Field workers inject test barrier of colloidal activated carbon at Martha's Vineyard Airport.

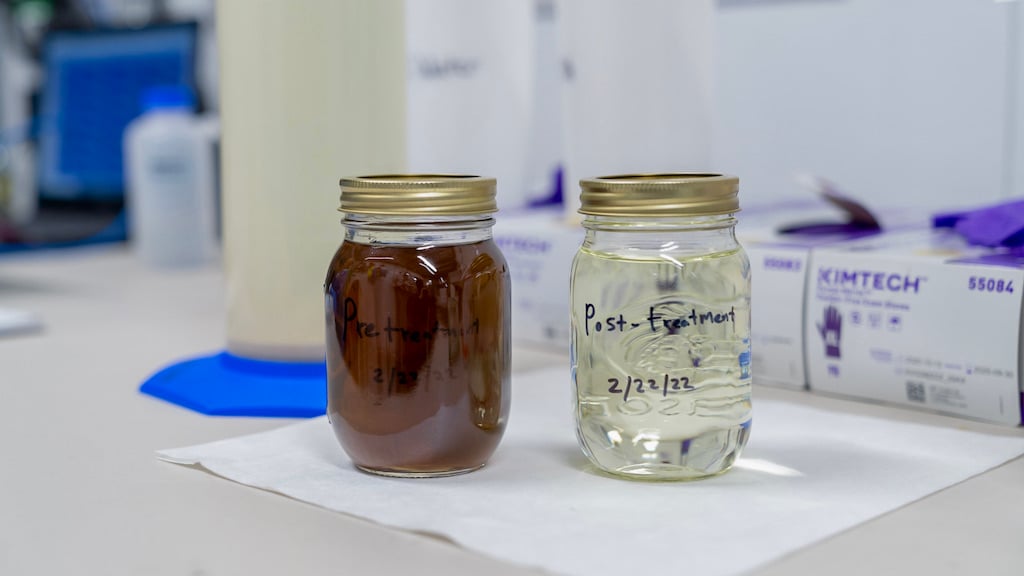

The application of a pilot test barrier of colloidal activated carbon has rapidly reduced groundwater PFAS concentrations detected “downgradient,” or downstream, of a fire-training area at Martha’s Vineyard Airport (MVY), according to the developer of the “PlumeStop” technology.

Four months after PlumeStop was injected into the ground to create a 60-ft.-long permeable reactive barrier (PRB), monitoring samples showed that PFAS concentrations were reduced by 99.8% at a distance of 5 ft. downgradient of the fire-training area, by 78% at 25 ft., and by 57% at 75 ft., reports environmental remediation company Regenesis.

MVY is a county-owned, FAA Part 139 commercial airport located on Martha’s Vineyard, an island off the coast of Massachusetts. It is served by American Airlines, Delta, and JetBlue regional jets on a seasonal basis and by Cessna 402 operator Cape Air year-round.

After confirming the presence of Per- and Poly-fluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) in groundwater at MVY in 2018, Tetra Tech, the airport’s environmental consulting firm, contracted Regenesis to conduct a pilot test of PlumeStop to prevent further PFAS movement away from the site. The installation of a PRB to filter PFAS out of the groundwater, considered an “in situ” remediation approach, was chosen over a more costly “pump-and-treat” solution.

Tetra Tech determined that the best place for the pilot test was immediately downgradient of the area where Aqueous Film Forming Foam (AFFF) had been discharged during recurrent firefighting drills, leaching over time into the underlying groundwater. The goal of the test was to immobilize PFAS at the core of the contaminant plume for 15 years or longer and minimize the plume’s migration away from the site. Another strategy that Regenesis employs is to cut off PFAS migration at the boundary of a property to keep it from moving off-site.

Regenesis performed the PlumeStop application at MVY in December 2022. “Instead of pulling PFAS out of the ground and generating waste, we inject PlumeStop, which is small particles of colloidal activated carbon—1-to-2-micron-size activated carbon particles—that are suspended in a polymer,” says Maureen Dooley, Regenesis director of strategic projects.

“PlumeStop is going to coat the soil, so in essence we’re creating a ‘Brita’ filter underground,” Dooley explains. “As groundwater flows through this PlumeStop zone, the PFAS compounds are removed from the groundwater and sorbed onto the colloidal activated carbon, or the PlumeStop, and stabilized. Ultimately, it’s stabilized and stays in place and clean groundwater moves through the zone.”

Colloidal activated carbon barriers are designed to be a permanent solution and do not require later excavation of contaminated soil, Dooley says. “There is no requirement to excavate PFAS-impacted soils since it is the water phase that is the medium of concern,” she says. “In the remediation industry, it is common that soil contaminants are left in place if there is no risk to downgradient receptors…In the rare case where PFAS levels may exceed regulatory limits, the barrier can be reinforced if needed.”

Regenesis, based in San Clemente, California, has conducted 30 PlumeStop field applications for PFAS remediation since 2016, including nine at airports in the U.S., Canada, and the UK. Airports in the U.S. include Fairbanks International in Alaska and Grayling Army Airfield near Grayling, Michigan, where AFFF foam was used and stored.

PFAS remediation efforts at aviation sites have been more recent, says Dooley, who expects demand will increase as facility owners investigate contamination. PFAS contamination by FBOs and hangar owners would likely be the result of leaks or spillages of foam rather than of repeated firefighting drills, she says.

“It has come up around some hangars that they may have some small hot spots, but I wouldn’t anticipate it to be as extensive an individual problem as you might find in a fire-training location because of the multiple applications over time” at those locations, Dooley says.

Alternative ‘Destruction’ System

An alternative to the PlumeStop in situ approach to stemming PFAS migration is offered by nonprofit research and development organization Battelle, which has installed a “PFAS Annihilator” system at a wastewater treatment facility operated by Heritage-Crystal Clean in Wyoming, Michigan.

Described as a closed-loop, on-site destruction solution, PFAS Annihilator separates PFAS compounds from landfill leachate—water that has percolated through a landfill and accumulated contaminants—then uses supercritical water oxidation to break the carbon-fluorine bond. The resulting output, Battelle says, is carbon dioxide and hydrofluoric acid, which is neutralized with sodium hydroxide that turns it into inert salts. Ultimately, the water is sent to the treatment facility and returned to the water system.

In January, Battelle launched a spin-off company, Revive Environmental, at its Columbus, Ohio, campus to provide contaminant mitigation services using PFAS Annihilator and other technologies.

“While there is still uncertainty around the regulatory landscape and liabilities associated with PFAS, it is clear that commercial airports will be required to switch from PFAS-containing AFFF to fluorine-free alternatives approved by the FAA,” said Revive CEO David Trueba, in response to an inquiry. “In this transition, airports will have stockpiles of AFFF concentrate, AFFF-containing rinsewaters from changing out their foam systems, and potentially PFAS-contaminated groundwater from sites where AFFF was used.”

Trueba added: “Revive Environmental’s first PFAS Annihilator unit is commercially operating in Michigan and has already been destroying PFAS in different AFFF-contaminated waste streams. With more PFAS Annihilator units on the way this year, Revive is in conversations with airports and other industry partners to provide full lifecycle solutions that provide regulatory compliance and eliminate liability via PFAS destruction.”