There were a few times in my Air Force career when I felt like I was the subject of a science experiment. The worst of these was when we pilots, navigators and other crew members were required to sit in a tent and then were exposed to a chemical gas.

“They” said it was to train us to remain calm under attack, but I suspect the laboratory scientists were collecting data on how far they could push us, their compliant subjects. I started calling myself an Air Force lab rat. Laboratory rats, otherwise known as rattus norvegicus domestica, are bred and kept specifically for scientific research. Rats are cheap and the knowledge gained justified the inevitable losses. Ever since my lab rat days, I’ve been on the lookout for these science experiments that didn’t have my best interests at heart.

You might argue that being a lab rat is part of the price we in uniform had to pay, and I think there is truth in that. I’ve never signed up for lab rat status as a civilian pilot, and yet I get that feeling now and then. Over the years I’ve come up with a few defense mechanisms and witnessed a few others from my fellow test subjects. I don’t think there is any ill intent from those conducting the tests, it is more about them trying to do their jobs without thinking about the impact on us doing ours. A few examples are in order.

The ATC Lab Rat

A friend of mine at American Airlines was on very short final to Chicago Midway’s Runway 31C at about 400 ft. with clearance to land. There was a long line of aircraft on the ground waiting to take off on that, the longest runway in use. Tower instructed my friend to sidestep to Runway 31R, well inside their stable approach criteria. “We can’t do that,” they responded. “Go around.” So, they went around.

I wonder how many times that tower controller instructed aircraft to do the low altitude sidestep and how many times the aircraft complied. One can imagine the scientist behind the microphone keeping a mental tally of the number of lab rats he or she was able to manipulate into the unsafe sidestep. Our American Airlines pilot performed perfectly, keeping his aircraft and passengers safe while refusing to become the next rattus norvegicus domestica.

The Chief Pilot’s Lab Rat

Before I showed up at my first civilian flight department, they routinely flew from Houston to London with a basic flight crew of two pilots and a flight attendant. The trip in our Challenger 604s required two legs and about 13 hours of crew duty time if everything went to plan.

Then one day the company’s chief executive officer decided to go to Munich instead, causing the duty day to lengthen to 14 hours, right at our limit. That became the new routine. I flew this trip for my introductory flight with the flight department and was exhausted by the end of the day. I was 43 years old at the time and thought the ravages of old age had finally hit me. But that was nothing compared to the return, which clocked in at nearly 17 hours of duty time.

I told the chief pilot, my new boss, that I was unable to fly 17-hour days and would refuse that trip in the future. He told me that mine was the first complaint and that I would either have to adapt or find another job. I told him I would start the job hunt immediately. My name was taken off the schedule and the other pilots started asking questions. Seven of the eight remaining pilots marched into the chief pilot’s office and said that they too would never again fly a 17-hour day with a basic crew. (The lab rats had mutinied.)

The chief pilot had no choice but to start scheduling a crew swap in Boston to make the trip work. He made sure I was on the first trip where this happened so I could explain the reason for the crew swap to the CEO. I did just that and the CEO responded with a smile, “That’s good. I want you guys to be safe.”

The Aircraft Manufacturer’s Lab Rat

One of the trite sayings that is universally accepted by the unsuspecting and understood to be false by those who know about these things is “safety first.” If safety was truly first in our profession, we would never take to the skies. That you cannot build an aircraft with zero risk makes complete sense, but would you knowingly fly an airplane where safety was compromised to increase the manufacturer’s profit? Take, for example, the need to keep the aircraft from stalling by providing the pilot a better idea about the wing’s Angle of Attack (AOA).

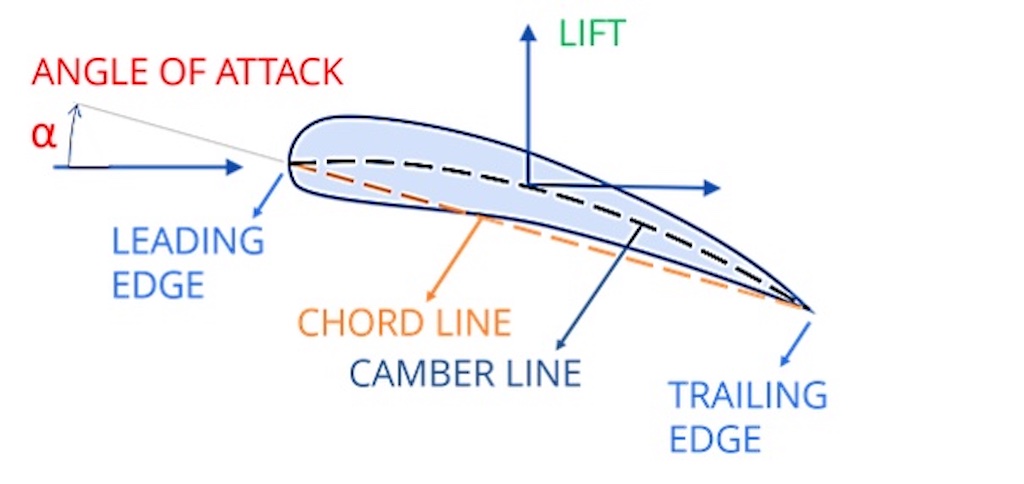

The aircraft’s AOA is the angle between the chord line of the wing and the relative wind. The chord line is simply the line between the leading and trailing edges of the wing and the relative wind is the airmass relative to the aircraft. The pilot can’t really see either of these but should have a pretty good idea based on the aircraft’s behavior.

Some aircraft will have an AOA indicator that, in my opinion, is the single most important instrument on any aircraft. Other aircraft, incredibly, will not have any such indicator but are likely to have a means of measuring AOA to trigger stall warning devices. In most systems, these devices can do nothing more than alert the pilot of an impending stall by shaking or nudging the stick or yoke. In some aircraft, the automatic systems can add thrust or even activate the flight controls if the pilot fails to. Not having an AOA indicator or any of the other devices saves money, of course.

The simplest way to measure AOA is to stick a calibrated vane into the relative wind and measure the angle. These devices can get stuck at an extreme angle, can become jammed if hit by a bird, or can simply fail mechanically. This can be problematic if it causes the pilot or any of the automatic systems to think there is a stall when there isn’t or to believe there isn’t a stall when there is. The solution is to add redundant AOA measuring devices and stall barriers, which of course adds cost.

Any aircraft that allows its flight control system to overrule a pilot’s decision or to take control from the pilot under certain circumstances should obviously have a high level of redundancy to prevent the aircraft from making a wrong decision. In my aircraft, a Gulfstream GVII, for example, the fly-by-wire system will reduce the AOA on its own should I pull back on the stick too far. Instead of one mechanical AOA probe we have four pressure probes which measure pressure above, below and to the side of each probe. This is the most redundant AOA system I’ve ever flown and may some day become the standard. For now, however, the standard appears to be two mechanical AOA vanes.

Thirty years ago, I was flying a Gulfstream III with two mechanical AOA vanes and two stall barrier systems. The problem is that if one system says the aircraft is in a stall and the other disagrees, what should it do? The answer was to do nothing, tell the pilot about the argument, and allow the pilot to decide. That idea, “let the pilot sort it out,” isn’t universal.

In Part 2 of this article, we discuss Boeing’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System and two fatal accidents of the Boeing 737 MAX 8.