When I think back to my last several unstable approaches — I’ve had a few over the years — there are usually a few reasons behind each. Chances are they resulted from actions by other aircraft, instructions by ATC, sudden weather changes, or conduct internal to my aircraft — in other words, me. While there are things we can do to shape the outcomes of the first three inciting events, they are for the most part outside our control. The last item, however, is within our grasp of control. Or is it?

It has almost become an unwritten rule: If you aren’t stable by 1,000 ft. when in instrument meteorological conditions (IMC), go around. There is much discussion about how to wire in the correct vertical and horizontal parameters, establishing stable approach criteria, combatting pilot continuation bias and normalizing the go-around decision. In fact, I’ve done just that in these pages (“New Approach to Stabilized Approaches,” May 2014).

But there is another facet of this problem that hardly gets any discussion at all: checklist design. If you extend the landing gear at glideslope intercept, you will typically have about 2 min. remaining until touchdown. More importantly, you will have less than a minute prior to your stable approach height when in IMC. Is that enough time for the crew to accomplish all checklists, fly or monitor the approach, and look outside for the landing environment?

I heard of a Hawker’s before-landing checklist with 16 items on it, 15 of which came after the gear is extended. Bad design. If the pilots are busy ticking off 15 things to do just a minute or so prior to landing, how much effort can be focused on keeping things, um, stable? Of course, aircraft design plays a role in checklist design, but there are things we can do as operators to reduce the destabilizing effect of having to accomplish too many tasks just prior to landing.

How Much Time Once the Gear Is Down?

A good time to conduct the before-landing checklist is after the landing gear has been extended, which, in turn, is best accomplished just before or upon intercepting the glideslope. Delaying gear extension until glideslope intercept can be said to improve approach stability, since adding drag when starting down reduces (or can even eliminate) the need to reduce thrust settings.

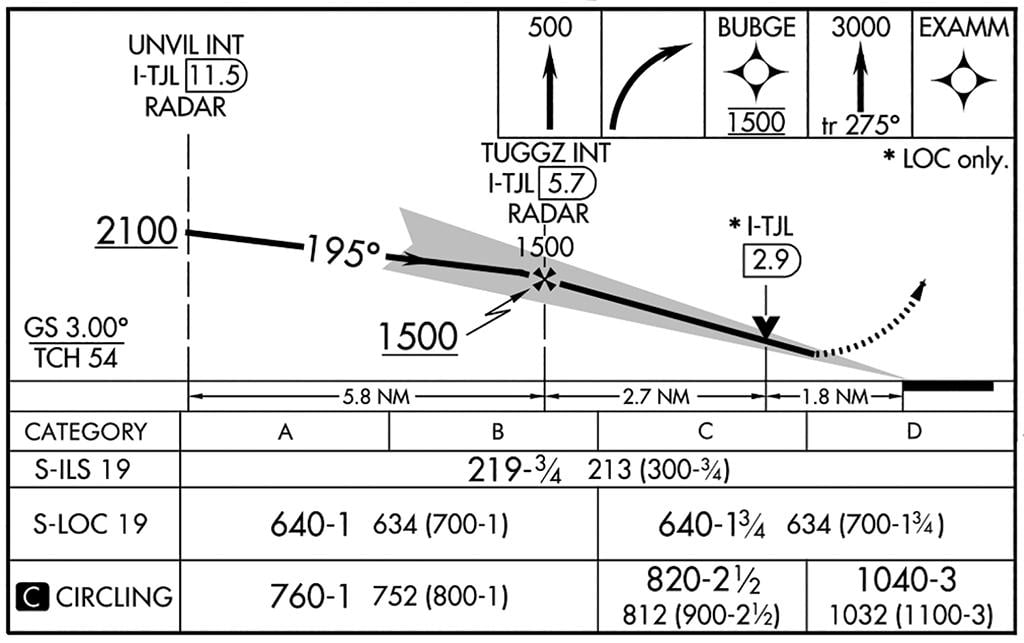

So, how much time does that give you to accomplish any checklists? The ILS Runway 19 at New Jersey’s Teterboro Airport (KTEB) can provide a useful working model. Since the runway is a mere 6 ft. MSL, it also makes the math easy. Glideslope intercept happens at 1,500 ft MSL and 4.5 nm from runway end. At a hypothetical approach speed of 120 kt. ground speed (to make the math easy), we are traveling at 2 nm per minute, or 1 nm every 30 sec. In the example approach, we will have 2 min., 15 sec. until crossing the runway threshold to accomplish the before-landing checklist.

