While commercial aircraft are careful to avoid flying over conflict areas, airlines are increasingly confronting a dangerous spillover from war zones—spoofing. The practice involves state and non-state actors transmitting fake global positioning system (GPS) signals that can confuse and mislead pilots.

Spoofing is largely intended by both state and non-state actors to misdirect military aircraft and drones in war zones. But the fake signals, which are widely transmitted, often end up affecting navigation systems in commercial aircraft cockpits.

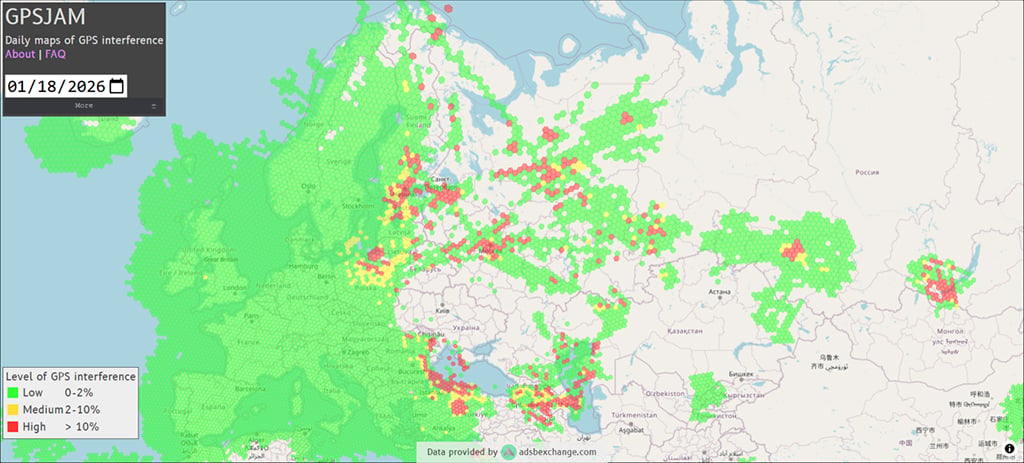

Spoofing was generally not a problem for airlines before Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, which sparked a full-scale war in Eastern Europe where spoofing—especially aimed at misdirecting drones—first became prominent. But over the past four years, spoofing has spread exponentially around the world, first to the Middle East and then elsewhere, and become a major safety concern for commercial aircraft.

“Spoofing is being used more and more in conflicts,” Ben Mohr, Honeywell Aerospace’s offering director for alternative navigation products, told ATW. “This has implications, obviously, for defense users. But it also has implications for commercial users because these signals don’t necessarily respect boundaries. They spill over large areas. State-owned spoofing systems are very, very powerful and have a very long range. There are also pretty inexpensive systems that non-state actors have access to as well. So, there’s a wide variety of threats out there. It’s a growing problem for both the defense and commercial aviation communities.”

OpsGroup, a membership organization comprising pilots, flight dispatchers, schedulers and controllers, brought together a working group of flight deck crew, air traffic controllers, regulatory authorities, aircraft manufacturers and GPS experts to develop a comprehensive report on spoofing in 2024. The GPS Spoofing Working Group’s final report concluded that the danger to civil aircraft is “extremely significant.”

“Because modern aircraft have incorporated GPS into a large number of aircraft systems, the impact of a spoofed GPS signal has had severe and cascading effects,” the report concluded, adding: “Since satellite signals are very low power, the spoofed GPS signal overpowers these quite easily. The aircraft GPS receiver now takes the fake signal as true and begins to share the new false position with aircraft systems.”

The false information “typically includes a false position (wrong coordinates), false date and time, false altitude and often false system settings,” the report stated.

Simon Innocent, Honeywell’s senior director offering management for commercial navigation systems, noted EASA reported 6,000 spoofing events in 2024, “of which 25% were during approach.”

“Actual occurrences are believed to be 50 times more frequent than reported,” he told ATW, adding that “spoofing can affect approach and departure operations in the terminal area around airports, where traffic is particularly dense. As flight crews detect abnormal behavior of aircraft systems, the number of go-arounds and missed approaches increases and can lead to infringement of aircraft separation, especially if air traffic control monitoring capabilities are impaired by incorrect ADS-B data.”

