An aircraft’s avionics system involves complex repairs, and dealing with a multitude of electronic areas—from an aircraft’s navigation system to its onboard communications—requires a sophisticated and varied skillset. Mechanics are no longer dealing with just nuts and bolts; maintaining newer-generation aircraft underpinned by advanced software demands experience with electronics and digital systems as well.

Sourcing labor has proved challenging for the MRO industry, including recruiting the right sort of technically efficient specialist to oversee avionics repairs. For U.S.-based avionics repair provider Avionics Specialist, for instance, recruiting technicians with the right capabilities is a tricky proposition.

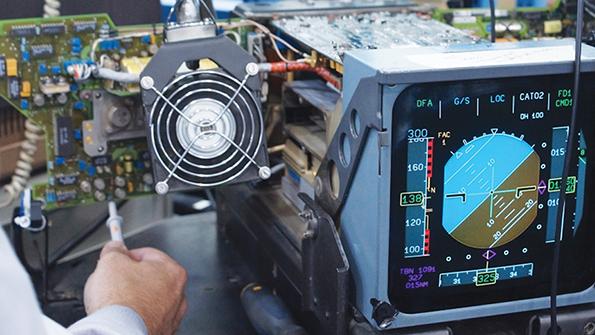

About 70% of the company’s business is commercial and military aircraft avionics. This consists of direct airline business, used equipment dealers, military and government subcontractors. The company has more than 50 technicians working on several avionics areas including communications, navigation, pulse, autopilots, antennas, wiring harnesses and metrology, along with a test equipment manufacturing department.

Wendell Law, the company’s director of technical services, puts the industry’s labor challenges down to several factors. “The lack of component-level electronics curriculum in the colleges along with the age of the most common electronics in the air transport fleet do not align,” he says. Law foresees demand for avionics repair specialists increasing due to the nature of newer aircraft types entering the market. “The newer avionics comprise so much more in software versus the older avionics,” he notes.

Recruitment of technicians with these avionics skills is also a challenge for AJW Technique, the Montreal, Canada-based MRO division of AJW Group. AJW Technique performs repairs on avionics that require an extensive electronics knowledge and understanding of avionics operations. “This is a rare skillset on the market, and very few aerospace training schools tend to focus on avionics,” says Sajedah Rustom, chief executive of AJW Technique. “It takes an average of 3-6 months of pure training to get an avionics technician up to speed on a select few units,” she says.

As it is difficult to find avionics specialists, Rustom says AJW Technique normally broadens its search criteria and looks outside the traditional aviation technician training schools. “We tend to go for general electronic and radio technicians, for example, which provide a base skillset, and we then develop technicians through our internal training programs into avionics technicians.”

Over the past three years, the company has ramped up from 15 to 30 technicians to accommodate increased demand for avionics services. “We follow a buddy program, which allows us to pair a younger technician with a more experienced counterpart and continuously develop our technicians through mentoring programs,” she says.

Naturally, this demand has opened opportunities for training providers. The British School of Aviation (BSA), established in late 2019 to aid efforts to help the training of MRO technicians and aircraft pilots, offers a short course revision training program for existing aviation professionals. “There will likely already be mechanics seeking to gain their [European Union Aviation Safety Agency] B2 avionics license,” says Ram Naidoo, who oversees some of the training courses at the BSA.

For the younger generation entering the workforce, Naidoo says the preference is for graduates to have combined mechanical and electrical engineering skills. “These days, the trend is to combine the B1 and B2 type training together—combining mechanical training with avionics training,” he says. “This is due to how modern aircraft are designed now, albeit the licensing is carried out separately.”

Naidoo believes aviation learning has changed. The younger elements of the MRO workforce are more naturally savvy with technology, and it is this, along with the technical makeup of aircraft that will drive this change forward long-term. “The way older aircraft were, even including older variants of the Boeing 737, 757 and 777, meant dedicated mechanical and avionics people were required. But it’s integrated engineering these days,” he says.