Editor’s note: The first part of this two-part article appears here.

The crash of an aircraft operated by All Cargo Carriers (ACC) at Charleston, West Virginia in 2017 can be a lesson about several safety factors.

As background, ACC operated as a scheduled 14 CFR Part 135 cargo airline and was based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The company operated 18 Shorts SD3 airplanes from 12 bases, one of which was Charleston, West Virginia (CRW), and employed 38 pilots. According to the chief pilot, the company flew cargo for Fedex, UPS and DHL.

Crew assignments were to a specific base and there was no rotation schedule. The two accident pilots were the only ones based at CRW, and they flew a regular night schedule together every weeknight from CRW to Louisville International Airport (SDF) and back. The company did not have an initial operating experience program for new pilots such as is required at Part 121 airlines, and the first officer (FO) had begun flying with the captain immediately after her initial checkout. The chief pilot had not followed up to see how the FO was doing; he assumed that if pilots were having difficulties, they would speak up about it.

The FAA Principal Operations Inspector (POI) was asked about ACC’s crew pairing model. He said he was unaware of pilot experience levels or crew pairing issues, but he thought “two pilots flying exclusively together to be beneficial as there was value in familiarity with the other person.”

The company had clearly stated policies about stabilized approaches, circling approaches and callouts. It had a stated policy that safety was the highest priority. It had a multi-use reporting form for employees to use, but no dedicated safety reporting system. The chief pilot mainlined oversight by filling in as a line pilot when someone was sick or absent. He said the most challenging part of his job was managing from afar since he could not see the attitudes and demeanors of his pilots.

The director of training said they sometimes had to hire captains “off the street” and their pilots were “running” to Piedmont, Skywest, Compass and Republic. The company president said his biggest problem was pilot staffing, and that pilots really didn’t stay more than two years. He said an older generation of pilots felt more pride and accomplishment in the job.

The 47-year-old captain resided in Charleston and had been employed with ACC since July 1, 2015. He held an ATP certificate, airplane multiengine land, with commercial privileges for single engine land, a type rating for the SD3 and a rotorcraft helicopter rating. He had 4,368.5 total flight hours, and 1,094.1 hrs. in the SD3. He had flown 70 hrs. in the last 30 days and 609 hrs. in the last 12 months, and his most recent proficiency check was in January of 2017. His last PIC line check was in July 2016. He held a first-class medical certificate with a limitation that he must have available glasses for near vision.

A review of the captain’s previous three days activity showed he had flown the same CRW-SDF-CRW trip each night, and had normal sleep opportunity each day. He was overweight and wore a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine when he slept due to sleep apnea. Analysis of the captain’s CPAP records showed he had used it regularly during the day in the three days before the accident.

ACC had made a standard Pilot Records Improvement Act (PRIA) request for the captain’s record during hiring, but had not obtained the captain’s “complete airman file.” The captain denied he had ever failed any check rides, proficiency checks, IOE or line checks on his employment application, but he had had several failures. Having the complete airman file would have revealed he had not passed his initial private pilot, commercial pilot and flight instructor check rides on the first attempt. While at ACC, the captain had been disapproved on his initial ATP check in the SD3 due to excessive localizer and glide slope deviation, repeated glide slope and sink rate GPWS warnings and failure to go around. He had worked for four different Part 135 operators in Alaska during the three years prior to being employed at ACC.

One person who knew the FO said when interviewed that the captain often slept while in flight. The FO and other company personnel were aware that the captain’s IFR skills “were not strong,” and the FO had told friends of several flights during which the captain made dangerous deviations from standard procedures.

The 33-year-old FO, a former flight attendant, resided in Charleston. She was hired Nov. 16, 2016. She had one prior certificate disapproval, but otherwise had a good record. She had a commercial certificate, multiengine land, with instrument rating and SIC privileges only in the SD3. She had a first-class medical certificate with no limitations. She had accrued 652.4 total flight hours, of which 333.6 was in the SD3. She had the same recent schedule as the captain and was reported to be positive, healthy and well rested during that time. Interviews with her friends and a record of her text messages indicated that she was not in the habit of speaking up.

