlife.faa.gov website, provides guidance for conducting wildlife hazard assessments and in developing and implementing wildlife hazard management plans.