But if we are in IMC, we will want to have that done no later than 1,000 ft., our stabilized approach height, giving us only one-third the altitude and one-third the time, so just 45 sec.

The pilot flying (PF) and pilot monitoring (PM) are working as a team getting the airplane fully configured, on speed, on course, on glidepath and in a position to land no later than stabilized approach height. And once it is there, they need to keep it there for the landing. Keep in mind the PM should be simultaneously monitoring the approach progress as well as the radios. The PM will also have to look outside with increasing frequency as the descent progresses. Is 45 sec. enough time to do all of that and accomplish a properly designed checklist?

How Should a Checklist be Designed?

It may seem odd to us today, but early aviators survived nearly 30 years of aviation without formalized checklists. Doing everything that needed to be done was just a part of the pilot mystique. But with the arrival of the airplane that became the Boeing B-17, people realized there was too much for pilots to do to leave those tasks to memory.

An early model of that airplane crashed in 1935 when the very competent test pilots forgot to unlock the controls. The design was almost abandoned, thinking it was just too complicated an airplane for any pilots to fly. However, the U.S. Army Air Corps proved otherwise by developing checklists for its crews for takeoff, flight, landing and after landing. We modern aviators just accept that checklists are a part of the job. Or, at least most of us accept that.

Are checklists required? FAR Part 91.503 says that we need to have checklists accessible at our “pilot station” for each flight, but not that we necessarily have to use them. You can argue that Part 91.13 (“Careless or Reckless Operation”) compels us to do so. I would agree with that, but not everyone does.

Regardless of whether you regard checklists as mandatory or optional, there is a right way and a wrong way of designing them. While the following from FAA Order 8900.1, Volume 3, Chapter 32 is specifically aimed for Parts 91K, 121, 125 and 135, I think Part 91 operators would be well advised to adopt the guidance as well:

Most normal procedures do not require incorporation into a checklist. You don’t, for example, need to spell out the individual tasks of landing the airplane.

Checklists should be kept as short as practical to minimize “heads down” time.

Technologically advanced aircraft can reduce the number of checklist items, relieving flight crew workload.

In two-pilot aircraft, both pilots should challenge and respond to critical flight guidance items on approach.

Checklists should not be relied upon to initiate changes in aircraft configuration. These changes should be keyed to operational events, such as glideslope intercept.

Manufacturers have wide latitude in checklist design and for the most part look for consistency among aircraft models. The “checklist philosophy” varies not only among planemakers but also with regulatory agencies and operators. Pilots flying multiple types may have added challenges when these designs vary even slightly.

Two Examples

Some of the best and worst before-landing checklists I’ve seen come from Gulfstream. Here is one from the latter category, for the G150.

Before Landing

- Landing Reference Speed (Vref) . . . CONFIRM & SET

- WINDSHIELD HEAT . . . AS REQUIRED

- ANTI-ICE & DEICE . . . AS REQUIRED

- IGNITION . . . AS REQUIRED

- APR ARM . . . ARM

- Landing Gear . . . DOWN/3 GREEN

- ANTI-SKID . . . CHECK ON (LIGHTS OUT)

- Hydraulic Pressure . . . CHECK MAIN & AUX

- THRUST REVERSE ARM . . . ARM

- Brake Lever . . . OFF

- ENGINE SYNC . . . OFF

- GROUND A/B . . . LAND

- SLATS/FLAPS . . . FLAPS 40°

- Autopilot . . . DISENGAGE

I think most of us mentally connect the before-landing checklist with the act of extending the landing gear. When we get rushed, we think “got to put down the gear,” followed by “what else?” Hopefully, the “else” is the checklist, but that can become rushed if it’s long and doesn’t lead with the most important item.

If at all possible, the before-landing checklist should begin with the landing gear so as to turn the whole thing into a callout: “Gear down, before-landing checklist.” That makes it less likely you will forget to call for the checklist.

