55 Years Of Aviation Week’s Stealth Reporting

September 11, 2015

Cover Story Fail

One of the challenges of reporting on secret aircraft is that official, reliable sources may be feeding you propaganda. In its first report on the shootdown of Francis Powers’ U-2 over Sverdlovsk in May 1960, Aviation Week stated that the aircraft was “an unarmed National Aeronautics and Space Administration weather research plane whose civilian pilot had experienced trouble with his oxygen equipment at 55,000 ft. in a flight near the eastern border of Turkey” which was mostly true except that it was a CIA spyplane that had taken off from Pakistan and had not experienced any oxygen problems or flown at anything like 55,000 ft. (which was pure disinformation, intended to erode Soviet confidence in their own radar). By the following week the magazine had lost its innocence — it turned out that the Russians had identifiable wreckage (photo) and an intact Francis Powers — and published a detailed time line, including the fact that the U-2 had operated from “Watertown Strip, Nevada” — the location better known as Groom Lake or Area 51.

Lockheed Blackbird

Hiding the Lockheed U-2 — a very simple, fighter-sized airplane — had been easy. Concealing its intended replacement, the stealthy Lockheed A-12 (codename Oxcart), was a good deal harder. By July 1963, Aviation Week editor Robert Hotz was telling the Air Force that the magazine knew something about the project, and while he would show restraint to a point he had no intention of getting scooped. The result was a coordinated disclosure in February 1964 (http://aviationweek.com/blog/1963-mach-3-cruise-stealth-multirole-jet-unveiled) in which the Pentagon issued a deliberately misleading announcement that obscured the new aircraft's mission, misstated its designation and identified its secondary customer as the primary one. The Russians had known enough about the project since 1960 to start development of its intended nemesis, the MiG-25.

We Shot an Arrow

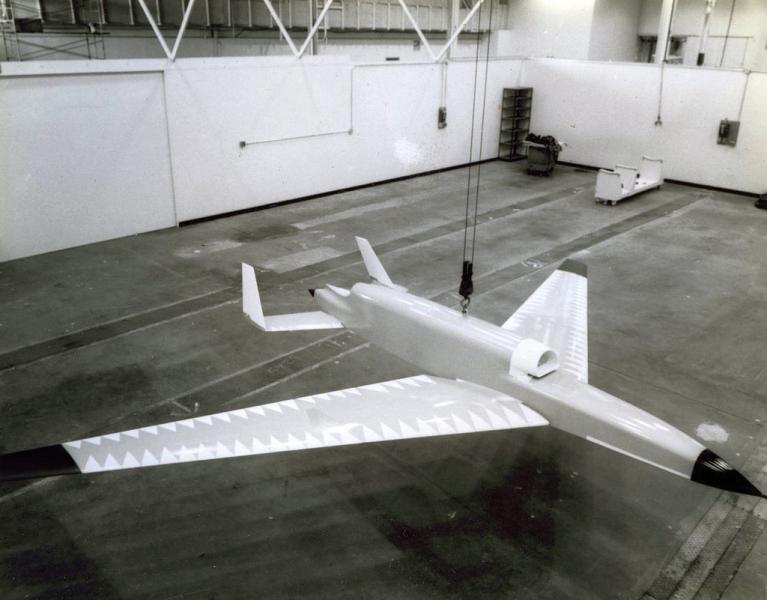

The first aircraft designed to survive primarily by stealth was the Teledyne Ryan AQM-91 Compass Arrow unmanned air vehicle, a very ambitious and costly project that was mainly designed to probe China’s nuclear secrets. To this day, it is one of the highest-flying subsonic airplanes ever built and its unique optical bar camera is still in use on the U-2 (http://aviationweek.com/blog/stealth-80000ft-375-million-copy-did-we-say-was-1970). Barry Miller, an Aviation Week technology writer, heard rumors in early 1967 of a USAF program called “Dark Eagle.” He did not publish them in the magazine, but in a confidential Boston-based brokerage newsletter. The USAF’s White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, unintentionally released the “Firefly” name in announcing tests of a “special purpose vehicle” in a January 1968 press release, and Aerospace Daily followed up with a report in November, a few months after its first flight.

