We practice some maneuvers in the simulator because they are just too dangerous to do in the airplane. For these, our performance must be automatic, almost unthinking, reactions that get us out of harm’s way until we have a few moments to catch up with the airplane. Consider an engine failure right at V1. Our reaction requires the right balance of multiple smooth but swift control inputs to keep the peas from rolling off the plate. Rudder must be added immediately to maintain track, and the need for rudder increases dramatically as the nose comes off the runway. Pitch control becomes critical, as we must capture V2 to V2 + 10 with one less engine’s thrust. Navigation depends on keeping the aircraft coordinated. Only once all this is done can we take a mental step back and survey the situation. If we practice this repeatedly in the simulator, we have a fighting chance of getting it right in the aircraft. Provided we keep our cool.

You might say the same thing about a missed approach initiated at minimums. The aircraft is headed downhill, and we want to reverse that while mentally switching from “I’m arriving” to “I’m departing” and getting the navigation right. Again, we practice this until it becomes automatic. You can probably add a rapid loss of pressurization at high altitude, a thrust reverser unlocked in flight, and just a few other flight maneuvers to this list of “immediate actions.” What about balked landings?

We practice those in the simulator all the time in the Gulfstream GVII. The pilot flying (PF) using the enhanced flight vision system (EFVS) spots the runway at 200 ft. above it, even though the pilot monitoring (PM) does not. He continues to 100 ft. If authorized to take it to touchdown, the PM spots the runway on his EFVS “heads down” displays and the crew goes further. Even without the technology, the crew might find themselves with the necessary visual cues to land when the pesky simulator instructor touches a button, and a truck pulls out onto the runway. “Go around!” The crew goes around and saves the day. The instructor pats them on the back and vectors them around for the next approach, having checked off yet another training requirement. An unintended consequence of all this is that pilots are conditioned to think they can do this routinely without too much trouble; this thought is reinforced in the debrief when nothing more is said about it. But can they? It turns out that there is a lot more to consider than merely going around; in reality, a balked landing is more complicated and riskier than a simple missed approach.

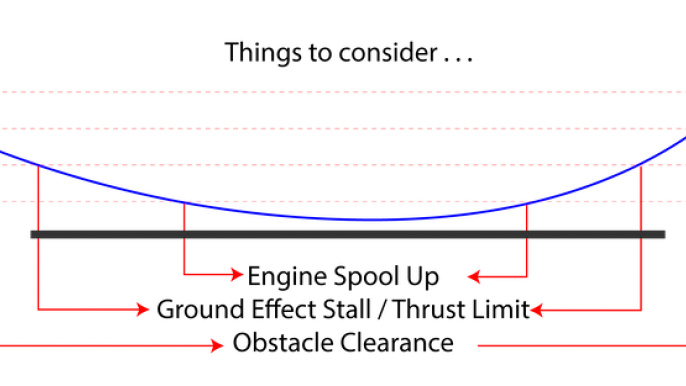

What do you have to worry about? The second you dip below the published decision altitude (DA) or go beyond the published missed approach point (MAP), lots. Your missed approach path has been checked against obstacles, provided you begin the missed approach no later than the DA or MAP. Once you've gone beyond those points, you could have a problem. We are taught early on that ground effect is a good thing, and that is mostly true. But it can be a very difficult thing to climb out of. Unless you are protected by a very intelligent flight idle system, bringing your throttles to idle significantly changes the balked landing decision process.

You cannot balk a landing, go through rote procedures and be guaranteed success. You need to have exceptional situational awareness if you hope to beat the obstacles, the influences of ground effect and the lag in your engine spool-up time.

Obstacle Clearance

When does a missed approach become a "balked" landing? I think of going beyond the DA as a decision to land, and reversing that decision means you intend to balk the landing. Going missed approach before the DA assures you of obstacle clearance, provided you follow the procedure. Once you've gone beyond the DA, you might clear the obstacles. But maybe not.

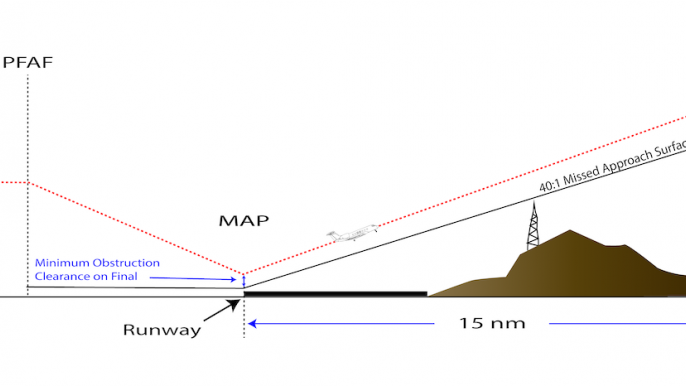

The U.S. Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS), FAA Order 8260.3E, requires that a missed approach procedure be established for each instrument procedure. A MAP is specified that “may be the point of intersection of a specific glidepath with a DA, a navigation facility, a fix or a specified distance from the PFAF.” There is a surface that begins over the MAP that rises at least 1-ft. vertical for each 40-ft. horizontal, or as needed to clear any obstacle for 15 nm. The location or altitude of the MAP may need to be adjusted to ensure no obstacles penetrate the missed approach surface. While it is more complicated than that, as pilots we know that if we begin our missed approach no lower vertically and no later horizontally than the MAP and climb at the minimum rate of climb or higher, we will be guaranteed obstacle clearance.

