With seven NASA centers shuttered, the U.S. space agency is reassessing every program in its portfolio in light of employee safety amid the growing threat from the highly contagious COVID-19, which has infected more than 512,000 people worldwide and more than 76,500 in the U.S. as of March 26.

Among the earliest programs to be mothballed was the seemingly unstoppable Space Launch System (SLS) program. Prime contractor Boeing overcame all kinds of adversity over the last nine years to develop and deliver the first SLS core stage to NASA for testing, but now the program is stopped dead in its tracks.

- SLS static test fire on hold

- Work continues on Mars 2020 rover

NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine suspended work on the SLS and Orion deep-space capsule at the agency’s Michoud Assembly Facility, located outside New Orleans, and the Stennis Space Center in southern Mississippi, effective March 20.

With the number of novel coronavirus cases rising in both communities—and the first confirmed case of the disease at Michoud—Bridenstine closed the centers to all personnel except those needed to protect life and critical infrastructure. Access to NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, California, was similarly restricted on March 17.

A week later, the shutdown list had expanded to include Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland and Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, as well as the Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York.

The Glenn-operated Plum Brook Station in nearby Sandusky, Ohio, stayed open long enough to ship out the Orion spacecraft earmarked for a lunar flyby flight test in 2021. The capsule, built by Lockheed Martin, completed four months of thermal vacuum and electromagnetic environment testing at Plum Brook and arrived at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida on March 25.

Kennedy, NASA headquarters in Washington and the rest of the agency’s field sites remained open for mission-critical personnel as of March 26. Those facilities include: the Johnson Space Center in Houston; Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California; Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama; Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia; and White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico.

The Orion capsule may have an extended stay in Florida. The SLS rocket expected to launch Orion on a flight test around the Moon was finally shipped from its Michoud manufacturing facility to Stennis for integrated testing in January, following two years of delays to resolve technical problems.

A full-duration static test firing of the core’s four RS-25 engines, now on hold, was scheduled for this summer. The “Green Run” test campaign had been approaching avionics power-on, SLS prime contractor Boeing writes in an email to Aviation Week.

Still to come before the SLS hot-fire test are a countdown demonstration and wet dress rehearsal.

Completion of the Green Run sets the stage for SLS’ long-awaited flight test, a mission now known as Artemis 1 that will send an uncrewed Orion capsule around the Moon. Originally targeted for 2017, SLS’ debut was delayed to 2019 and, most recently, to November 2020.

However, even before Michoud and Stennis were shuttered due to COVID-19 concerns, NASA was not going to make the 2020 launch date. The agency in April had planned to announce a new target launch date for Artemis 1 of mid-to-late 2021.

“We realize there will be impacts to NASA missions,” Bridenstine said in a statement announcing the Michoud and Stennis closures. “But as our teams work to analyze the full picture and reduce risks, we understand that our top priority is the health and safety of the NASA workforce.”

Current plans call for Artemis 1 to be followed in 2022-23 by Artemis 2, a crewed flight test around the Moon, and in 2024 by Artemis 3, which would land astronauts on the south pole of the Moon. The expedited schedule to land on the Moon was set by President Donald Trump in March 2019.

NASA and Boeing are negotiating a production contract covering 10 more SLS cores for missions beginning with the Artemis 3 Moon landing.

The core stage for Artemis 2, currently under construction at Michoud, is part of Boeing’s original development and production contract—work that NASA’s Office of Inspector General estimates will have cost the agency more than $17 billion through the end of fiscal 2020, a March 10 audit shows.

NASA in October 2019 authorized Boeing to purchase long-lead materials and parts needed for Artemis 3, but the company does not yet have authorization to begin assembly. Boeing is aiming to establish a supply chain and a production line using its existing tooling to produce a core stage about every eight months.

The engine section, intertank, liquid oxygen tank, liquid hydrogen tank and forward skirt structures for Core Stage 2, which was due for completion in spring 2022, have been welded and built, says Boeing spokesman Jerry Drelling.

Meanwhile, in September 2019 Lockheed Martin, the prime contractor for Orion, signed a $4.6 billion production and operations contract with NASA covering manufacturing of six more spacecraft at Michoud. That work is now suspended.