The five items on the G150’s list prior to the landing gear are apt to be forgotten in the heat of battle. Some Gulfstreams, but not this one, have an “in range” checklist for these kinds of things that can be taken care of early. At least three of the items after the landing gear can be accomplished before this checklist: i.e., (5) APR (Automatic Performance Reserve), (10) brake lever and (11) engine sync.

I believe the autopilot item, on an airplane with or without autoland, should be considered a normal pilot duty that doesn’t require inclusion on a checklist. All of the “traditional” Gulfstreams, those originally designed by Gulfstream, cannot be landed with the autopilot engaged, and yet this checklist item isn’t used on those aircraft.

This G150 checklist takes an average of 45 sec. to accomplish, or just enough time from glideslope intercept to our stable approach height, provided there are no other distractions or other demands on the PM’s time. No doubt those distractions will occur, and the PM will be left with less time for monitoring.

Contrast the long and complicated G150 checklist with one from Dassault. The Falcon 900EXy has an exceptionally well-designed before-landing checklist, but to appreciate why, you need to look at the checklist that precedes it.

Approach

- Altimeters (all 3) . . . QNH

- Approach Settings . . . Checked

- LANDING Lights . . . ON or PULSE

- FASTEN BELTS . . . ON

- NO SMOKING . . . ON

- Cabin . . . Ready

- STATUS Page . . . Checked

Before Landing

- Landing Gear . . . 3 Greens

- SLATS/FLAPS . . . 40°

It appears Dassault has made a conscious effort to ensure neither pilot is distracted by checklist duties once the gear, slats and flaps are set for landing. Most aircraft manufacturers fall short of this ideal because quite often aircraft design drives the checklist.

The Impact of Aircraft Design on Checklist Design

The G150 before-landing checklist provides an object example of how aircraft design drives checklist construction. Even after moving the five items that appear before the landing gear and three later items to an earlier checklist, we are still left with five items once the gear is down: (7) anti-skid, (8) hydraulic pressure, (9) thrust reversers, (12) ground air brakes (ground A/B) and (13) slats/flaps. These items cannot really be checked until the gear is down because of the many interdependent systems that rely on aircraft hydraulics or other complicating factors.