If you descend below a published DA or initiate your missed approach beyond the MAP, those guarantees go away. In theory, once you go beyond those points, you are no longer on approach, you are landing. But that theory only holds true partially, as the following examples show.

Let’s say you are on an instrument landing system (ILS) approach and at the 200-ft. DA you spot the approach lights and nothing more. Under 14 CFR 91.175(c) you can continue to 100 ft. above the touchdown zone elevation (TDZE); you are still “on the approach.” If you spot the red terminating bars or the red side row bars you can land. If you don’t, you go around. But what about obstacle clearance?

If you are trained, equipped and authorized to use an EFVS under the provisions of 14 CFR 91.176(a) you could take the aircraft even lower before deciding to go around. Once again, obstacle clearance is no longer guaranteed.

But you don’t need an ILS or EFVS to be put into this situation. From any approach, and after you’ve made the decision to land, you could find yourself just about ready to touch down when you spot a vehicle or animal on the runway, or an aircraft malfunction convinces you to balk the landing.

In all three cases, for most airports, you probably won’t have a problem. If the normal departure procedure is obstacle free, “chances” are the missed approach procedure will be as well. But how do you know? In the planning stage, there are a few places you can look to alert you to a problem so you can come up with a plan.

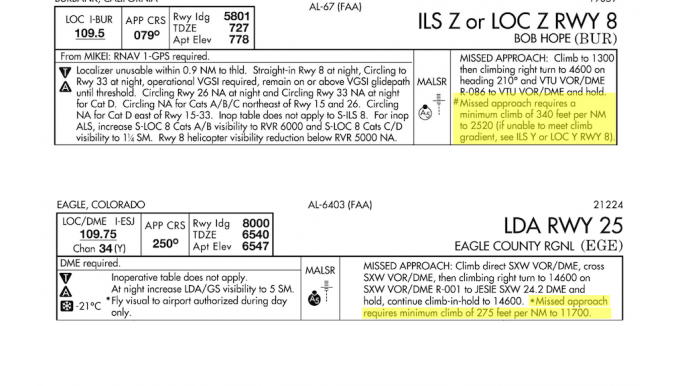

First, a well-designed procedure will tell you flat out that you will have a problem. The Juneau International Airport (PAJN), Alaska, LDA X Rwy 8 does just that: "CAUTION: Any go-around after passing MAP will not provide standard obstruction clearance." Second, when there is a potential problem, a procedure might steer you toward a more doable option. The Bob Hope Airport (KBUR), California, ILS Z or LOC Z Rwy 8 missed approach text warns you of the steep missed approach climb gradient but also tells you to see the ILS Y or LOC Y Rwy 8 if you’re unable to meet that requirement. Third, sometimes just seeing a higher-than-standard gradient to a high altitude tells you obstacles could be a problem, as with the Eagle Country Regional Airport (KEGE), Colorado, LDA Rwy 25. Finally, sometimes a clue is in the FAA’s Terminal Procedures Publication, letting you know there’s a preferred “one way in and out” route common in many valley airports, such as McCall Municipal Airport (KMYL), Idaho, or Aspen-Pitkin County/Sardy Field Airport (KASE) in Colorado.

Obstacle Clearance Options

If you know the missed approach procedure will not guarantee obstacle clearance if executed below the DA/beyond the MAP, it may be a good idea to devise an alternate plan based on the runway's standard instrument departure (SID) or a published obstacle departure procedure (ODP).

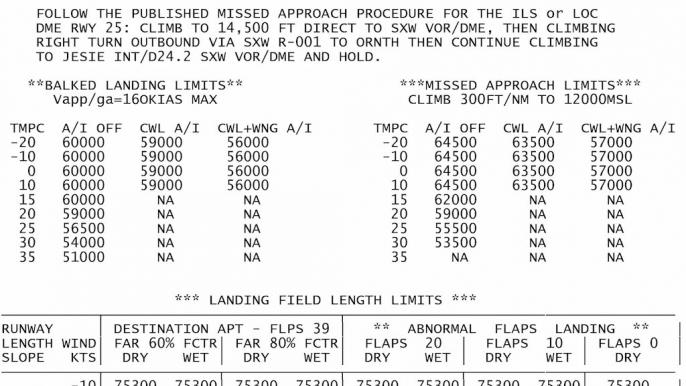

Some runway analysis companies will offer balked landing procedures with aircraft and weather limitations, or simply give you the aircraft configuration and environmental limits of the published procedures if executed as late as the runway touchdown zone. The procedure shown in the illustration is for a Gulfstream GV on approach to Eagle County Regional Airport.

With either option, you must remember that a clearance for an instrument approach is also a clearance to fly the published missed approach. It does not include a clearance to fly any alternate procedures unless you let ATC know your intentions ahead of time and they approve them. There is a school of thought that if you must balk the landing, you can declare an emergency and ATC will have no choice but to give you your way. Do you really want to have to do that with everything else going on during a balked landing? Do you really want to rely on everyone else getting out of your way? My advice: If you need alternate balked landing procedures, let ATC know before you are cleared for the approach.

Also, if your balked landing procedure is different than your published missed approach, you might consider entering it into your FMS as a "secondary flight plan" if you have that capability. If you plan on doing this, you should be well practiced at making the change. When you are low to the ground and your workload is high is no time to learn how to do this.

Finally, remember that sometimes you cannot do what you want to do and must simply raise your weather minimums or reduce your approach weight to make it possible. If you cannot guarantee obstacle clearance after going below the approach's published minimums, then don't do that until you are certain you can land.

The next part of this article will examine ground effect.

Comments