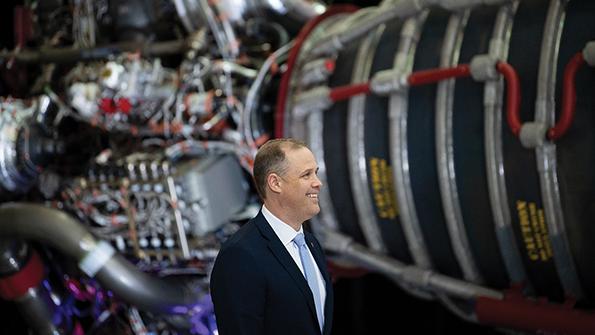

Jim Bridenstine, the ever-buoyant head of NASA, was almost giddy when he unveiled President Donald Trump’s budget request for the fiscal year beginning Oct. 1, which would hike the agency’s share of federal spending to more than $25.2 billion—about 12% more than its current allocation.

“This is one of [the] strongest budgets in NASA history. . . . It is up to us to deliver,” Bridenstine said during a televised address from NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi, where the core stage for the agency’s first Space Launch System (SLS) rocket is being prepared for a static engine firing later this year.

- Moon and Mars exploration are top nasa budget priorities

- The plan delays the SLS upgrade

The SLS is a key but expensive part of NASA’s plan to expand human presence beyond low Earth orbit, an initiative intended to lead to astronaut missions to Mars in the 2030s, following a series of expeditions to the lunar surface and establishment of a small outpost in lunar orbit under the Artemis program.

Although NASA has been largely spared from divisive and derisive partisan politics, it may be a hard sell—particularly during an election year—for Congress to buy in to a Trump-backed expedited Moon program that skeptics view as timed to coincide with his possible second term in office.

For example, in December, NASA received just $600 million of a requested $1 billion to start work on human-class lunar landers. Then in January, the space and aeronautics subcommittee of the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology passed a bipartisan bill that moves the 2024 lunar landing deadline to 2028, which was NASA’s original plan before Vice President Mike Pence last year told the agency to cut four years off the program.

Instead, the House version of the NASA Authorization Act of 2020 calls for the space agency to develop technologies and systems to put astronauts into orbit around Mars by 2033. It also repudiates NASA’s plan to develop the human lunar lander under partnering agreements and commercial flight service contracts.

“This bill is not about rejecting the Artemis program or delaying humans on the Moon until 2028,” subcommittee Chairwoman Rep. Kendra Horn (D-Okla.) said at the Jan. 29 hearing. Rather, it aims to take “the fiscally responsible approach of focusing the Moon efforts on the goal of being the first nation to set foot on Mars,” she said. “NASA can still work to safely get there sooner.”

Bridenstine, a former U.S. Representative from Oklahoma, and his team remain undaunted.

“Jim [Bridenstine] has created this [one-NASA] approach,” says Deputy Administrator Jim Morhard. “It’s a proven strategy that has gotten bipartisan support so far. . . . All parties should have full confidence that we’re continuing to move forward to the Moon.”

The fiscal 2021 budget request released Feb. 10 not only continues $4 billion annually for the long-delayed SLS, the Orion deep-space crew capsule and related ground-support systems—programs that already have consumed more than $34 billion—but also earmarks more than $3.3 billion to begin developing human-class landing systems, the long pole in the Trump administration’s call to return astronauts to the Moon in 2024.

Ultimately, the agency says it will need to spend $21.3 billion on human-class landers over the next five years, not including an undetermined amount from industry partners that have yet to be selected. Three companies confirmed they submitted proposals in November in response to a NASA Broad Agency Announcement to develop and demonstrate a Human Landing System (HLS). The contenders are: Boeing; Blue Origin, which is partnering with Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin and Draper Laboratory; and Dynetics—which on Jan. 31 became a wholly owned subsidiary of Leidos—partnering with Sierra Nevada Corp.

A fourth proposal is believed to have been submitted by SpaceX, but the company declined to comment. Two or more awards are expected in late March or early April, NASA noted on its procurement website on Feb. 10.

Under fiscal 2021-25 budget plans, the HLS would consume nearly two-thirds of the $35 billion NASA says it needs to stage a 2024 human mission to the Moon, the first crewed lunar landing since the end of the Apollo program in 1972.

