A strong heavy maintenance market is projected to moderate in the coming years as demand for major airframe checks returns to a more historical norm, but industry will be watching a few key trends that could affect near-term aircraft usage and, by extension, aftermarket activity.

Aviation Week’s 2020 Commercial MRO forecast sees the airframe maintenance market for the global, Western-built fleet of 33,700 aircraft certified for 10 or more seats increasing at an average compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.7% through 2029. The figure is slightly below the overall MRO market’s 2.9% projected average CAGR over the next decade, which is projected to start with annual rates closer to the mid-single digits.

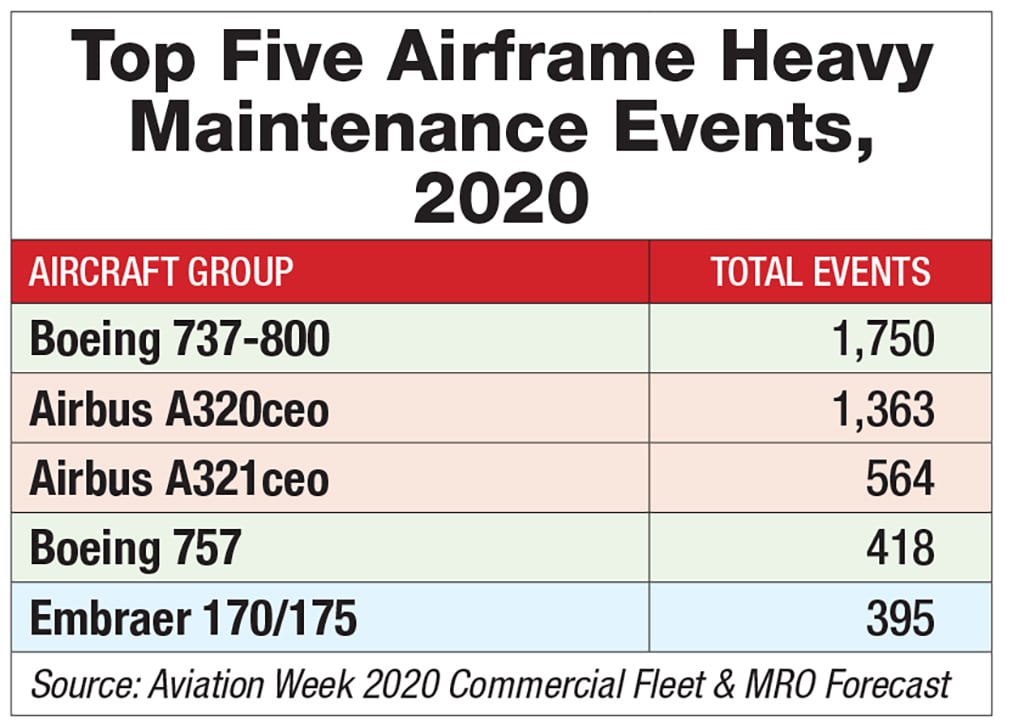

The fleet in 2020 is expected to generate nearly 10,600 airframe maintenance events, defined as C or D checks or the equivalent in phased inspections, and $4.9 billion in revenue. Not surprisingly, the two workhorse narrowbody models, the 737-800 and A320ceo, will generate the most 2020 activity. The venerable Boeing twin will account for 1,750 airframe events, while the baseline A320 model will undergo 1,363, the forecast shows.

- Airframe work projected to grow 2.7% annually

- 737 MAX’s return, fuel prices will affect near-term demand

The 2020 forecast combined with market intelligence suggests a deceleration before the market returns to a steady historical growth pattern. The heavy airframe maintenance market was particularly strong in 2019, lifted in part by demand for freighter conversions—particularly 737s and 767s. A Canaccord Genuity survey of about 40 aftermarket providers reported airframe heavy maintenance demand running 8% above year-earlier levels through the first half of 2019, and projected a full-year increase of 9%—in line with the MRO market as a whole. Looking ahead, respondents foresee growth slowing to 5% in 2020 for both the airframe and total MRO markets.

A decline in heavy checks would go hand-in-hand with upticks in both retirements and deliveries. Retirements have been trending below recent historical averages, falling to 1-2% of the in-service fleet, thanks to a combination of sustained strong demand for lift and issues with new airframe and engine programs that have slowed deliveries. Aviation Week sees commercial retirements rising in each of the next four years to approach 1,200 in 2023—more than twice the expected final 2019 figure.