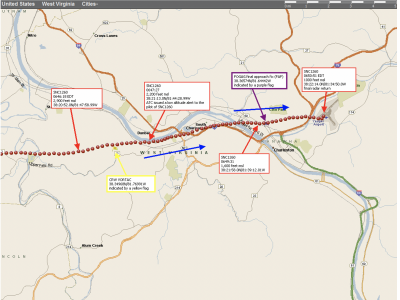

Investigators obtained ATC recorded data of three VOR-A approaches made by the captain to CRW in the 4 months prior to the accident, and found he had descended below FOGAG crossing minimums on all three occasions. Investigators reviewed security camera footage of 17 of the crew’s landings in the previous month, and noted that all the approaches, whether flown by the captain or the first officer, were closer in to the airport than prescribed for an approach in the company FOM.

The accident airplane was a Short Brothers SD3-30. It was built in 1979 as a passenger airplane . and was converted by ACC to a cargo configuration in December 1998 through the installation of several supplemental type certificates. The cockpit voice recorder (CVR) was removed from the airplane during the conversion to the cargo configuration. At the time of the accident the airplane had accrued 28,023.2 hrs. and 36,738 cycles. On the accident flight, the airplane carried 3.874 lbs. of cargo and the airplane was found to be within weight and balance limits.

The Charleston Airport was at an elevation of 946 ft. MSL and the runway, 5/23, was 6,802 ft. long, 150 ft. wide and had a displaced threshold 578 ft. from the approach end of runway 5.

Findings

The NTSB found the probable cause of the accident was the flight crew's improper decision to conduct a circling approach contrary to the operator's standard operating procedures (SOP) and the captain's excessive descent rate and maneuvering during the approach, which led to inadvertent, uncontrolled contact with the ground. Contributing to the accident was the operator's lack of a formal safety and oversight program to assess hazards and compliance with SOPs and to monitor pilots with previous performance issues.

The approach controller erred by not providing the crew the latest weather observation or changing the ATIS. However, given the crew’s history on that approach, it’s doubtful they would have changed their course of action if he had done so. The NTSB concluded that the captain was probably more confident of his ability to land out of an unstable approach than to fly a localizer approach. The FO could have called for a missed approach, but based on her history, this was unlikely.

In its analysis, the board did not address the safety implications of ACC’s fixed crew concept. It may work well in some circumstances but not in others. One recent example of when it did not work well was in the Gulfstream G-IV accident in Bedford, Massachusetts in 2014. The airplane was destroyed in a high-speed abort when the crew attempted to take off with the gust lock system engaged. The board found the crew, who regularly flew together, had neglected to perform a complete flight control check on 96% of their previous 175 takeoffs in the airplane. The familiarity of the two pilots with each other did not prevent, and may have contributed to their habitual disregard of safe operating procedures.

The NTSB did not issue recommendations with this report. However, one of its 2019 “Most Wanted List” issues was “Improve the Safety of Part 135 Operations.”

The board described this accident as an example of “procedural intentional noncompliance,” which was a problem described on their 2015 Most Wanted List. The board prescribed “setting a positive safety attitude” and establishing formal safety and oversight programs as remedies for this problem. These are laudable goals, but certain practical obstacles remain. When you are losing trained pilots faster than you can recruit and train replacements, you will be confronted with hard decisions about pilot selection, performance and retention. If ACC had made a more thorough check of the captain before he was hired, they might well have declined to hire him. If the check airmen had been less forgiving on rechecks and had done more observations and solicited more feedback from crews they might well have forced the captain to go through a disciplined remediation. Or, to borrow a term, they might have “shown him the exit ramp.”

Whether you’re flying a circling approach or hiring, training and supervising pilots, cutting corners can lead to some very serious consequences. The accident at CRW was one of those consequences.

Author’s note: While at the NTSB, I contributed to the drafting of the “procedural intentional noncompliance” part of the 2015 Most Wanted List. I admit it’s a mouthful.