As the U.S. descended into one of its darkest chapters in recent history, with more than 100,00 Americans dead from the COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment levels not seen since the Great Depression of the 1930s and widespread protests over police brutality and racism, NASA kicked off a space mission that may become as iconic as the Apollo Moon landing more than 50 years ago.

The success of the new endeavor will be measured not only by its technological achievement—namely restoring U.S. capability to launch astronauts into orbit—but also by its endurance. By partnering with private companies, NASA seeks to build human exploration and space transportation programs that, unlike Apollo, never end.

- SpaceX Demo-2 paves way for operational flights

- Boeing aims for crew flight test in 2021

Toward that goal, NASA found kindred spirits in two distinct industries: the fast-paced tech world enshrined by SpaceX and the steadfast aerospace domain of Boeing. Bolstered by about $8 billion of taxpayer money, the companies took the lead in designing, developing, testing and ultimately flying low-Earth-orbit (LEO) transportation systems for astronauts and other travelers.

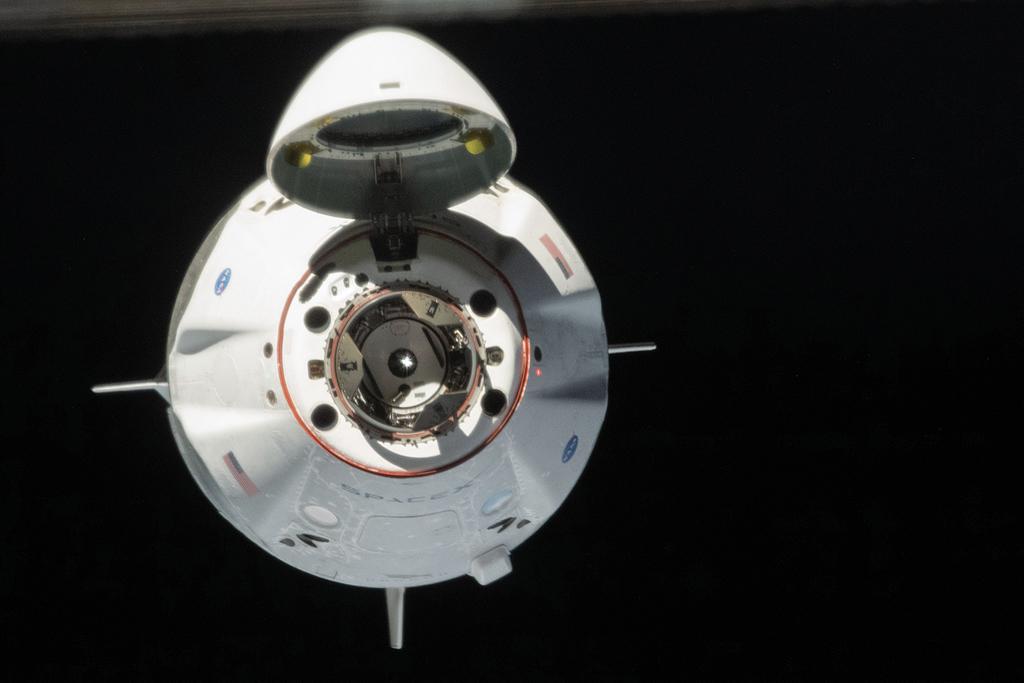

The SpaceX solution is attached to the International Space Station (ISS) now, having reached the milestone of a crewed flight test well ahead of Boeing. SpaceX’s May 30 launch of NASA astronauts Douglas Hurley and Robert Behnken on a Falcon 9 rocket marked the first orbital launch of humans by a private company and the first launch of astronauts aboard a U.S. spaceship since the space shuttle program ended in 2011.

“It’s a little hard to process at this point,” SpaceX founder, CEO and Chief Engineer Elon Musk said after the launch. “It’s difficult to come up with cohesive sentences that make any sense. . . . It’s just ‘wow.’" (AW&ST June 1-14, p. 56)

“This is hopefully the first step on a journey toward a civilization on Mars and life becoming multiplanetary for the first time time in the 4.5 billion year history of Earth,” Musk adds.

