Despite some headline-making claims over the past decade, there are no instances on record of unauthorized entities accessing the flight controls of an airliner. But one cybersecurity company with an unusually deep interest in aviation says the sector’s embrace of digital technology is heading in a direction that might make hacking an airplane possible.

- Industry needs improved standards for electronic flight bag security

- Disclosures and collaboration can boost protection

The reason Pen Test Partners (PTP) focuses on aircraft cybersecurity is simple. “Three of us are pilots,” says Ken Munro, who founded the British company in 2010. “One of us had the bright idea to ring up a breaker’s yard and say: ‘Have you got anything that still works?’ They did, so we started learning.”

Four years after they first got their hands on a recently retired airliner, Munro and colleagues spent the first two days of Infosecurity Europe (InfoSec)—a major event on the UK’s cybersecurity calendar—holding presentations and panel discussions on aviation cybersecurity. The primary focus was on vulnerabilities introduced by electronic flight bags (EFB).

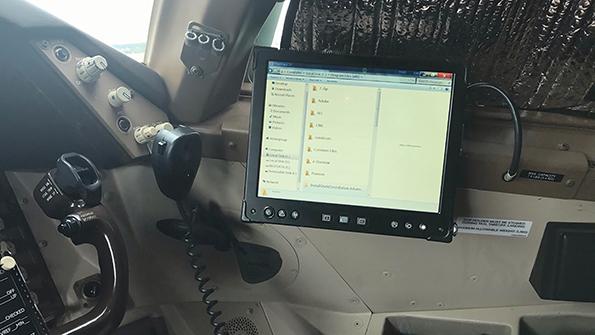

“An EFB is typically a tablet or a Windows device that’s usually taken home by the pilot,” Munro says. “Sometimes you see them physically bolted onto the cockpit. They’re a really, really good device for helping keep flights safe and efficient.”

Unfortunately, however, EFBs are slipping into a gray area in airline security protocols. A lack of consistent standardization on how to treat tablet- or laptop-based EFBs for security purposes introduces a host of disturbing potential new vulnerabilities, Munro and colleagues say.

“One common problem we see is an almost complete lack of hardening of those devices,” Munro says. “So an iPad, tablet or Windows device with no PIN [personal identification number], or a really simple PIN like “1-2-3-4” or the first four digits of the pilot’s birthday, which is easy to find. We see devices with no device lock, or we see devices that the pilots just go and buy themselves. They’re not updated, there’s no MDM [mobile device management].”

The potential consequences of an unsecured, or ineffectively secured, EFB run the gamut from surprising to terrifying. Real examples—not just on aircraft in a boneyard—include one EFB programming error that meant the device did not verify its content, potentially allowing an attacker to alter data in the EFB without the pilot’s knowledge, and a device with an easy-to-guess code permitting the same kind of manipulation.

“You could make the runway appear longer than it actually is,” Munro says. “So the performance calculator commands less thrust, and your plane goes off the end of the runway.”

PTP is keeping details of these vulnerabilities private while all concerned parties work to fix the problems. After two years of trying and failing to get a substantive response, however, PTP has gone public with its concerns over PilotView, an EFB system developed by Montreal-based CMC Electronics.

In CMC’s case, the EFB in question features a tablet that was fixed to the cockpit of a Boeing 747 in storage following the COVID-19 lockdowns—and since retired—but PTP believes similar installations are still in service. The device required a password to unlock it, but the password was “password.” Moreover, by pressing the control, shift and enter keys, PTP was able to exit the pilot application and access the underlying device operating system. The two EFBs in the cockpit were networked, and it was possible to compromise one device from the other.

“They had [the device’s] USB ports enabled, but of course it was safe because it had a sticker saying not to use the USB slots,” Munro says. “That made me chuckle.”

The decision to identify the vulnerable system publicly was not one that PTP took lightly. The company practices responsible disclosure, a process in which security researchers alert vendors to errors in code and give them sufficient time to develop and implement repairs before publishing details more widely.

