In Part 1, we discussed how a Beech King Air 200 wound up in the frigid waters of Unalaska Bay, Alaska.

It seems likely that the pilot knew the King Air was overweight.

When investigators re-created the weight and balance form for the flight, they found the 12,500-lb. maximum weight airplane actually weighed 13,269.6 lb. and its estimated center of gravity was about 8.24 in. aft of the approved aft limit. The three crewmembers weighed far more than the standard 189 lb. each, and the raft, survival gear, ladder and crew baggage all added to the overweight situation.

In addition, investigators obtained a fuel slip signed by the fueler that showed that the airplane was fueled to its maximum limit, 544 gal. This exceeded the pilot’s estimate of 450 gal. by almost 630 lb. Even if the fuel had been 450 gal., the airplane still would have been overweight. Reconstruction of the airplane’s previous flight showed that flight was overloaded by over 1,000 lb.

Investigators delved into exactly how weight and balance was supposed to be done. There were two methods, one using the manufacturer’s calculated method, done in “longhand” using a calculator. The other method was a graph index method using an American Aeronautics plotter. According to the program manager, pilots often used the ForeFlight program to do the longhand method.

There were no company controls on the basic operating weight or standard equipment in ForeFlight. That program was simply a convenient calculator, and the entries were the pilot’s responsibility. The pilot was supposed to enter the weight and balance information on the first page of the flight log. That log sheet from the accident flight was missing.

All flight log sheets were stored at company facilities in Anchorage. However, Aero Air did not audit or systematically review those log sheets for discrepancies.

The company set no limits on tailwind takeoffs in the King Air, although they did set a 10-kt. maximum tailwind limit on transport category airplanes like the Learjet. Pilots were supposed to complete a flight risk assessment that would account for that risk.

A full flight-risk assessment should have been done by the pilot because of the conditions that existed at the time of the accident airplane’s takeoff, but he did not do one. Company officials would not know if these assessments were being done because they did not audit them either.