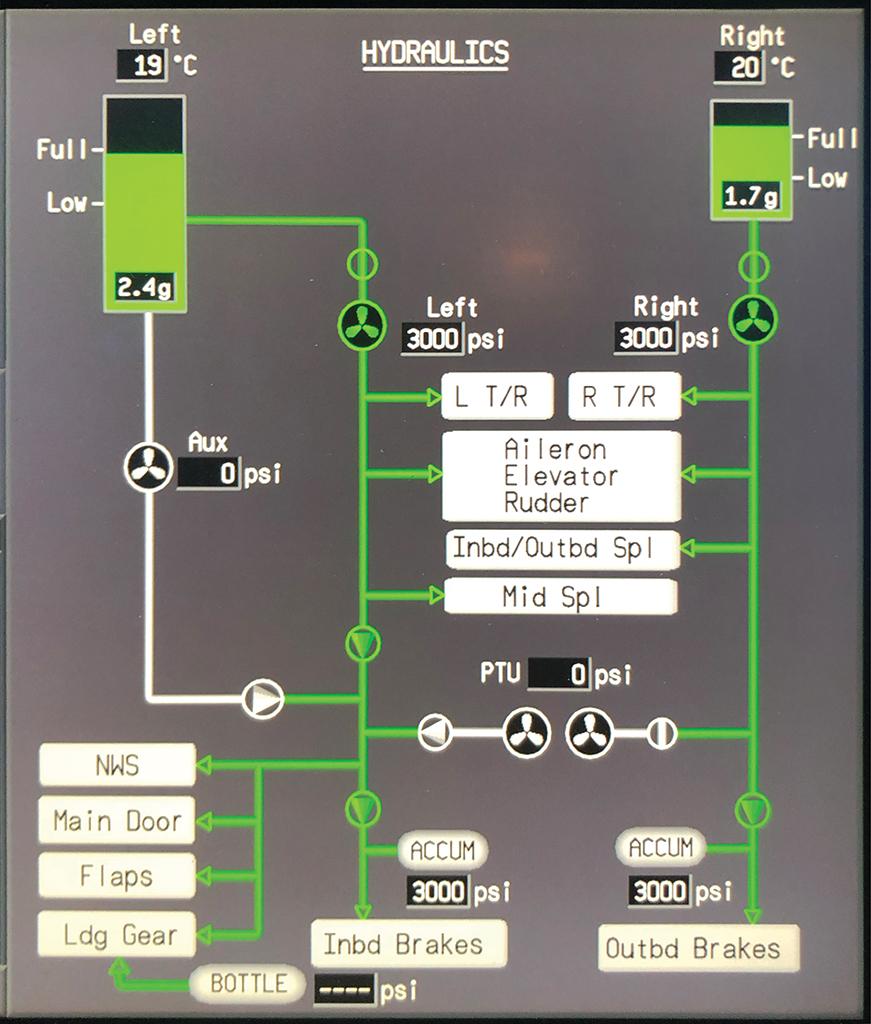

Three-thousand psi is almost a universal pressure for aircraft hydraulic systems, providing a lot of muscle from one part of the airplane to others using relatively compact and lightweight tubing. This has been the method of choice for many years when it comes to landing gear, flaps, slats, ground spoilers and flight controls. A limitation with such a setup is that the fluid under high pressure can deplete itself very quickly when the system develops a leak.

One of the most-feared scenarios is for a leak in the landing gear, flaps, slats or spoilers to deprive the airplane of wheel brakes at the last moment of flight. That is why many manufacturers include a last-minute check of those components and the hydraulic systems once the aircraft is fully configured. You can’t do this check beforehand.

On many aircraft, however, the hydraulic system check can be completed automatically. Most of the critical systems that slow the aircraft prior to landing and then stop it can be electronically monitored to provide a warning should they fail. Shouldn’t this relieve the pilot of the responsibility?

My first aircraft in the large category was the KC-135A tanker. At nearly 300,000 lb., it was large indeed. Designed and built in the 1950s, the aircraft’s crew alerting system consisted of the two pilots, and as a copilot, the blame for missing anything fell to me. I learned early on to mark all the gauges with a grease pencil so I could, at a glance, detect when something wasn’t the way it was hours earlier. It was an admittedly imprecise method, but it helped.

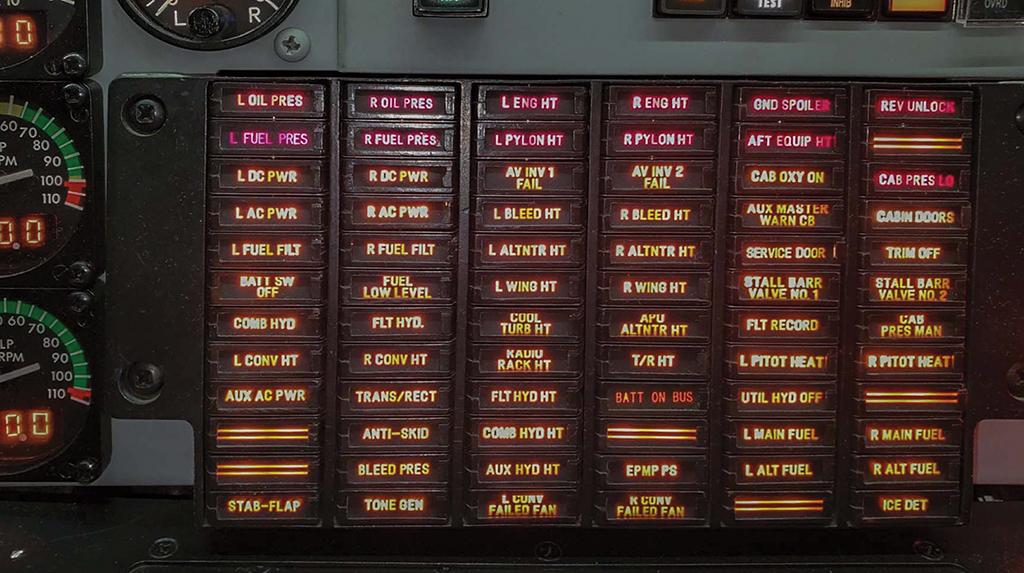

My first airplane with a master caution panel was a Boeing 747-200. It had an array of lights, each connected to an analog switch of some sort along with another light that told me if any of the other lights was triggered.