Stealth Snippets

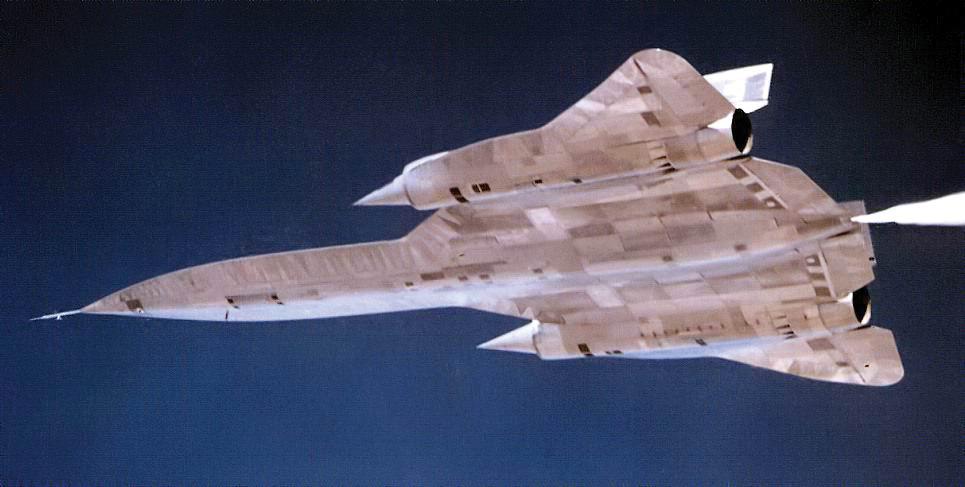

Radar-cross-section model tests of Lockheed and Northrop stealth designs in 1975 had shown results that most of the world considered flat-out unattainable. To preserve technological surprise, security was unprecedented. Before the vault doors shut, however, Barry Miller reported in January 1976 that the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency was working on stealth demonstrators with Lockheed and Northrop. In August, the magazine correctly reported that Lockheed had won the contract, and in June 1977 said that it would fly by the end of the year, powered by two J85 engines. It was another decade, though, before anyone hinted at how strange it looked. By October 1981, the magazine was reporting that Lockheed’s operational aircraft was “F-18-size” with a planform similar to that of the space shuttle, and that another “fighter-size” Northrop demonstrator (Tacit Blue) was ready to fly.

Flying Wings or No Wings

Aviation Week’s Jan. 29, 1979, issue included detailed stories about the development of a new bomber, illustrated with concept art from Boeing, Rockwell and other companies — but not from Northrop, where the idea of a bomber was seen as a remote possibility. Some of the concepts illustrated pointed to the possibility of stealth technology for a new bomber. Others were as far from what the Air Force was really looking at as it was possible to get, including this Rockwell design with wings that folded parallel with the fuselage in low-level flight.

