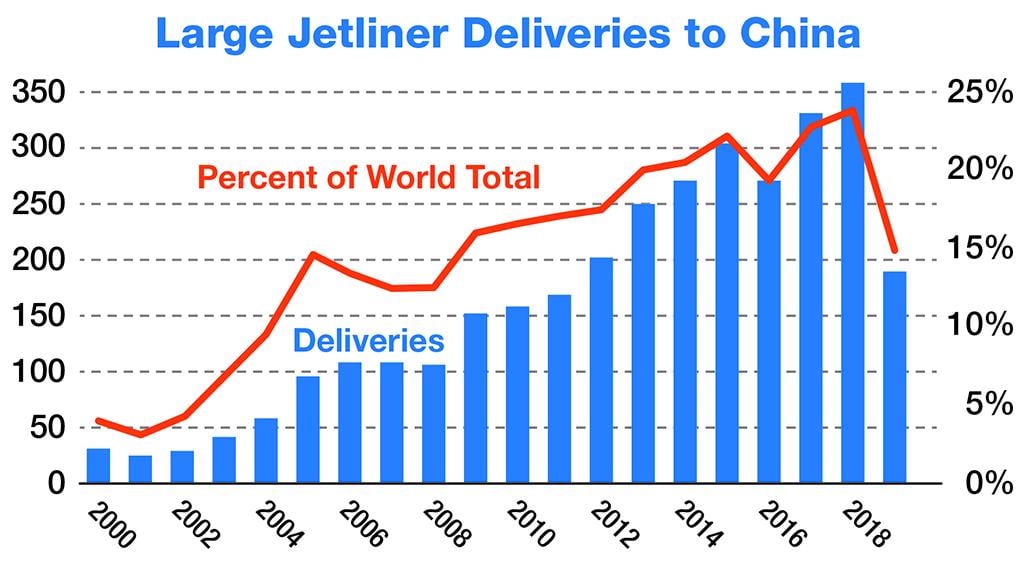

Jetliner market recoveries for the past few decades have greatly benefited from the rise of China, whose market was the only one that combined fast demand growth with sheer size. Over the past two decades, the country grew in importance to our industry, taking just 2% of total Airbus and Boeing output in 2001 and rising to a peak of 23% in 2018. The graph below indicates this dramatic increase in China’s importance to the market.

Our industry is clearly headed into a bust cycle, we hope to be followed by a recovery. But this time, the industry might find that post-coronavirus Chinese demand is not what it was before and that the recovery side of a V-shaped market downturn is a bit less steep. There are two reasons to be concerned.

First, China’s economic problems and its air traffic slowdown started months before COVID-19 was identified. Nominally, GDP growth last year was 6.1%, but there were plenty of indicators of a less robust reality. For example, car sales actually fell more than 8%. And according to the International Air Transport Association, China air travel demand fell from 12.2% year-over-year growth in late 2018 to just 5.3% by October and November 2019.

Typically, air travel demand for a fast-growth market like China is roughly twice GDP; that late-2018 12.2% figure is clearly supportive of 6.1% GDP growth, capping many years of double-digit growth. The single-digit growth in the second half of 2019 would be typical for an emerging economy growing at 2.5-3%.

China’s recent economic figures reflect a much worse reality. Its economy contracted in January and February for the first time in over half a century. Industrial production fell 13.5% from a year earlier. China domestic air travel in January fell by 6.8%, which was just the start of the COVID-19 impact.

Second, China’s jetliner market downturn started a year before COVID-19, in line with the country’s air travel demand drop. While 2018 saw a record of 355 jetliners delivered to Chinese customers, this was cut almost in half in 2019, to 180 jets. Some of this decrease was due to the cessation of Boeing 737 MAX deliveries. But Airbus did not exactly pick up the slack: Deliveries from Airbus fell 12% in 2019, despite a capacity expansion at the European company’s Tianjin A320 final assembly line.

Even before the coronavirus-related traffic collapse, scheduled deliveries in 2020 were slightly lower than 2019’s already low level. In relative and absolute terms, the China market has been halved, and given the coronavirus situation, it is quite likely that demand will fall further before it resumes growth, hopefully in the next few years. But it might not get back to the 2018 peak until 2023 or later.

The situation is not completely bleak. China can provide state aid for airlines and lessors more readily than most other countries, although that is just a stabilization measure. It is not the same as returning the country and its air travel industry to the remarkable growth track it was on as it transformed from a poor country to a middle-income one. In terms of its economy and its air travel market, China might be plateauing out.

This crisis has worsened China’s relations with the U.S. and the West, which were already getting bad. Looking beyond the post-coronavirus recovery, as economic nationalism increases and Western supply chains move away from China—and as state aid plays a bigger role in many economies (due to the coronavirus economic downturn)—China might pursue an increasingly autarkic future.

Building jetliners is already a priority in the country’s 2035 plan, and while the results so far have been poor, that problem could be solved with trade barriers. Chinese airlines would be forced, against their will, to buy local jets.

This bigger concern about China’s aviation future is more of a post-2030 problem. But for the coming few years, the important conclusion is that China likely will not play the same big role in a steep V-shaped recovery. The country probably will stay at a somewhat muted level of growth in its economy, air travel demand and the jetliner market even after the COVID-19 crisis passes. There might be a robust China traffic recovery, but we are unlikely to see the kind of strong, sustainable growth numbers that benefited the aviation industry for the last two decades.

Richard Aboulafia is vice president of analysis at Teal Group. He is based in Washington.

Comments