It certainly beat my grease pencil technique.

The problem, however, was lurking in those analog switches. To illustrate, consider the Gulfstream III’s master warning light panel. Before we do that, however, remember there is a saying in the Gulfstream world: “If you’ve flown one Gee Three, you’ve flown one Gee Three.” That’s because there are a lot of variations within that model.

In the GIII’s that I flew, the warning light on the seventh row, first column was labeled “COMB HYD” and would illuminate in amber if the pressure in what was called the “Combined Hydraulic System” fell below 800 psi. The airplane had a part-time 1,500-/3,000-psi system that would use the higher pressure with the gear or flaps extended. A drop to 800 psi may have been enough to detect a large hydraulic system leak in the landing gear but not enough for a small leak in the flaps. So, the ninth item after the landing gear in our before-landing checklist was to check the hydraulic system pressure on a gauge just forward of the copilot’s inboard knee. It was a checklist item we couldn’t give up and it had to appear after the landing gear and flaps.

The Gulfstream G500 (GVII) also has a 3,000-psi system that drives the landing gear, flaps and wheel brakes, though it is at 3,000 psi full-time. The pressure sensor feeds directly into a digital network that is monitored continuously for faults. A pressure drop below 2,350 psi immediately generates an “L Hyd Pump Fail” and if that were accompanied by a quantity loss below 0.3 gal. and further pressure loss below 1,600 psi, it would generate an “L Hyd System Fail” message.

These modern warning systems are ever-vigilant so we don’t have to be. The requirement to check the hydraulic system after landing gear and flaps extension has been eliminated on many aircraft. Newer aircraft tend to have fewer checklist items because computers do much of the checking and the list has gone to single digits for many modern aircraft.