SPREADING PROBLEM

The problem is no longer contained within Eastern Europe and the Middle East, where spoofing has been most acute and grown rampantly since 2022. There were reports of spoofing in Caribbean airspace near Venezuela in late 2025 and in India throughout 2024 and 2025. ICAO felt it necessary to issue a North Atlantic Operations Bulletin on navigation system interference in early 2025.

“Aligned with reports in other regions, since February 2022 the [North Atlantic] has seen an increase in the frequency and severity of the impact caused by … jamming and/or spoofing as well as an overall growth of intensity and sophistication of the events,” ICAO stated. The spoofing usually occurs before aircraft enter North Atlantic airspace, but “the inability of the aircraft to recover in-flight leads to increased workload for both flight crews and air traffic controllers in the [North Atlantic],” ICAO stated.

“Long-haul operators are reporting that almost 100% of flights from Europe to eastern destinations [Asia-Pacific and the Middle East] encounter GPS radio frequency interference,” Innocent said.

He warned that the problem may move beyond commercial aircraft being affected by spoofing intended for military aircraft and drones. “Given the rapid evolution in spoofer capabilities, regulators and operators [need to] also consider that the [airline] industry must prepare for scenarios where malicious state or non-state actors would use advanced, targeted spoofers to take an aircraft off course,” Innocent said.

Jamming has long been a problem in aviation, but it is more easily detected than spoofing because it causes a GPS signal loss that becomes obvious to pilots. “The challenge [in detecting spoofing] is that pilots may not see anything different,” Mohr explained. “That’s what’s scary about spoofing versus jamming. Jamming is a much more straightforward attack. It’s just GPS denial. So, what a jamming attack looks like from pilots’ perspective is you lose GPS, which is not the end of the world on a commercial aircraft. You generally have an inertial navigation system which can operate just fine without GPS for quite extended periods of time. Spoofing is a little bit scarier because your system may not know it’s being spoofed, so you will get this misleading information, but there may not be an indication in the cockpit that there’s a problem.”

FINDING SOLUTIONS

Honeywell Aerospace and other aviation technology firms are scrambling to develop capabilities to counter spoofing. “Honeywell continues to develop advanced inertial systems, anti-spoofing receivers, surveillance systems resilience, smart antennas and multi-sensor fusion solutions to detect, mitigate and recover from GPS jamming and spoofing,” Innocent said.

Flight operations software solution provider Aircraft Performance Group (APG) said in a recent blog post on its website that receiver autonomous integrity monitoring (RAIM) “is a built-in safety net in many GPS receivers which uses redundant satellite measurements to check consistency and alert pilots if positional errors exceed predefined tolerances. RAIM helps detect signal anomalies caused by both natural errors and some spoofing attempts.” But APG noted that “sophisticated spoofing attacks that replicate legitimate satellite geometry can sometimes evade basic RAIM detection, highlighting the need for more advanced anti-spoofing measures.”

APG said the most effective current defense involves “integrating multiple navigation data sources rather than relying on GPS alone.” Inertial navigation systems “provide independent position updates that cannot be spoofed in the same way as [GPS] … Ground-based beacons can serve as a reliable cross-reference, especially in terminal environments … These cross-checks give pilots and dispatchers critical tools to identify inconsistencies that could indicate spoofing.”

IATA has flagged this issue, calling for global coordination involving airlines, air navigation service providers, aircraft OEMs and technology providers to address spoofing and develop mitigation strategies. The organization has also urged governments to preserve ground-based radio navigation systems as a backup to GPS.

The OpsGroup report noted “the industry trend has been to move away from ground-based navaids as much as possible. However, in light of the exposure of GPS vulnerability, a reverse in this approach is needed.”

The GPS Spoofing Working Group concluded “there are no easy overall solutions. While mitigations can provide some temporary relief from the spoofing issue, longer term solutions to solving the problem are critical. Consideration must also be given to the potential for a deepening of the GPS vulnerability problem … Locations of interference could widen, and impacts could worsen.”