The first Orion capsule was built under a $7 billion development and production contract. Including funds spent on Orion during the predecessor 2006-11 Constellation program, NASA budget figures show the project will have cost $18.5 billion by the end of fiscal 2020.

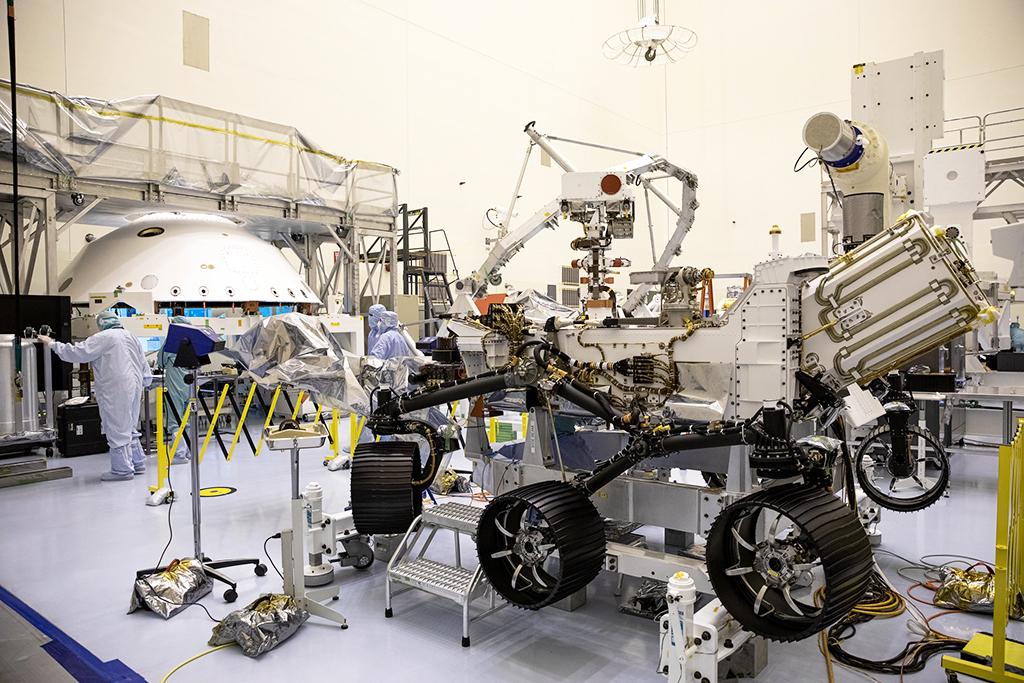

In addition to processing the first Orion spacecraft, Kennedy Space Center personnel are continuing to work on the Commercial Crew and Commercial Resupply Services programs in support of the International Space Station. NASA also is continuing to process the Mars 2020 rover at Kennedy for launch this summer. The opportunity to launch to Mars, which occurs every 26 months, is from July 17-Aug. 5.

“Mars 2020 is one of only two missions within SMD [Science Mission Directorate] that is the highest priority,” Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, said at a March 19 town hall meeting. The forum was held virtually due to cancellation of the annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference in Houston.

“As of right now—and even if we go to a next stage of alert—Mars 2020 is moving forward on schedule, and everything so far is very well on track,” Glaze said. “We’re also making sure that our personnel are healthy and safe.”

NASA’s other high-priority science mission was the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), due to launch in 2021 from the European Space Agency’s spaceport in Kourou, French Guiana.

France on March 16 suspended launch campaigns from the Guiana Space Center due to the COVID-19 pandemic. On March 20, NASA suspended work on JWST, which is located at prime contractor Northrop Grumman’s facilities in Redondo Beach, California.

Northrop, as well as other aerospace companies designated essential suppliers, are exempt from the state’s mandatory shelter-in-place orders intended to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus and COVID-19.

However, NASA said it could not ensure its employees and contractors could safely and effectively work under current social distancing protocols, which prohibit many people gathering in a tight place. Based on that assessment, NASA curtailed work on JWST on March 20.

“For most of the missions, there is nobody working hands-on anymore at NASA facilities,” says NASA chief scientist Thomas Zurbuchen.