The locations circled in red are seal damage to the windshield caused by lightning strikes on a United Air Lines Boeing 787.

The weather that existed for departure from London’s Heathrow Airport (LHR) on Oct. 10, 2014, was moderate rain from a layer of stratus clouds with tops at 10,000 ft. The weather could hardly be considered threatening for experienced pilots flying a modern transport category aircraft designed and certified to the extensive standards of Federal Aviation Regulation Part 25.

The United Airlines Boeing 787 was only six minutes into its flight from LHR to Houston’s George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) when the aircraft was struck by lightning from a seemingly innocuous stratus cloud layer, causing a cacophony of failures resulting in the aircraft making an emergency return to LHR with key components disabled. The lightning strike caused three of the five primary display units to blank. The captain’s forward windshield heat was inoperative.

Let’s step back from the NTSB’s official report and think of this from the pilots’ perspective. They were flying a heavily loaded 787 on a trans-Atlantic flight in which three of the five primary flight displays were blank. There wasn’t a checklist that fit this malfunction. Picture yourself in a simulator training session facing the loss of critical components such as the display of flight information while you scramble through the pages of the Quick Reference Handbook trying to find a checklist that would apply.

That is a considerable distraction and adds workload for a flight crew. The United crew had an additional malfunction to consider, that of the inoperative windshield heat. That checklist was easy to find, but the procedures failed to restore heat to the windshield due to the damage from the lightning strike.

The windshield malfunction carries significant operational restrictions. The workload had to be considerable dealing with the consequences of these multiple failures. They prudently decided to return to LHR, but this too added workload coordinating with air traffic control for a return to LHR while also getting the aircraft down to its landing weight. The crew’s professional performance brought the aircraft back to LHR without further incident.

Post-incident inspection revealed lightning strike attachment points where the lightening made contact on the left side of the nose and around the captain’s windshield. Other lightning attachment points were noted on the left outboard aileron. The NTSB’s final report determined that the displays were rendered inoperative by the lightning strike, and further noted the lack of guidance to the flight crew to perform a power reset to the display.

Where Does Lightning Occur?

The French Aerospace Lab estimates on average that each aircraft in the U.S. commercial fleet is struck by lightning every 1,000 flight hours. The U.S. Air Force notes that more than 50% of military aircraft weather-related in-flight mishaps are caused by lightning.

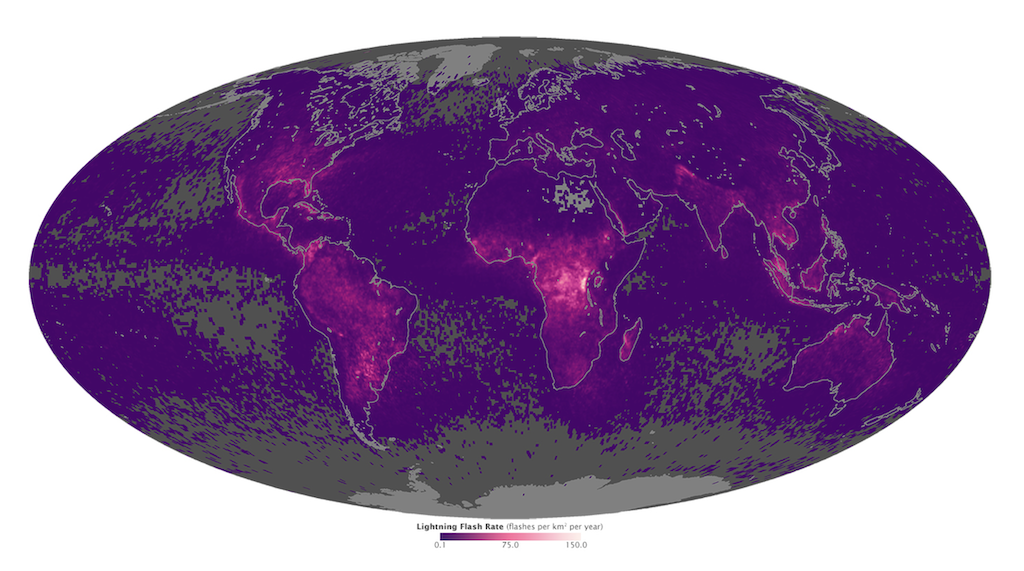

According to NASA’s Earth Observatory, lightning occurs more often over land than the oceans, and more frequently closer to the equator. Stronger convective activity is to be expected over land rather than water bodies because the earth absorbs sunlight and heats up faster than water, causing strong convection leading to the formation of lightning producing storms.