If the ongoing Demonstration Mission-2 (Demo-2) is successful, SpaceX could be ready to fly its first long-duration crew rotation mission on Aug. 30.

“We’re at the dawn of a new age, the beginning of a space revolution,” says NASA Deputy Administrator Jim Morhard. “This is really something much bigger than all of us. Our hope and prayer is to inspire the next generation, give hope for many people who need it right now and unite our country and the world.”

It is a testament to the preparation of the joint NASA-SpaceX team that in the days leading up to the Falcon 9’s 3:22 p.m. EDT liftoff on May 30, the primary concern was the weather. Florida’s fickle summertime storm cycle this year started early, dashing plans for an initial launch attempt on May 27. With the potential for rocket-triggered lightning in the skies around Cape Canaveral, the Demo-2 countdown was halted with 16 min. 53 sec. left on the clock.

“It is good for the agency to have a wet dress rehearsal behind us,” NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine said on May 29. “Every time we do one step, we learn things.”

The scrub provided the first demonstration—albeit an unplanned one—of what was once a highly controversial plan to fuel the booster with 1.2 million lb. of superchilled rocket-grade kerosene and liquid oxygen after the astronauts were strapped inside the Crew Dragon capsule perched on the rocket’s nose.

The procedure, known as “load and go,” was once a showstopper for NASA’s Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP). The space shuttles’ three liquid-fueled main engines were fueled before astronauts arrived at the launchpad.

“Hearing the venting and the valve sounds and the little vibrations associated with the fueling operation was a new experience for us,” Behnken told reporters during an inflight press conference on June 1.

NASA’s safety oversight board also delved into SpaceX’s use of an autonomous flight termination system on the Falcon 9, among other issues. Traditionally, the responsibility for triggering destruction of a wayward booster rests in the hands of a range safety officer on the ground.

“SpaceX and Boeing are very different in terms of how they approach systems engineering and integration,” ASAP member George Nield tells Aviation Week. “The traditional approach is [to] do lots and lots of analysis until you’re very confident that everything is going to work as you laid it out.”

SpaceX has a more agile process, which is to build something, test it and if it does not work as expected, change it, says Nield. “It can be very frustrating and scary for people used to the other approach because a typical engineer will want to lock down the design right at the beginning and then not change anything going forward.”

The traditional approach makes components and systems easier to track since approved designs stay the same. But Nield notes it also “locks you into whatever level of safety—or unsafety—that that system has.”

The SpaceX way presented a challenge for NASA as it tried to assess the robustness of the company’s systems engineering and integration.

“They came up with something that’s really impressive, frankly—a software program they call a ‘bill of design’ system, which is used for all aspects of the manufacture, the workflow process and the verification review,” says Nield, the former head of the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation, which will be licensing the space taxis after they have been certified by NASA.

“Everything is online, so somebody in a certain shift can see what happened in the last shift,” says Nield. “It’s all tied together through the component drawings, notes and production procedures. And it’s all automated so when you get to the end, you can see when this test was done and what the results were, how changing a particular valve has an impact on this other system.”

In addition, the system automatically catches deviations, such as human error in data entry.

“Boy, when some of the longtime NASA managers hear about these things, they’re just drooling because they had nothing like that in the era of the shuttle,” says Nield. “Everything was manual and on paper. It was very difficult to understand what the impacts of all the various systems were and how to quickly make a change that would roll downhill through all the other systems that were involved.

“It took a while to deploy [the SpaceX system], understand it and implement completely, but now that it’s being used, it is certainly an impressive system,” he adds. “They have given NASA almost complete access to that system so they don’t even have to be standing here looking over every component being installed or watching every test, because they can go in and check what the status is and understand what the impacts of a particular test are by just questioning that software system.”

The harmonic convergence of NASA and SpaceX will be tested throughout the ongoing Demo-2 mission, laying the foundation for cooperation on the Trump administration’s signature space initiative, Artemis, and its goal to land two U.S. astronauts—specifically a man and a woman—on the south pole of the Moon in 2024.

About the only surprise from the Demo-2 mission so far was the crew’s unexpectedly sporty ride to orbit on the Falcon 9’s upper stage, powered by a single Merlin 1D vacuum engine.

