The Secret Pioneers Of Stealth

September 11, 2015

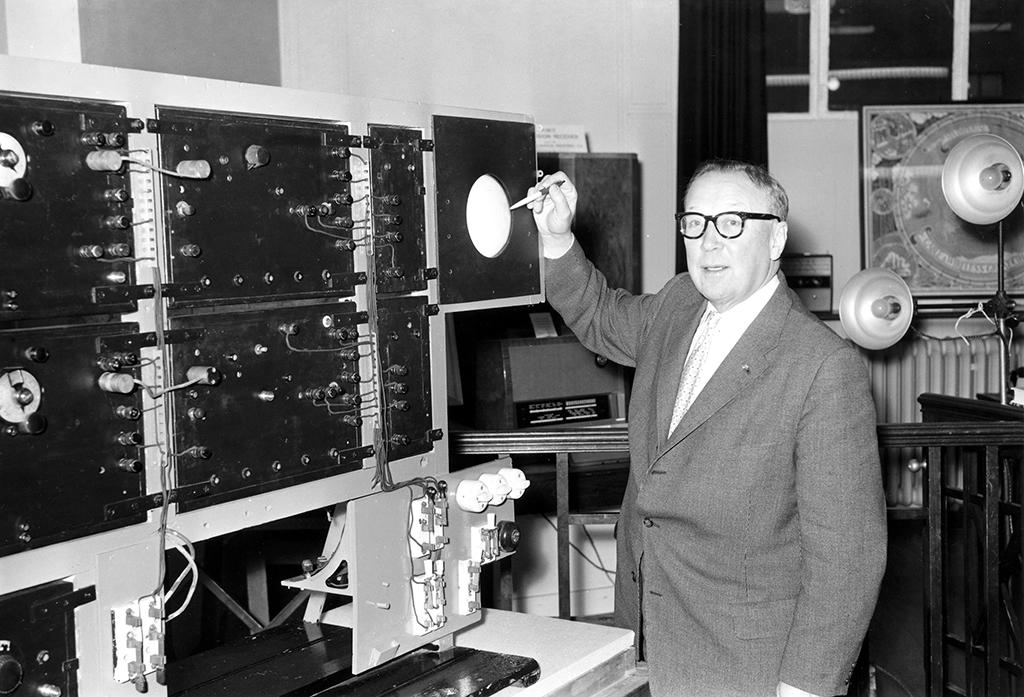

Robert Watson-Watt (1892-1973)

Before radar, all aircraft were stealthy if it was dark or they were flying above the clouds. Radar was invented independently in many places, but Robert Watson-Watt (1892-1973) was instrumental in Britain’s development of radar from a laboratory curiosity to an integral part of an air defense command-and-control system.

Clarence L. 'Kelly' Johnson

Lockheed Skunk Works founder Clarence L. “Kelly” Johnson (1910-90, on left, with pilot Francis Gary Powers) directed the first “radar camouflage” modifications to the U-2 and incorporated RAM and RAS into the A-12 Blackbird, but he was in fact highly skeptical of the value of stealth alone when not combined with speed and altitude performance.