In the image above, the regions with the highest number of lightning flashes are shown in pink. The data was collected from 1995-2013 by NASA satellites. Central Africa and South America have regions exceeding 20 strikes per square km per year. The area of lighter color in Central Africa experiences more than 70 strikes per square km per year. The highest amounts of lightning occur in the far eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (158 strikes/sq km/year). The highest rate of lightning in North and South America occurs in northwestern Venezuela.

Further analysis of the data revealed interesting regional trends. NASA’s Daniel Cecil, a member of the Global Hydrology and Climate Center’s lightning team, noted the increased concentration of lightning over far eastern India in May, a time of year when the weather becomes unstable and changeable, just before the onset of the monsoon.

Non-Threatening Weather

The National Severe Storms Laboratory recommends avoiding those atmospheric conditions where the risk of strikes is greatest to decrease the chance of a direct lightning strike. That sounds like common sense, but it isn’t as easy as it sounds, especially when considering that atmospheric scientists have described lightning as a capricious, random, stochastic and unpredictable event.

There is a commonly held perception that most lightning strikes occur close to weather cells which exhibit significant convective activity, but the historical records of aircraft lightning strikes indicate otherwise.

Let’s review a sample of past incidents to determine which weather conditions produced the most number of lightning strikes and what difficulties the flight crews encountered while trying to avoid the associated weather. The analysis included 328 events in the NASA Aviation Safety Reporting System, 49 incidents in the FAA incident database and 195 incidents from the UK Civil Aviation Authority Mandatory Occurrence Reporting System.

Surprisingly, 63% of the lightning strikes occurred in weather that flight crews did not associate with the threat of adverse weather. A substantial portion of aircraft lightning strikes occur to aircraft in a cloud where there is no evidence of precipitation nearby, or even to aircraft flying in clear air at an assumed safe distance from a thundercloud. Strikes to aircraft flying 25 miles from the nearest radar return of precipitation have been reported.

In contrast, only a small percentage of strikes (12%) occurred when flight crews were attempting to detour around observed weather cells (observed either with the weather radar or visually.) Light precipitation, which would hardly be considered threatening weather for a transport aircraft, was present in 6% of the lightning strikes. Moderate rain was present in 6%. Snow was present in 4% (and yes, lightning and threatening convective activity does occur in snow storms).

How do these numbers compare with past studies done by the airlines and manufacturers? A study of 99 lightning strike incidents that occurred to United aircraft found that roughly 40% of all lightning strike incidents occurred in areas where no thunderstorms were reported. Only 33% of the strikes occurred in the general area of a thunderstorm.

It is interesting to compare and contrast the data sample above with a study done in 1971. Five U.S. commercial airlines (American, Braniff, Continental, Eastern and United) and the General Electric High Voltage Laboratory formed the Airlines Lighting Strike Reporting Project. The project had the objective of obtaining a greater understanding of the conditions under which aircraft are struck by lightning and the resultant effects on aircraft structural, electrical and avionics systems.

The report covered 153 lightning strike incidents that occurred to turbojet transport aircraft. It found the following conditions existed at the time of lightning strikes to aircraft:

- 85% were within a cloud

- 83% were experiencing precipitation

- 72% were experiencing turbulence

- 50% experienced electrical activity (earphone static, St. Elmo’s Fire) before the strike

- 95% of the strike incidents occurred below 23,000 ft.

- 5% occurred between 33,000 and 37,000 ft.

A joint project by the National Severe Storms Laboratory, NASA Langley Research Center and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center using a Convair F-106B found that the majority of direct strikes to the research aircraft occurred during the decaying stage of cell evolution. Environmental conditions such as turbulence and rain intensity during the direct strikes at low-altitude flights were characterized by negligible to light levels of both. The probability of a direct strike to the airplane in a thunderstorm increases with the decreasing rate of lightning flashes.

We discuss the role of airborne weather radar in Part 2 of this article.