“It was a smoother first stage, a little rougher second stage than we saw on the shuttle,” says Behnken, the Demo-2 joint operations commander.

“The shuttle had solid rocket boosters to start with, and those burned very rough for the first 2.5 min.,” adds Hurley, Crew Dragon commander. “The first stage with Falcon 9, with the nine [liquid-fueled] Merlin engines and roughly the same amount of time, was a much smoother ride.

When nerves and apprehension turn into exhilarating pride. #crewdragon #endeavour #falcon9 pic.twitter.com/7fA3pfrMdw

— Karen L. Nyberg (@AstroKarenN) June 1, 2020

“Where the differences started . . . was at staging,” he continues. “The first-stage engine shut off, and then it takes a second between the booster separating and the Merlin vacuum engine starting. At that point, we go from roughly 3g to 0g in half a second, probably. Then when that Merlin vacuum fires, we start accelerating again for the next 5-6 min. until we achieve orbit.

“It’ll be interesting to talk to the SpaceX folks to find out why it was a little bit rougher ride on the second stage than it was for the shuttle on those three main engines,” Hurley adds.

SpaceX’s capsule is designed to fly autonomously, but Hurley and Behnken had two opportunities before reaching the ISS to input manual controls, via touch screens, and test the Dragon’s handling characteristics. “It flew very well, very crisp . . . just about like the simulators,” Hurley radioed to dual Mission Control Centers at SpaceX headquarters in Hawthorne, California, and at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. “It’s been a spectacular spaceship so far,” he noted on Twitter.

NASA has been preparing for a new chapter in human space exploration since the Columbia Accident Investigation Board in 2003 called for the retirement of the space shuttles as soon as ISS assembly was complete. Initially, the agency planned to have its Orion deep-space capsule, in development since 2006, to double as an ISS crew transport.

But facing budgets that would not support both LEO and deep-space transportation initiatives, the agency began mulling whether the commercial partnering agreements established under the George W. Bush administration to fly cargo to the ISS in the post-shuttle era could be a model for transporting astronauts as well.

In 2010, during the Obama administration, NASA launched the Commercial Crew Development program, aiming not only to save money and provide a U.S. alternative to the Russian Soyuz crew transport system but also seed a new industry for commercial space travel.

“The Commercial Crew program has been a great experiment by NASA to see if commercial companies can do this particular job,” says former shuttle program manager Wayne Hale, now a consultant at Special Aerospace Services.

The verdict should be in later this year. Hurley and Behnken transferred to the ongoing Expedition 63 crew, which is short-staffed due to U.S. paid rides on Soyuz coming to an end. The flight readiness of SpaceX’s next Crew Dragon will drive how long the Demo-2 mission lasts.

The capsule, which the crew named Endeavour after the retired space shuttle that hosted both astronauts’ first flights, is designed to remain in orbit for up to 119 days. Operational vehicles will remain docked to the ISS for six months.

What the U.S. will be like when Hurley and Behnken return is uncertain. Amid ongoing political and economic turmoil, peaceful and not-so-peaceful demonstrations and a deadly virus that has yet to be stemmed, NASA is pressing for a 12% budget hike for the fiscal year beginning Oct. 1 to $25.2 billion in an attempt to pull off a crewed lunar landing in 2024.

The parallels to the social unrest and violence of the 1960s and ’70s, which became a backdrop for the Apollo Moon landings, and present day are eerily similar. “We have had moments in American history where we have had challenges as a nation,” Bridenstine told reporters after the Demo-2 launch. “We think back to the 1960s with the Vietnam War, the civil rights abuses and the civil rights protests. We think about the height of the Cold War. And yet we had this moment in time—July 20, 1969—when all of America stopped, literally just stopped, because we had American astronauts walking on the surface of the Moon. And then we repeated that five more times.

“The Apollo program eventually ended, but what is great about NASA is that we bring people together. Everybody loves exploration; it’s unifying,” Bridenstine continued. “I am hoping that people can see this as something bright and hopeful and that people know tomorrow is a new day, a better day, and we’re always going to strive to do better.”