Responsible disclosure is intended to make systems safer. The procedure allows vendors to address issues: Publication acts as a sector-wide information-sharing exercise as well as an incentive for vendors to field fixes in a timely manner. For safety-critical systems, the process is lengthier and more carefully coordinated.

“Because many of the systems are certified, fixing isn’t a matter of 90 days’ work,” Munro says. “We’ve got a vulnerability outstanding with an OEM that’s just coming up to two years since we first disclosed it to them. But the OEM was incredibly responsible and explained on Day 1 it was going to take at least a year to recertify the code, let alone do the fixes and push them out to the fleets. We’re just about to do coordinated disclosure with them where they’ve actually helped us write the publication.”

With CMC, the process was not so collaborative. “We’ve tried really hard to disclose this quietly,” Munro says. “But we’ve been ignored. Aviation cybersecurity groups helped us get in contact with CMC, which still ignored us. We asked the [aircraft] OEM if they could push a bit, and they tried. After another six months, we went back to the industry groups and said: ‘We’re thinking about disclosing this. What do you think? Is that acceptable?’ And they said: ‘Yeah, you’ve tried really hard. We think that’s reasonable.’ We did a briefing to industry first, so they had three months early warning of what we were going to say publicly.” CMC did not respond to a request for comment.

The issue goes to the heart of what PTP had hoped to get across to their cybersecurity audience during InfoSec. One area where the cybersecurity profession could perhaps learn from aviation is that sharing data about mishaps can help strengthen the entire community. But even in an industry familiar with practicing responsible disclosure, there remains a reluctance to share experiences that may be perceived as negative.

“One thing I love about aviation is we talk about our [mistakes],” Munro says. “Every time a plane crashes, there’s an investigation. And independently, without attribution, we find out what went wrong, and then we tell everyone else what went wrong as well. That’s unbelievably powerful.”

Yet aviation cybersecurity practitioners may not always share details of breaches when there is no requirement to do so and the nature of the problem does not threaten safety.

“If it’s an occurrence that has to be reported under regulation, people will report it,” said Kirsty Richardson, head of cybersecurity oversight at the UK Civil Aviation Authority, during a PTP-hosted panel discussion. “But my team struggles to get entities who suffered a cyberbreach to actually share their information with us, because they think as the regulator we’re going to come down hard on them.”

The answer, others suggest, is not technical or related to regulation but instead is a matter of institutional approach.

“It comes down to the culture of the people within the organization,” says Pete Cooper, a former military fighter pilot who is now deputy director of cyberdefense in the UK government’s Cabinet Office. “If the culture is a good culture, they’ll put their hand up and say: ‘Actually, I had a near miss,’ or ‘Something nearly happened.’ If you approach it like that, you can learn from it.”

Mary Haigh, BAE Systems’ chief information security officer, says: “A cybersystem is different [from] an airplane with a black box. It takes me quite a while to sort out what’s gone wrong in a huge enterprise network when it’s been breached, and I might never fully know everything. [At] BAE, we’ve been doing some exercises, and it definitely still isn’t in that space of ‘We’ll just understand what’s going on.’ It is in the space of ‘Whose fault was it?’ There is a massive amount of work we’ve got to do in the cyberindustry. We have to keep that openness, because the minute you start looking into blame, people start hiding stuff.”

And in aviation cybersecurity, the need is getting progressively more urgent. “We’re starting to see EFBs integrated automatically with flight management systems (FMS), which removes a layer of abstraction and cybersecurity,” Munro says. “If you’ve got a vulnerability in the EFB, you’ve now got problems in the FMS. The [Airbus] A350 already does this.

“The bit that really bothers me, though,” he adds, “is we were speaking to a chief pilot of a large airline, and he told me: ‘We encourage all our pilots to take their EFBs home and use them like a personal iPad. In fact, my child was watching Netflix on my EFB on the way to the airport yesterday.’ That really, really worries me, because these are safety-critical devices doing safety-critical calculations.”

Editor's Note: This story was updated to include the fact that CMC did not respond to a request for comment. It was further updated to add more nuance to the headline.