The proposal, however, delays funding for a more powerful, four-engine upper stage for the SLS Block 1B configuration, intended to replace the single-engine Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage on the SLS Block 1. With one flight planned per year, NASA now pegs the cost of sustaining the SLS-Orion program at $2 billion annually, according to Brian Dewhurst, resource management officer for NASA’s Human Exploration and Operations division.

The launch date for the first SLS-Orion mission, an uncrewed trial run around the Moon, is under review.

NASA Budget Spotlights Exploration, Not Science

A big boost in spending for human exploration at NASA comes at a cost to the agency’s science programs, which would take a 12% cut under the budget proposed by President Donald Trump for the fiscal year beginning Oct. 1.

- Mission to map Mars ice proposed

- Budget plan shrinks science spending 12%

The spending plan, unveiled Feb. 10, includes a third attempt at canceling the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (Wfirst), a companion to the James Webb Space Telescope for the exploration of dark energy and the search for chemical biosignatures in the atmospheres of planets beyond the Solar System. Congress has consistently restored funding for Wfirst, as well as for the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy that the White House again seeks to cancel.

Trump’s budget request of $25.2 billion for NASA—a 12% hike over current levels—includes $6.3 billion for science, an $832.4 million, or 11.6%, reduction from current spending.

The plan includes funding to begin the Mars Sample-Return and Mars Ice Mapper missions. The sample-return initiative, a cooperative effort with the European Space Agency that is planned for a 2026 launch, would follow the Mars 2020 rover scheduled to launch this summer. The rover is expected to reach Jezero Crater, an ancient lake and river delta on Mars, in February 2021 to seek out evidence of past habitable environments as well as to gather and cache samples of rocks and soil for return to Earth.

The sample-return mission would feature a lander and robot-arm-equipped rover to collect the Mars 2020 rover samples, the first-ever rocket to launch from the Martian surface and a Mars orbiter to stow the samples for a return to Earth, perhaps by 2031.

The 2021 NASA science budget proposal seeks $232.6 million to advance work on the Sample-Return and Ice Mapper missions, with spending to rise to $775 million by fiscal 2025.

Other features of the 2021 NASA science budget proposal include continued development of the Europa Clipper, a mission to conduct a succession of close flybys of the ocean-bearing moon of Jupiter to further assess its potential for life. Congress wants NASA to launch the Clipper on the Space Launch System, which would shave 3.5 years off its journey but cost an extra $1.5 billion over commercial alternatives.

Overall NASA science spending would increase but would not return to the 2020 level through fiscal 2025, budget documents show.

—Mark Carreau in Houston

Aeronautics Budget Advances Electrified Aircraft Propulsion Focus

NASA plans to launch an electric propulsion X-plane program in fiscal 2021 as a follow-on to the X-59A QueSTT low-boom supersonic flight demonstrator, which is now scheduled to fly by January 2022.

- Electrified powertrain flight demonstration planned

- Increased emphasis on urban air mobility

Funding to begin the Electrified Powertrain Flight Demonstration (EPFD) project is included in the $819 million sought for aeronautics research in 2021, an increase of 4.5% over the funding enacted for 2020.

But the 2021 request moves $117 million in funding for ground-test capabilities such as wind tunnels back under the Aeronautics Mission Research Directorate. Excluding this accounting change, funding requested for NASA’s other aeronautics programs is reduced to $702 million.

Funding sought for 2021 would complete preparations to fly the Lockheed Martin Skunk Works-built X-59 and to fly the X-57 Maxwell distributed electric propulsion demonstrator in its final, Mod 4, form with a new optimized wing with wingtip cruise propulsors and leading-edge high-lift propellers. The X-57 is scheduled to make its first flight this year.

Also in 2021, the Advanced Air Mobility project is to move from the Airspace Operations and Safety Program to the Integrated Aviation Systems Program, so as to manage large complex flight demonstrations beginning with NASA’s Urban Air Mobility Grand Challenge.

In preparation for the EPFD project, the Advanced Air Vehicles Program plans in 2021 to conduct ground-testing of a flight-weight megawatt-class electric inverter under simulated 30,000-ft.-altitude conditions in the NASA Electric Aircraft Testbed. It will also complete the critical design review on a project to demonstrate large-scale power extraction from the high- and low-pressure spools of a turbofan.

—Graham Warwick in Washington

Comments