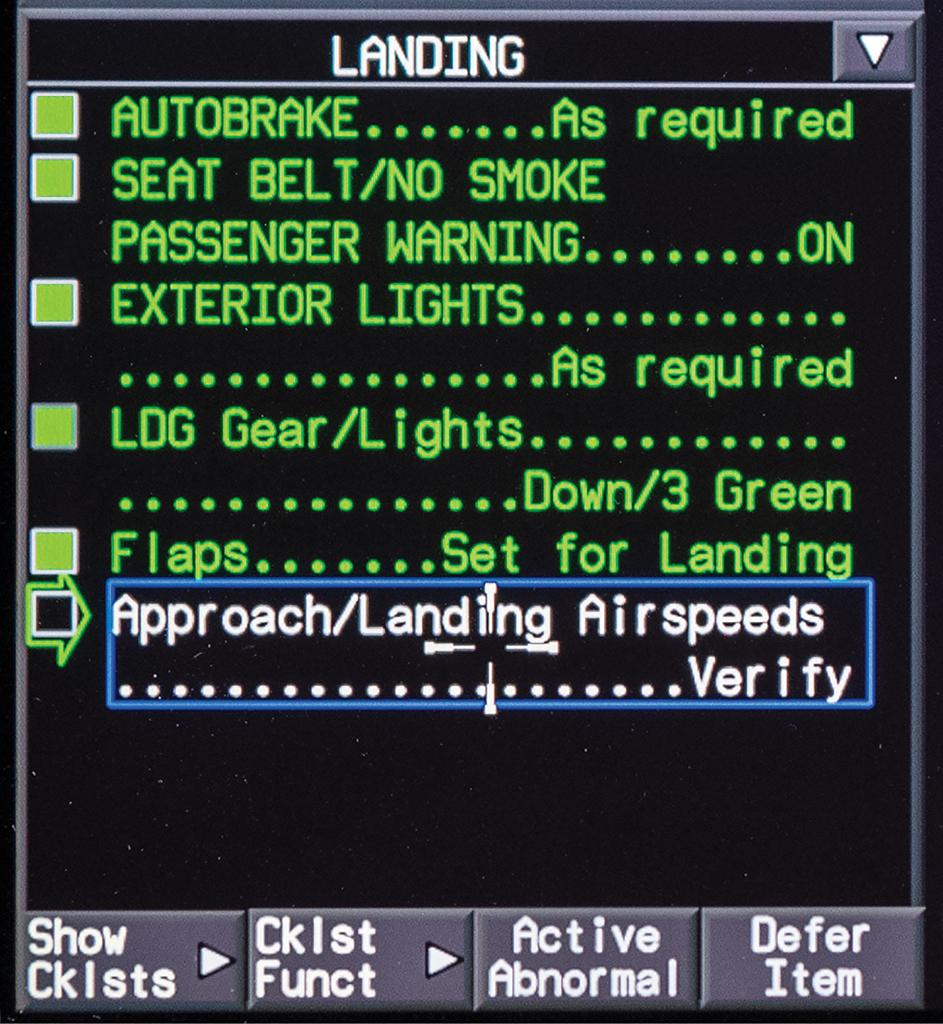

When I saw the Falcon 900EXy before-landing checklist (landing gear, slats/flaps), I was green with envy. Just two items! The before-landing checklist for my Gulfstream G500 is three times longer:

Before Landing

- Autobrake — As Required

- Seat Belt/No Smoke Passenger Warning — On

- Exterior Lights — As Required

- Landing Gear/Lights — Down/3 Green

- Flaps — Down

- Approach/Landing Airspeeds — Verify

But we G500 pilots have an ace up our sleeves: All but one of those six items are completed automatically by our electronic checklist. Setting the autobrakes, for example, also checks the appropriate item. The same holds true for the next four items. All that is left for us to do is to verify our approach and landing speeds.

How to Fix a Broken Checklist

Do you have a flawed before-landing checklist? If so, it could be that the manufacturer designed it in a way to be consistent with other aircraft in its fleet. Perhaps the developers gave the design duties to a non-pilot. Or it could be an old checklist design that didn’t keep up with aircraft modernization. Whatever the reason, your options to improve what you have could be limited.

If you are flying commercially, your checklist will ultimately have to be approved by your operator and approved or “accepted” by the principal operations inspector. If you are flying under Part 91 you have more latitude but should review FAA Order 8900.1, Volume 3, Chapter 32 to ensure you adhere to what the FAA will view as best practices.

Back to the G150. If I were king, this is what I would do with that model’s before-landing checklist. My first step would be to add an in-range checklist for those things that do not have to wait for landing gear extension. Thus:

In Range

- Landing Reference Speed (Vref) . . . CONFIRM & SET

- WINDSHIELD HEAT . . . AS REQUIRED

- ANTI-ICE & DEICE . . . AS REQUIRED

- IGNITION . . . AS REQUIRED

- ENGINE SYNC . . . OFF

- APR ARM . . . ARM

Some manufacturers include an “in-range” checklist prior to landing; some call it an “approach” checklist and ignore the need for something prior to the high workload period just before landing. Using the in-range checklist and eliminating unnecessary items halves the G150’s before-landing checklist to this:

Before Landing

- Landing Gear . . . DOWN/3 GREEN

- THRUST REVERSE ARM . . . ARM

- GROUND A/B . . . LAND

- ANTI-SKID . . . CHECK ON (LIGHTS OUT)

- Hydraulic Pressure . . . CHECK MAIN & AUX

- SLATS/FLAPS . . . FLAPS 40°

In my view, many before-landing checklists can be improved in the spirit of FAA Order 8900 guidelines by:

- Placing all lesser items that do not have to wait for extending the landing gear and flaps in an earlier “in-range” or “approach” checklist.

- Starting the before-landing checklist with an “event initiating” item, preferably the landing gear.

- Eliminating items that are simply normal procedures, such as disengaging the autopilot or autothrottles, if that is normal procedure for your aircraft.

In the airline world, we could once divide aircraft by their automation philosophies, as in Boeing versus Airbus. However, today it seems those two are moving closer to a middle ground. In the business jet world, I have been a fan of all things Gulfstream for decades, and that meant I had to look upon all things Dassault with a certain skepticism. But as with the Boeing/Airbus dichotomy, it seems even a long-time Gulfstream driver can salute the maker of Falcon Jets and the checklists attendant to them.

You may not be able to reduce your before-landing checklist to just two items, but you might be able to get some improvement by reordering items not dependent on landing gear position and eliminating things that don’t belong. The PM should devote as many of the 45 sec. between gear extension and stable approach height to monitoring the PF. Doing so will improve the crew’s chances of flying a truly stable approach.

Comments