Final year-end figures show just 157 Boeing airliners were delivered in 2020, compared to 380 in 2019—revealing the full impact of the global COVID-19 pandemic and the prolonged grounding of the 737 MAX on the company’s commercial business.

Released as part of Boeing’s fourth quarter production statement, the tally includes 43 737s—31 of which were delivered in the final weeks of the year following the ungrounding of the MAX by the FAA in November 2020. The drop in 737 deliveries has been primarily responsible for the precipitous decrease in overall Boeing commercial deliveries over the past two years. These declined from a peak of 806 in 2018 to 380 in 2019, before sliding again to just 157 in 2020. Of the 2018 total, some 580 were 737 models while the small twinjet made up 127 of the 2019 total.

However, while deliveries of 737s are due to step up significantly in 2021 as previously completed aircraft are retrieved from storage and new production steps up, the delivery numbers also underline another potentially serious problem with the 787. Only 53 787s were delivered in 2020 compared to 145 in 2018 and 158 in 2019. Of 2020’s tally only four 787s were delivered in the last quarter amid on-going manufacturing issues and inspections.

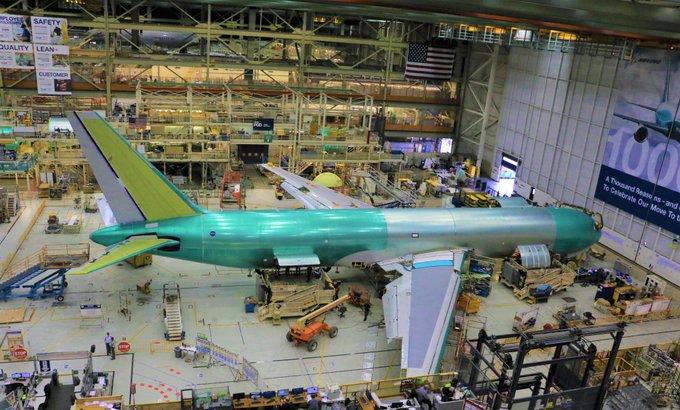

Commenting on the status of the program, which is in the midst of being transferred from Everett, Washington, to Boeing’s South Carolina facility, company CFO Greg Smith said “we also continued comprehensive inspections of our 787 airplanes to ensure they meet our highest quality standards prior to delivery. While limiting our 787 deliveries for the quarter, these comprehensive inspections represent our focus on safety, quality and transparency, and we’re confident that we’re taking the right steps for our customers and for the long-term health of the 787 program.”

But the smaller than expected delivery numbers for the last three months have taken industry watchers by surprise and some, such as analysts company Bernstein, suggest this may be a warning of worse news to come. In a recent note to investors the company says the “main 787 worry was long delivery delays could lead to repricing or substantial compensation. The second biggest concern was that there may be extensive costs to inspect and repair airplanes in the field. This is very uncertain.”

In other programs, two of Boeing’s commercial stalwarts, the 767 and 777, faired relatively better and provided the company with valuable income over the year. Although Boeing announced in 2020 that first deliveries of the 777X will be delayed to 2022, production of the 777 continues with freighter versions making up a significantly greater proportion of the annual total than in previous years. Of the 26 777s delivered in 2020 some 22 were freighters.

Bolstered by production of 767-300F freighter variants and the KC-46A military tanker, deliveries of the 767 hit 30 in 2020 compared to 43 in 2019 and 27 in 2018. The 747-8F, production of which is due to be phased out in 2022, also continued to be delivered at a slow rate with five handed over to UPS during the year of which three were in the last quarter. Overall Boeing delivered 46 freighter versions of the 767, 777 and 747-8, representing a record 40% of the overall 114 widebody deliveries made in 2020.

Boeing also ended the year with 4,223 aircraft in its backlog, down 22% since the end of 2019. This was due mainly to pandemic-related cancellations and accounting adjustments, and included cancellations made in December for 107 aircraft—of which 105 were for the MAX. Of the remaining backlog, 3,321 are 737s, eight are 747-8Fs, 75 are 767s, 350 are 777s and 469 are 787s.

Comments

The Airlines much preferred the -200 variant due to better range and lower turn-around times.

Also, even if the major assembly jigs and fixtures are still available, any re-engining and cockpit upgrade program would be costly.