Photo of the initial impact point and ground scar.

A Daher TBM 700 single-engine turboprop crashed during an attempted go-around from an approach to Capital Region International Airport (LAN) in Lansing, Michigan, on Oct. 3, 2019.

Engineering staff of Daher, the current manufacturer of Socata airplanes, calculated the stall speed of the accident airplane at its actual weight and CG with takeoff flaps to be 74.2 kt. The stall speed could have been as low as 68 kt. if the flaps were halfway between the takeoff and landing position, as found in the wreckage. That number, however, does not take into account bank.

A supplement to the TBM 700 flight manual shows the increase in stall speed with bank. If takeoff flaps are set, stall speed increases 6 kt. between 0 and 30 deg. of bank, 15 kt. at 45 deg. of bank, and 32 kt. at 60 deg. of bank. The airplane was also in a slight climb, which would have marginally increased the load and the stall speed.

Since the airplane’s last recorded airspeed was 74 kt., the airplane would have stalled at that speed with only 30 deg. of bank with the flaps between landing and takeoff. The bank was probably greater than that.

It appears from the evidence that the pilot decided to go around, pushed the throttle forward, and the airplane banked and stalled. The right main gear and the flaps were still in transit when the airplane struck the ground. The pilot pulled the power off and leveled the wings just before impact, perhaps to reduce the energy of the crash.

The 48-year-old pilot had completed the SIMCOM TBM 700 initial qualification a year before the accident but had only obtained his commercial pilot certificate in May of 2019, five months before the accident. Of his 1,404 total flight hours, only 76 were in the TBM 700 and they were all flown in the past year. He had also logged 9.8 hours in a TBM 850. Three weeks before the accident, he passed an instrument proficiency check in a Redbird SR22 simulator.

An SR22 simulator would not provide the engine torque effect of the TBM at full power. Investigators did not interview the SIMCOM staff who trained the pilot and did not determine if he had ever experienced a high thrust, low speed scenario in his training.

A non-current pilot-rated passenger was on board the flight. He was a friend of the accident pilot, and his wife said he had no role in the operation of the flight. As an instrument-rated flight instructor, he might have come along to coach or assist the relatively inexperienced pilot in an informal way

Another experienced TBM pilot who had flown N700AQ was interviewed by investigators. He said he had been authorized to be a mentor pilot for the accident pilot by an insurance company. He was supposed to have flown 25 hours with that pilot to meet insurance requirements but had only flown one trip with him in 2018.

The TBM pilot said he had intended to go along on the accident flight, but he was unable to go because of a scheduling conflict. It was this pilot who introduced the passengers to the accident pilot and helped to arrange the flight.

As a result of this interview, the NTSB discovered that the Part 91 flight was actually being operated as a charter. An exchange of emails and text messages between the principal passenger and the pilots established that charges would be made for the use of the airplane and the pilot’s services. It was also established that the accident pilot had operated a previous charter flight in 2018 for the same passengers. At that time, he had no commercial certificate, and at no time did he have a Part 135 certificate.

French Safety Bureau Study

The TBM 700 is built in France and was certified by European authorities in 1990. The French accident investigation agency, Bureau d’Enquêtes et d’Analyses pour la sécurité de l’aviation civile (BEA), recorded 36 TBM 700 accidents between 1990 and 2010, 19 of which involved loss of control in flight (LOC-I). The BEA undertook a study of these accidents, with emphasis on loss of control while banking to the left during approach. That study was published in 2014 and was referenced by the NTSB in the Lansing accident.

The BEA found six examples of the left banking LOC-I type accident. Generally, the speed was lower than what was specified in the flight manual for the airplane’s configuration, and power was advanced rapidly from idle to full throttle. In addition, these accidents occurred while the pilot was flying manually.

The BEA study also cited a British TBM demonstration flight in 2003 in which the pilots deliberately flew the airplane at slow speeds and high power. They found the airplane had a tendency to roll left during the stall, but the roll was controllable at speeds above 70 kt. The slower the speed, the more pronounced was the roll. They found the airplane was controllable within its certified envelope.

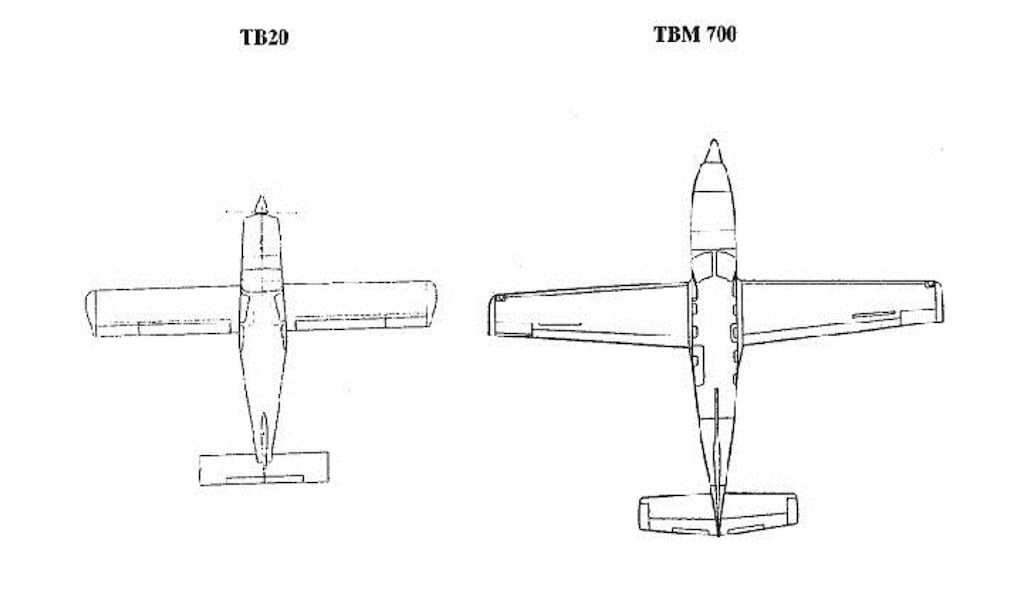

Operational factors better explained the accidents. First, the TBM 700 was designed for non-professional pilots needing to travel frequently over long distances. Second, most TBM pilots transitioned to the airplane from lighter aircraft like the Socata TB20 or the Cessna 310. Third, there was no record of such accidents by professional pilots at air transport companies or in the military.

The TBM 700 has spoilers to assist the ailerons in roll but has a greater wingspan than the typical small trainer. As a result, the TBM’s roll rate is less than that of the TB20.

The maximum value of the TBM’s engine torque at full power applied at left mid-wing is about 2.66 times as great as that of the TB20. In a piston engine, power responds to throttle inputs immediately, while in the turboprop, regulator mechanisms can cause a delay in engine response.

In Part 3 of this article, we describe more findings from the BEA study and offer our conclusions and comments.

A TBM 700 Experiences A ‘Torque-Induced Stall,’ Part 1, https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/tbm-70…

Comments

A reminder to readers that the provided stall speed relationship with bank angle is only for level, coordinated turns. For a given aircraft and flap setting, there’s one ‘critical’ AOA where stall begins. That AOA may be reached in zero bank angle pullups or, conversely, not reached in banked but lightly-loaded maneuvers.