Overhead Assets

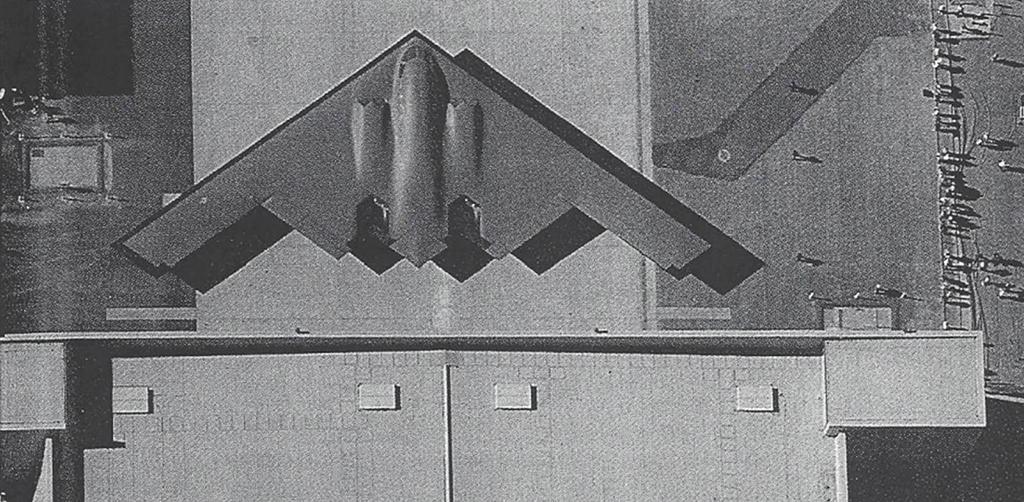

Aviation Week’s West Coast technology editor Michael A. Dornheim was the last person anyone would expect to skip the rollout of the Northrop B-2 in November 1988, so his absence was noted. But he was present, in a sense: having noted that nobody had closed the airspace over Palmdale, California, Dornheim rented a Cessna 172 and overflew the event (http://aviationweek.com/blog/1988-b-2-stealth-unveiled), getting the plan-view image that the Air Force wanted to conceal. While some unfortunate security person no doubt ended up in what the Royal Air Force would call a “stand-up, no-tea-and-biscuits meeting” with the boss, it’s most unlikely that the Russians learned anything from Aviation Week’s scoop, since the rollout arrangements had been announced in plenty of time to set up a pass with a Cosmos reconnaissance satellite.

That Doesn’t Look Like a Black Hawk

After one of the Sikorsky Black Hawk helicopters used in the May 2011 operation to assassinate Osama bin Laden in Pakistan crashed in the compound, the U.S. special operations team took steps to destroy it — but could not safely reach the tail section, which had been broken off by the compound’s concrete wall and lay outside it (http://aviationweek.com/defense/bin-laden-raid-leaves-stealth-helicopter-clues). Aviation Week was the first major publication to note that it was very different from a stock Black Hawk tail — and that the airport in Elmira, New York, which had nothing special about it other than being the home of Sikorsky’s rapid-prototyping division, had been fogged-out on Google Earth.

High-Flying Stealth

Aviation Week editors Amy Butler and Bill Sweetman combined reporting with analysis of technical possibilities, funding streams, strategic needs and even airplane shelters to tell the story of Northrop Grumman’s high-altitude, long-endurance stealth unmanned air vehicle, believed to be designated RQ-180 (http://aviationweek.com/defense/secret-new-uas-shows-stealth-efficiency-advances). Sponsored by the U.S. Air Force and, probably, the intelligence community, and most likely managed by the Air Force’s Rapid Capabilities Office, the RQ-180’s roles may include reconnaissance support for the Long-Range Strike Bomber, and it has almost certainly provided technology for Northrop Grumman’s bomber design.

“News is what someone wants to suppress. Everything else is advertising,” is a statement reliably attributed to dozens of people (unusually, not including Winston Churchill, Mark Twain or Will Rogers), but it is nonetheless true. Reporting on defense naturally runs up against the limits of classification, because one of the reasons for making information secret is to prevent its public dissemination. Aviation Week earned its “Aviation Leak” nickname decades ago. Very often, reporting is the best test for whether something is properly classified; if word has reached the ears of editors, it has almost certainly reached foreign intelligence services first.

As Aviation Week & Space Technology approaches its centennial in 2016, our senior editors cast their eyes back to iconic developments that have changed the shape of the industry – and to the future to predict the paths they might follow. In the first of a special series, we explore the art of deception: stealth.

The Development Of Stealth And Counterstealth

Stealth Technology: How Not To Be Seen