A decline in heavy checks would go hand-in-hand with upticks in both retirements and deliveries. Retirements have been trending below recent historical averages, falling to 1-2% of the in-service fleet, thanks to a combination of sustained strong demand for lift and issues with new airframe and engine programs that have slowed deliveries. Aviation Week sees commercial retirements rising in each of the next four years to approach 1,200 in 2023—more than twice the expected final 2019 figure.

The Boeing 737 MAX is the most prominent example of new-program issues affecting fleet plans. As 2019 headed into 2020, airlines were making up for not having some 750 MAXs they had planned to be operating. About 380 were in service when a global grounding parked the fleet in mid-March, and the rest have been built but not handed over, as Boeing halted deliveries with the grounding.

Quantifying the MAX grounding’s effect on aftermarket demand is challenging, but few dispute there has been an uptick. Several carriers announced fleet changes linked to the MAX situation’s uncertainty, unveiling plans to keep operating older narrowbodies a few years longer than expected. Examples with immediate ramifications include Southwest Airlines retaining seven 737-700s slated to be parked in 2019, and American Airlines keeping 10 757s that were to have been parked by now.

Fleet-planning headaches have not been limited to the narrowbody segment. Rolls-Royce’s Trent 1000 engine struggles—a series of durability issues that have affected all variants of the Boeing 787 powerplant—have forced operators to turn to lessors or delay retirements while Rolls works to manufacture enough spare parts and line up MRO capacity to meet demand. Virgin Atlantic planned to park the rest of its Airbus A340s last year as its first A350s were delivered. But issues with its Trent-powered 787s led Virgin to keep at least one A340 in service into 2020.

Such issues rarely have a direct influence on heavy airframe maintenance—Virgin did not put any of its A340s through heavy checks to get them in shape for 2020, for instance. But the knock-on effect can lead to changes in airframe maintenance demand, such as delaying the transition of older airframes into the freighter-conversion pipeline—a process that includes a heavy maintenance visit.

Two factors that could influence near-term heavy maintenance demand are fuel costs and retirement rates. Normally, as fuel costs rise, fares increase to compensate. Demand falls, and the most expensive aircraft to operate—usually older, less efficient models—are bumped from schedules.

The good news for airlines is the price of fuel is not expected to jump soon. As of mid-December, prices had dipped 40% since midyear to around $70 per barrel for Brent crude. Production in places such as Brazil, Norway and the U.S. means the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries and its allies cannot control prices as they once did. Even a manufactured price spike by the consortium would hit a ceiling by making feasible more expensive production options such as fracking.

All of this points to a slight decline in 2020 fuel costs for airlines in the largest geographic market, analysts from Cowen and Co. project. They see U.S. airlines paying $2.07 per gallon, down a penny year-over-year, and 16 cents—or 7%—from 2018. Canadian carriers will enjoy a similar run, paying about U.S. $0.76 per liter in 2020, slightly down year-over-year.

The coming year will not be a normal one, however. The presumed return of the MAX fleet will see the industry absorbing a significant amount of capacity in a short time. The MAX’s return will be phased, with countries including China and India undertaking their own reviews and delaying approvals until well into 2020, at least. North America will be on the front end, starting with the FAA. Canada is expected to follow in short order.

Many MAXs were earmarked for growth, so the fleet’s return will not bring a one-for-one removal of older aircraft. But many MAX operators made contingency plans, keeping older aircraft flying or leasing capacity to help replace the lost seats. This has helped boost aftermarket activity.

The MAX’s return will not necessarily mean a related decline in MRO opportunities, however. Retirements may jump, which means less in-service work but a boost for used-parts feedstocks. Getting MAXs back also could help free up a few older, prime narrowbodies, likely 737-800s, for cargo conversion.

The long-term trend in airframe maintenance calls for fewer events over an aircraft’s useful life. The newest designs integrate more composites and other materials that do not corrode and offer more general durability than older models. Under Boeing’s baseline assumptions, a 787-8 will require about half as many heavy-check labor hours as a 767-300ER over comparable expected useful lives. Part of the savings will be offset by labor-cost increases, which could accelerate as the industry struggles to meet demand for technicians as it grows.

While most major advances in heavy maintenance efficiency are coming via new designs and materials, older models are helping to lower maintenance burdens as well. Programs such as Boeing’s Optimized Maintenance Program (OMP) help operators modify maintenance intervals using their own data. In many cases, the results include longer heavy-check intervals. Emirates, which operates about 10% of the world’s 777s, is using OMP to extend C check intervals on most of them to 18,000 flight hours or 1,200 days—increases of 20% compared to the 2006 program.