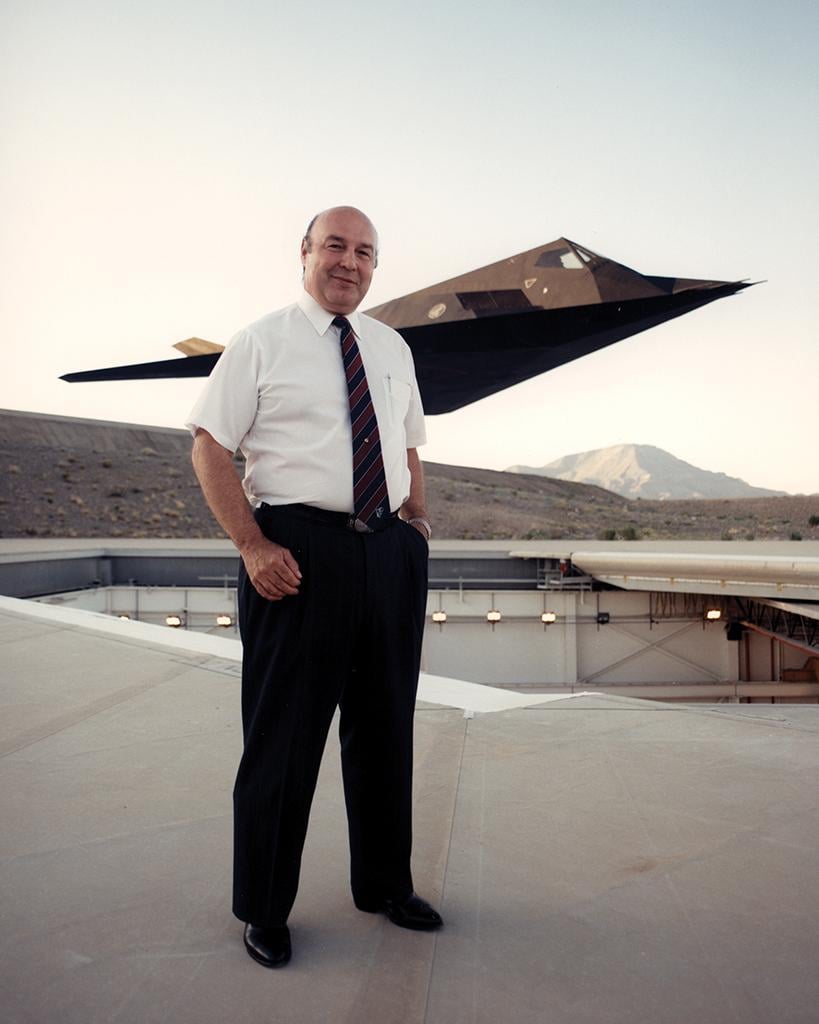

Ben Rich

Johnson’s successor, Ben Rich (1925-95), led the team that won the Have Blue development contract and made the F-117 into a workable airplane, with a combination of borrowed systems and completely innovative features. Rich said of the project’s strict secrecy: “We’re like the rabbi who hits a hole-in-one on a Saturday.”

Alan Brown

Alan Brown was part of the “Brain Drain” of British engineers who moved to the U.S. in the 1960s as the U.K. slashed defense R&D. His contributions to Have Blue and F-117 included work on the flat-panel shape’s aerodynamics and the “titanium tennis racket” screens over the infrared sensors.

Denys Overholser

Denys Overholser was recovering from a skiing accident when Ben Rich asked him to look at the RCS problem. He led the development of a computer program that would accurately model the radar return from a full-size aircraft. Difficulty: There could not be a single curve in the shape. “They decided that I wasn’t the village idiot so I became a genius instead,” said Overholser later.

The 'Whalers'

Three of Northrop’s original stealth team—known as the “Whalers” because the V-tailed, bulbous-nosed Tacit Blue prototype was nicknamed “Shamu”—visit the U.S. Air Force’s B-2 squadron in 2009. Stealth specialist John Cashen is on the left, next to Irv Waaland, chief engineer on Tacit Blue and B-2. (“You know just enough to be dangerous,” was Cashen’s summary of Waaland’s knowledge of electromagnetics.) B-2 program manager Jim Kinnu is third from the right. Also in the photo: to the right of Waaland are Air Combat Command chief scientist Janet Fender and Brig. Gen. Garrett Harencak, 509th Bomb Wing commander (now a two-star in charge of USAF nuclear weapon programs). Second from right is government B-2 engineer John Griffin, next to Northrop Grumman’s Dave Mazur.

Alan Wiechman

Stealth pioneers tend to keep a low profile, but none has done better than Alan Wiechman, who was instrumental in stealth programs at McDonnell Douglas and then Boeing for almost 30 years, but scores exactly two mentions on the latter’s website. Hired from the Lockheed Skunk Works after McDonnell Douglas’s defeat in the ATF contest, Wiechman was a founder of St. Louis’s Phantom Works and directed stealth work in two directions: reducing the RCS of conventional aircraft, and extreme-low-observable, tailless shapes. Wiechman retired in 2014 and formed a consulting company, Eagle Aerie, together with the founder of the Air Force’s Rapid Capabilities Office.

A small number of people, ranging from physicists and mathematicians to hands-on engineers, made outsize contributions to the early development of stealth, working under intense secrecy, frequently out of touch with their families and under constant surveillance.

Comments