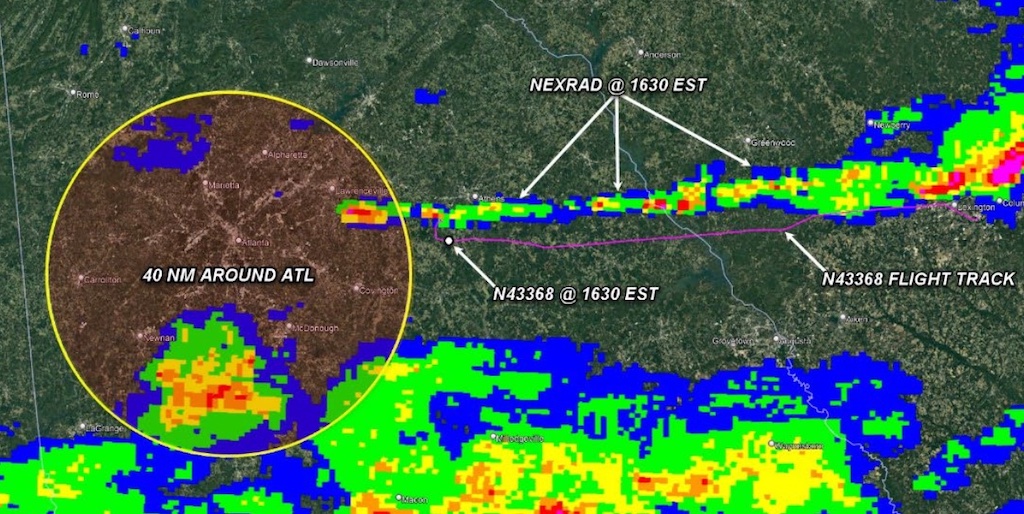

N43368 on National Weather Service WSR-88 radar.

It’s unlikely that there are any current pilots who don’t know there are delays in the transmission of weather radar to cockpit Next Generation Weather Radar (NEXRAD) displays. There’s ample guidance to airmen about display latency in pilot guides and industry literature. The NTSB issued a Safety Alert, SA-017, on “In-Cockpit NEXRAD Mosaic Imagery” in 2012 (revised in 2015) that explained latency. The FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge also discusses the subject, as does the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM).

Unfortunately, pilots who are NEXRAD-equipped sometimes still fly into thunderstorms. I found 13 accidents in the NTSB database with NEXRAD in the analysis, eight of which were classified as loss-of-control inflight. Several of these involved the pilot’s misinterpretation of the NEXRAD display. The most recent of these took place near Bishop, Georgia, on March 3, 2020.

The Piper PA-46-310P Malibu, registration N43368, was enroute from Columbia Metropolitan Airport (CAE), in Columbia, South Carolina, to Tuscaloosa Regional Airport (TCL), Tuscaloosa, Alabama, on an IFR flight plan. The pilot had received warnings about thunderstorm and heavy rain shower activity from Foreflight Mobile and the airplane was equipped with XM and Flight Information Services–Broadcast (FIS-B) weather information. The pilot had access to XM weather composite radar images and FIS-B weather radar imagery.

The airplane remained about 10-to-20 mi. south of a line of weather while cruising at 6,000 ft. MSL. The pilot contacted the Atlanta approach controller at 16:13 EST and was provided the current altimeter reading. The controller told the pilot he would have to be routed either north or south around the Atlanta area, and the pilot chose north. The Malibu was cleared to Tuscaloosa via radar vectors to the Logan intersection and then direct to Tuscaloosa.

At 16:28 the controller told the pilot there was a gap in the line in about eight miles and to fly heading three zero zero.

The pilot replied: “approach malibu three six eight that’s that’s pointing us straight into a [unintelligible] build up three six eight.”

After some discussion, the controller said: “and three six eight uh just heading three zero zero for now that’ll keep ya out of the moderate precip heading three zero zero.”

The pilot replied: “I thought I was gonna shoot this gap here, I got a gap I can go straight through three six eight.”

The controller said: “alright that’s fine november three six eight if that looks good to you I show you’re gonna enter moderate precip in about a mile and that will extend for about four miles northbound.”

A minute later the controller asked the pilot for his fight conditions, and he replied “rain.” That was his last transmission. The controller observed “XXX” in the N43368 data tag, and then informed the controller in charge (CIC) that he may have lost an aircraft.

Multiple witnesses saw the airplane descend to the ground and catch fire. The pilot and his two passengers were killed.

The accident pilot had a subscription to XM data and a Garmin GMX-200 display was found in the airplane. He had 1,178 hours and had flown his airplane in weather before. On a flight from Colorado to Texas, for example, he had noted in his logbook “dodging afternoon thunderstorms.”

The line of heavy weather was moving east at 25 kt. and the display the pilot was looking at could have been 10 min. old or even older. The gap he was aiming for wasn’t there.

Outdated Weather Information

The NTSB said the pilot had relied on outdated weather information on his cockpit weather display. The board didn’t say why it thought he ignored a controller’s vector through the buildups in favor of his NEXRAD display. Is there something else going on besides latency that would cause pilots to fly into dangerous cumulus clouds?

The FAA has done some research on pilot interaction with weather displays. In a 2004 study, the agency found that pilots spent more time looking at higher resolution images than at lower-resolution ones. They found that higher-resolution images are likely to encourage pilots to continue flights with the expectation that they can fly around or between significant weather features.

In a 2019 FAA study, researchers found that, on average, pilots underestimate the “out-the-window” visibility for a range of simulated conditions. The most accurate estimates of distance from cloud were within 1 nm of the cloud. The failure to assess current visibility conditions increased the odds of VFR-into-IMC flights.

In a 2020 study published in the journal Aerospace Medicine and Human Performance, researchers said: “Regarding interpreting radar displays, the results in this study parallel other research indicating that pilots struggle to interpret radar correctly.” The “technology itself can generate serious human performance decrements, and this may be occurring with respect to GA weather-related accidents.”

“Today, ample research exists demonstrating that NEXRAD technology, in particular, is not necessarily helping GA pilots to avoid hazardous weather,” the authors found.

Finally, in a Psychology Today article entitled “Digital Distractions: Energy Drain and Your Brain on Screens,” Richard Cytowic, a medical doctors, says: “The incessant, seductive presence of screens promotes sensation at the expense of thought, the amped-up pathways competing with the maturation of circuits normally destined to support social relationships and emotional intelligence.”

It seems that the very precision and vividness of our many digital devices increases their salience and encourages us to act without thinking. On our digital devices—cockpit displays, smartphones, tablets, computers, even TVs—the medium itself might be affecting our judgment.

We’re not going to stop using these amazing devices, but maybe we should start finding ways to tune them down or even tune them out. Our experience and judgment is hard-earned and not to be thrown away because of something on a digital display.