On March 21, 2018 a Gulfstream GV descending to land at Miami International Airport (MIA) encountered turbulence and three of the five passengers were injured, one seriously. There were two professional pilots and a flight attendant on board as well as the passengers. No one wearing a seatbelt was injured.

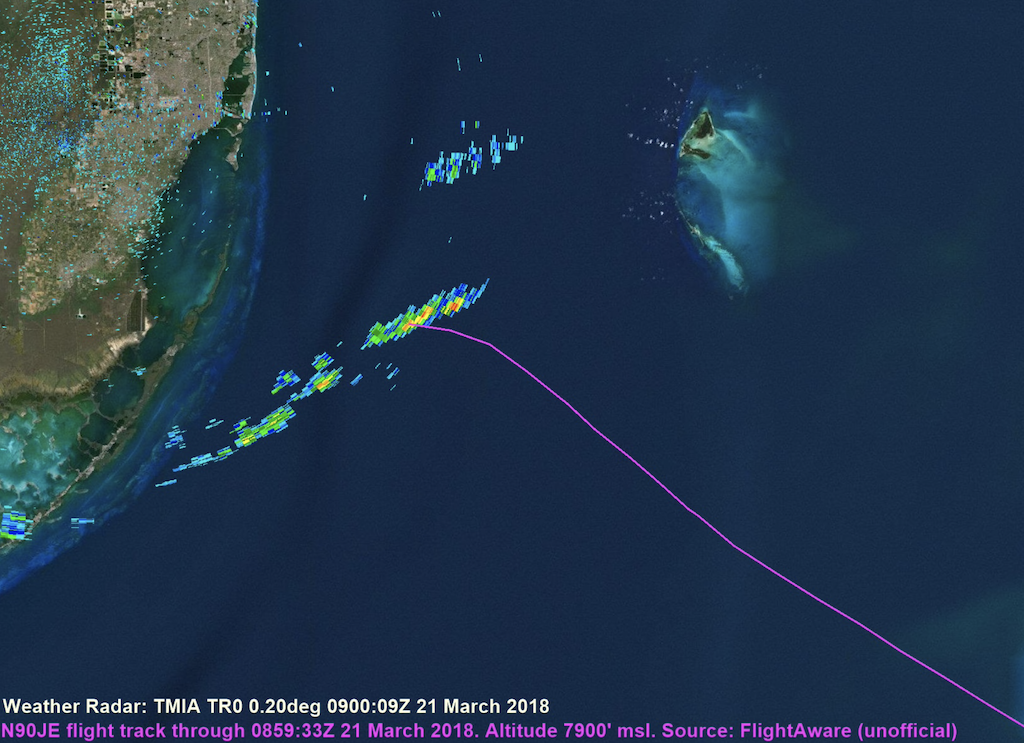

The pilot in command (PIC) used the seatbelt sign to communicate with the cabin occupants. He turned it on during the descent from 27,000 ft. His radar began painting red cells about 25 mi. ahead as they passed 12,000 ft., and he cycled the seatbelt switch at 9,000 ft. when the flight began to encounter light chop.

The aircraft flew through heavy rain at 7,000 ft. and experienced a drop the copilot estimated to have been 500-to-1,000 ft. Shortly thereafter, the flight attendant notified the pilots of the three injured passengers. In a futile gesture, the pilot cycled the seatbelt switch one more time before landing.

The accident report did not mention whether or not the crew had ever briefed the flight attendant about possible turbulence or if they ever made any announcements to that effect to the passengers. The accident took place at 0524 local time after a long flight, and the PIC may have felt it wasn’t necessary to wake or disturb the passengers.

The people in the cabin were not aware of the threat. The chime of the seatbelt sign did not signify danger to them. They had a different mental picture of what was going on than the pilots. They didn’t know when to sit down and buckle up.

Time and again the accident record shows that cabin crews aren’t on the same page as pilots. I investigated two turbulence cases in 2011-12, one involving an Airbus A320 and another involving a Boeing 737-700 that illustrate this. One of the airliners flew over a rising cumulus column during an afternoon arrival into Ft Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (FLL); the other flew over a rising column climbing out of Houston’s George Bush Intercontinental Airport (IAH) on a stormy late afternoon.

The A320 was descending through 12,400 ft about 45 mi. west of FLL when the crew flew through a developing cumulus cloud and experienced a 2 G jolt that seriously injured the forward cabin flight attendant and caused minor injuries to two others. Prior to descent, the captain had briefed the cabin crew to begin cabin clean-up early and then be seated. He turned on the seat belt sign. The flight attendants were still in the process of preparing the cabin for landing when the accident happened.

In the Houston case, the captain cycled the seatbelt sign climbing though 15,000 ft., signaling the end of sterile cockpit rules. He had the radar tilt set to +1 degree. The ride was smooth, and when there was a sudden violent drop passing 22,000 ft., it caught him by surprise. Two flight attendants were seriously injured. The captain thought the cabin was secure, but one of the injured flight attendants said it was normal protocol to get up after the sterile cockpit signal and pilots should “just let us know” about the turbulence.

The pilots in these cases all thought they provided their cabin crews and passengers adequate warning, but they didn’t. Flipping on the seatbelt sign—even cycling it a couple of times—isn’t an effective message. You have to do more. Start with a preflight briefing and use a graphical printout of the route of flight with areas of potential turbulence circled. Ask your cabin crew if your PA announcements can be heard over the engine noise. Be explicit when you want everyone strapped in. When those red cells start showing up on the radar, let people know. Remind people to use the lav while conditions are smooth and before you descend.

As pilots, we have to accept the burden of communication. When we tell flight attendants to stop service, we go against their service mindset. When we brief passengers, we have to be informative without scaring anyone. We have to be persuasive but talking to people isn’t usually our strong point. So, we must practice!

The NTSB’s 2021 turbulence study made many suggestions for ways to reduce turbulence injuries, but they didn’t spend much time on crew communications. I think it’s the key to keeping people safe when turbulence looms.

Turbulence: Not Just An Airline Problem, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/turbul…

The Crosscheck column by Roger Cox explores the interaction between regulators/investigators and pilots/operators. Send comments to [email protected].

Comments