On-aircraft experience in addition to simulator time is key to training pilots in aircraft upset recovery, safety and training experts say.

“Simulators are different than airplanes. The way your brain processes things and thereby the way you react to a situation is going to be different,” said Scott Glaser, speaking Dec. 2 during the NBAA VBACE virtual conference.

“The research shows that you need to train in an environment like the environment you’re going to experience these events in, so that means at least part of the training must be in an aircraft,” he advised.

Glaser is senior vice president of training provider Flight Research, of Mojave, California, and a member of the NBAA Safety Committee. Joining him in a discussion on Upset Prevention and Recovery Training (UPRT) were committee members Janeen Kochan, president of Aviation Research, Training and Services of Winter Haven, Florida, and Paul Ransbury, CEO of Aviation Performance Solutions of Mesa, Arizona.

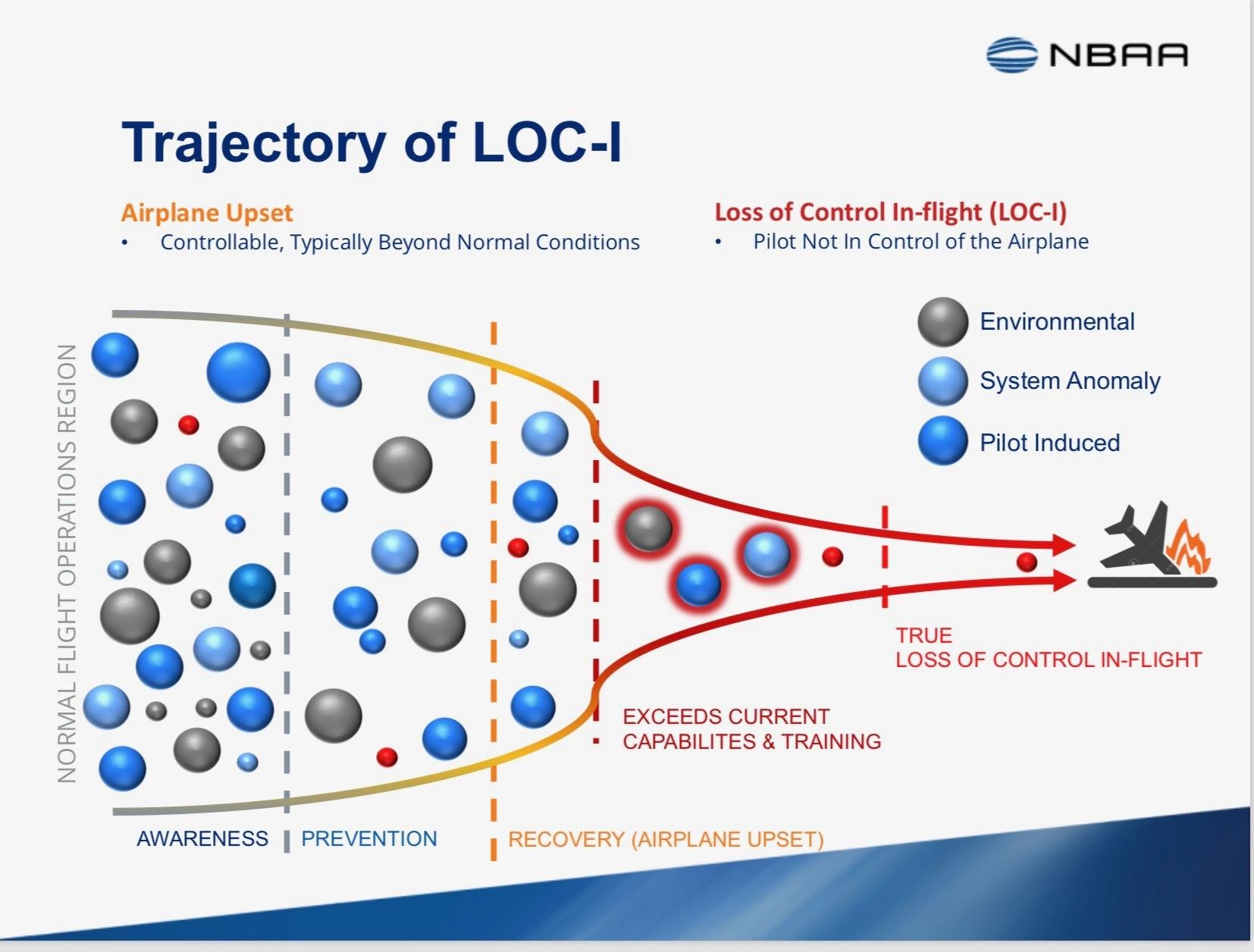

UPRT is designed to prevent Loss of Control In-Flight (LOC-1) accidents or incidents that can result when an aircraft deviates from its intended flightpath and the pilot loses control. LOC-1 “is generally a consequence of an airplane upset,” the FAA advises.

Among the VBACE panelists, there was consensus that on-aircraft training is a needed element in helping pilots react to upset conditions—unexpected situations in which an aircraft diverges from its intended state by exceeding pitch, bank angle or airspeed parameters, but the pilot still has control.

“We’ve found that even initial exposure to on-aircraft training is valuable when [pilots] go into the simulator because they can at least relate to those physiological and psychological cues that do not exist in the simulator,” Kochan said.

“We can talk all day long about having a surprise event in simulator training and the scenario might be construed very well. But there is not a pilot in a simulator who doesn’t know they are on the ground and that no matter what, they are going to walk away from this,” Kochan added.

The FAA in March 2016 issued new standards for extended envelope and adverse weather training of airline pilots on full-flight simulators under its Part 60 Change 2 regulation. As of March 2019, simulators were required to support five additional training tasks: recognition of and recovery from a full stall; upset prevention and recovery; engine and airframe icing; takeoff and landing with gusting crosswinds; and recovery from a bounced landing.

“For most of the normal flight envelope, simulators do a great job. But like all things, there are some places where they are limited,” Glaser said. “In recent years, there has been a good push to add upset training in general to every pilot’s training curriculum, but that’s mostly been simulator-based, at least from a regulatory standpoint.”

Ransbury said: “Everybody on this call would agree that the best mitigation of loss of control in flight is through upset training and it is also through the use of on-aircraft training. The problem with airline pilots before regulations changed is that [it is] cost- and time-prohibitive so they do the best they can with simulator training.

“One of the things that we learned by training the instructors is unless the instructors have real-world upset training experience, they do not give sufficient emphasis to the human factor [aspect] as part of the upset training while they are in the simulator,” he added.

The best solution to prevent LOC-1 is a combination of academics, on-aircraft training and simulator time, Ransbury said.

Comments