Viewpoint: Delayed by Dictate

In “Viewpoint: Not All Airplanes Fly Alike” (May 19, 2022), James Albright ably highlights FAA’s mindset of systemic reluctance following its flawed certification and post-accidents issues involving the Boeing 737 MAX.

However, the agency problems to which he refers are, unfortunately, even larger. Senior management at two major general aviation companies recently confided in me that they are suffering inordinate delays on certification projects due in part to a post-MAX over-reaction within the FAA. Those delays, they say, are near crisis levels.

But that’s nothing new. In fact, our small company, General Aviation Modifications, Inc. (GAMI), has endured repeated FAA-induced delays for the last 12 years as we invested in researching, creating, testing and proving a lead-free, high-octane aviation gasoline suitable for the entire fleet. And those delays continue. Indeed, what we’ve experienced since just last November is a saga that underscores the agency’s repeated failures to follow its own policies, guidance and rules (https://youtu.be/FCMvXZejwzY).

In a recent conference call, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) atmospheric emissions group stated that later this year it will finally issue a notice of an Endangerment Finding against 100LL aviation gasoline—the only fuel still containing lead, a poison. Thus, the Spark Ignition Piston Powered Aircraft world faces an existential crisis Right Now! and not years in the future.

Notably, this past March, the Wichita Aircraft Certification Office (ACO) formally informed GAMI that we had successfully completed all the FAA-required certification activities, fully complied with all regulations, and that it was ready to sign and deliver a pair of “fleet-wide” Approved Model List (AML) Supplemental Type Certificates (STC) for our G100UL unleaded avgas. Great. At long last. Accordingly, GAMI is working with a major oil company that wants to start production and distribution of G100UL.

Unfortunately, the Wichita ACO has yet to sign those documents. Why the delay? Because FAA headquarters in Washington refused to let its Wichita ACO manager perform that routine administrative function. And why is that? No one outside 800 Independence Ave. knows for sure, but one can speculate.

Before his recent retirement, a very senior FAA certification engineer observed that the root cause of the MAX fiasco was the failure of agency management to follow the recommendations of its own 737 MAX project certification engineers.

I submit that the root cause of what’s become the G100UL convolution and obstruction is…wait for it: The failure of FAA management to follow the recommendations of its own G100UL avgas certification engineers!

Then, too, there’s the matter of money. In 2012, the FAA started its Piston Aviation Fuels Initiative (PAFI) whose goal was to find (at taxpayer’s expense) an unleaded, high-octane replacement for 100LL. That program slogged along for eight years before FAA finally admitted to failure in identifying any workable unleaded avgas solution. Estimated cost to the taxpayers for the botched effort? Between $45 million-$80 million (there is no clear accounting).

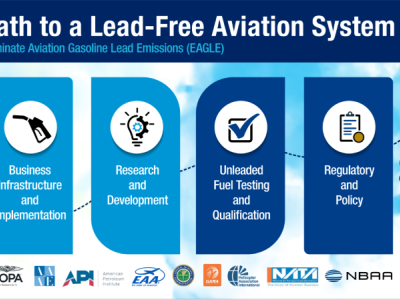

As Ronald Reagan once quipped, you can never get rid of a failed government program. Confirming that truism, earlier this year the FAA announced the launch of EAGLE, a nifty acronym for its Eliminate Aviation Gasoline Lead Emissions initiative—think, PAFI 2.0. But now the agency wants Congress to fund this unnecessary redo for up to nine more years and at a cost of some $110 million! All that to solve a problem that disappears with a signature in Wichita and at zero expense.

Following the money also leads to significant financial interests lobbying to ensure certain major oil companies continue to sell their high-profit leaded avgas until the EPA bans the poison.

Some airport operators aren’t waiting for EPA to act and have already banned the sale of 100LL. Without a fleet-wide, unleaded replacement fuel, such moves raise concerns about operational safety, which is supposedly FAA’s highest priority. Heaven forbid that a piston powered aircraft belly into a school yard, its tanks empty due to the unavailability of high-octane avgas.

There has been a hopeful development, however, in the newly appointed head of all FAA Certification. People at companies who worked with her when she was an FAA Certification Engineer give her high praise. Fingers crossed that she exercises her new authority to resolve the incessant delays of general aviation certification projects and force FAA bureaucrats “to stop loving the problem.”

One of those problems—the ever elusive, high-octane, unleaded, fleetwide avgas—can be solved by simply allowing FAA’s very experienced, seasoned and highly competent engineers and managers at the Wichita Aircraft Certification Office, to do their jobs. Sign those documents and the problem disappears.

George Braly is an aerospace engineer (Brown University ’70) and an FAA Designated Engineering Representative (DER) with authorizations in engines, powerplants and flight test. He has over 10,000 hours of flight time in a wide variety of general aviation aircraft.