Steep Terrain

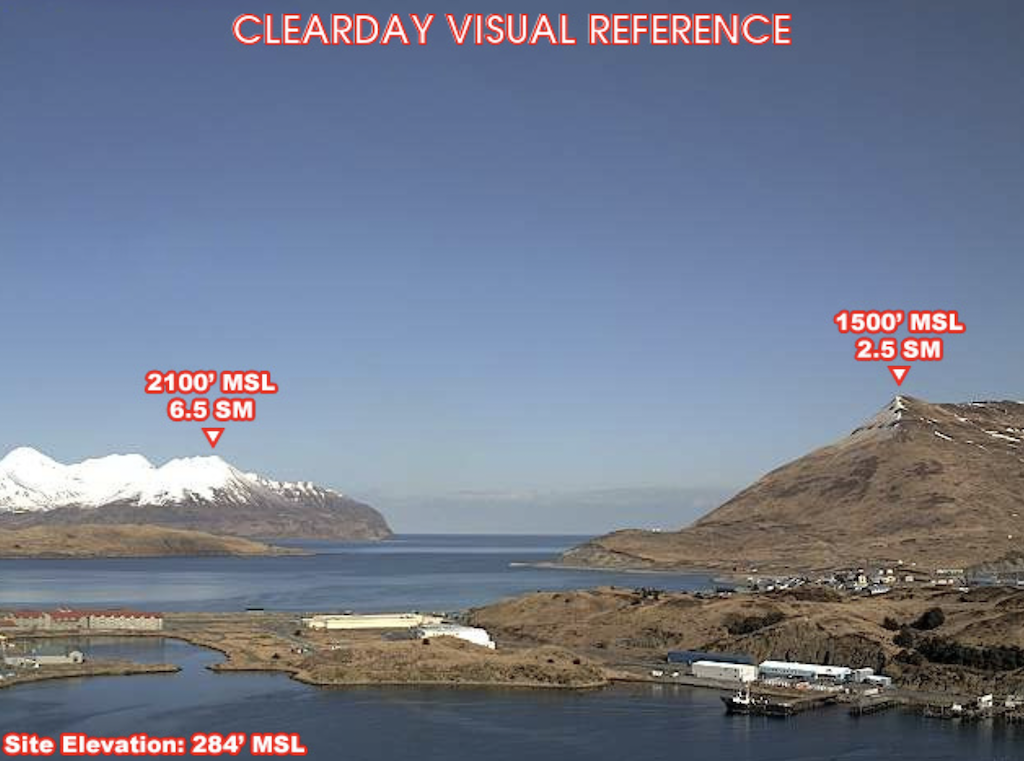

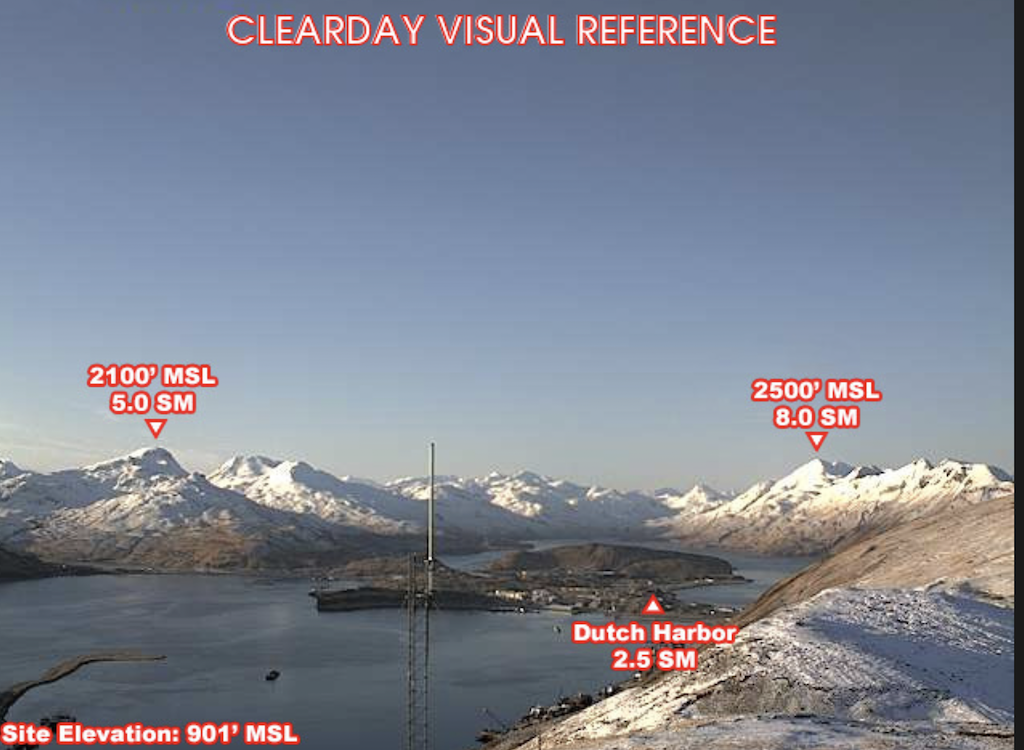

Unalaska is a fishing port about halfway out the Aleutian Island chain from mainland Alaska. The northeast area of the settlement contains the port facilities and is called Dutch Harbor. Unalaska Airport nestles on the extreme southwest fringe of a very steep mountain island, Amaknak Island, which rises to 1,700 ft. ASL. The southeast end of the 4,500-ft.-long runway rests on a narrow strip of land that connects Amaknak with the much larger Unalaska Island.

When an aircraft departs to the northwest off Runway 31, it flies over the open water of Unalaska Bay. A right turn is needed, but there is maneuvering room to climb. When it departs to the southeast off Runway 13, there are multiple hazards and obstacles, including the village of Unalaska on the right and Mount Newhall, 2,039 ft. ASL, straight ahead. The chart supplement for Unalaska says that a vessel fueling dock is 1,300 ft. off the end of Runway 13 and there is vessel traffic within 1,500 ft.

The FAA takeoff minimums and obstacle departure procedures for Unalaska Airport are revealing. Takeoff minimums for Runway 31, the one used by the pilot, were 600-2 (600-ft. ceiling and 2-mi. visibility). Takeoff minimums for Runway 13 were 1,000-3, and NA (not authorized) At Night-obstacles. In other words, the accident flight would not have complied with takeoff minimums if it took off before 1015 AKST.

An NTSB review of weather observations near the time of takeoff showed that wind gusts were even stronger than broadcast at 0756. The 1-min. observations from the AWOS showed that at 0806, the wind was from 120 deg. at 21 kt., gusting to 33 kt. Very few airplanes can depart a 4,500-ft. runway with a 27-kt. tailwind component.

NTSB Conclusion

The NTSB concluded that the probable cause of the accident was “The pilot’s improper decision to take off downwind and to load the airplane beyond its allowable gross weight and center of gravity limits, which resulted in an aerodynamic stall and loss of control. Contributing to the accident was the inadequacy of the operator’s safety management system to actively monitor, identify and mitigate hazards and deficiencies.”

It seems likely that the pilot knew the King Air was overweight. A cursory review of all the weights could have shown that, and he had fuel gauges to check fuel weight. He also knew the tailwinds were gusting to at least 22 kt., unless he somehow didn’t hear the AWOS that he received in the cockpit. He decided to try the takeoff anyway. Experience in flight hours doesn’t necessarily translate to an attitude of compliance with procedure or good judgment.

Having an SMS also does not guarantee that an operator will catch all the potential safety risks, even the glaring ones. Aero Air had a relatively good safety record, with only one previous accident in the NTSB database. When they hired a new pilot, what attitudes and habits did he bring with him, and what challenges did the new Alaska operating environment create for him?

Would the pilot have been criticized if he had reduced the fuel load to make the takeoff weight and balance within limits? Would he have been criticized if he had delayed the flight until takeoff minimums could be met? What did Aero Air’s culture and training tell him was the right thing to do?

Aero Air’s director of operations said in a submission to the safety board that the company was taking the accident very seriously and would have a robust response. The NTSB has given him some areas to focus on.

Tailwind Takeoff, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/tailwi…