Trade truces and low fuel prices underpin brighter outlook for airlines

For airlines in general, 2019 was a “tough” year; for cargo carriers in particular, it was “miserable,” IATA executives acknowledged in their annual industry summary and outlook, presented in Geneva in mid-December.

With trade wars biting into business confidence and having a direct impact on the air transport industry, IATA again revised downward its forecast for the net profit that the world’s airlines will post in 2019. Although the industry as a whole is expected to post its 11th consecutive net profit in 2020—a trend that is relatively new in airline history—the level of profitability is falling. Neither the 2019 nor the 2020 profit forecasts are expected to reach the 2018 collective net profit of $32.3 billion. And the gap between those 20 to 30 airlines that are consistently profitable and those that struggle financially is growing.

The airline industry will produce a collective net profit of $25.9 billion for 2019, revised down from IATA’s forecast of $28 billion made in June, which was a downward revision from what now looks like a bullish $35.5 billion prediction in December 2018.

Trade tensions and weaker global GDP growth of 2.5% slowed trade growth to just 0.9% versus the 2.5% anticipated in June. That had a particularly negative effect on the air cargo business and also softened passenger demand, IATA chief economist Brian Pearce said. On the plus side, operating costs did not rise by as much as anticipated—3.8% versus the 7.4% forecast in June—but not by enough to offset the weaker revenue.

For 2020, IATA is forecasting a $29.3 billion net industry net profit and expects to see return on invested capital improve slightly from 5.7% in 2019 to 6%. Total revenue for 2020 is forecast to climb 4% to $872 billion from $838 billion expected for 2019. But operating expenses are expected to climb at almost the same rate, by 3.5% to $823 billion in 2020 from $796 billion this year. RPK growth will be flat, at 4.1% in 2020 and 4.2% in 2019, with both numbers below historical trends.

Passenger numbers in 2020 are expected to increase 4% to 4.72 billion in 2020 from 4.54 billion this year, while freight tonnes carried should improve slightly to 62.4 million in 2020 versus 61.2 million in 2019, a 2% uptick.

“It has been a pretty miserable year for the cargo business—their worst performance since the [2008-2009] global finance crisis,” Pearce said. Trade wars are mostly to blame, but IATA, in line with general industry economists, believes there will be more stability in 2020.

“Trade wars are hurting US consumers and while it’s difficult to say what will happen, the logic says there will be a continuing truce, not least because China has been giving some concessions,” Pearce said.

News broke shortly after the IATA forecast was published that the US Trump administration had reached agreement with Beijing on a “phase one” trade deal that signaled such a truce and would lift many of the tariffs. Details were scarce, however, and skeptics questioned how quickly the deal would take effect. Nevertheless, IATA’s working assumption—similar to that of the International Monetary Fund and the World Trade Organization—is that a trade truce will hold in the lead up to the US elections in November 2020. If that is the case, stronger economic growth in 2020 should produce a modest rise in international trade growth, from 0.9% in 2019 to 3.3% in 2020, and the expectation is that there will not be a recession. “That should bring some respite to the cargo business,” Pearce said.

IATA now expects cargo volumes to return to modest growth in 2020 at 2%, although that will still be well below freight’s long-term average growth rate of roughly 5%.

“The recovery remains fragile, with risks tilted to the downside. It is much easier to identify ways for things to go wrong than ways they’ll be better,” IATA deputy chief economist Andrew Matters noted.

A strong result for British prime minister Boris Johnson in the December UK elections—giving his Conservative party a majority—means that the country’s split from the European Union is expected to happen in 2020. But while the economic effect of Brexit has still to play out, Pearce said airlines have found workarounds to ensure connectivity stays in place.

Another positive for 2020 is that oil prices look set to stay relatively low through the year, IATA said. Supply is plentiful, while demand is weak—a combination that is expected to keep Brent crude prices stable at an average of $63 per barrel. On that basis, overall fuel costs for airlines could fall to $182 billion, or 22.1% of operating costs, versus 23.7% in 2019, IATA said.

Regional markets and profitability

The strongest air travel growth this year has been in the domestic China market, at 8.5%. Other emerging markets, such as Eastern Europe and within Asia, also grew 7%-8%. Europe saw 7.5% market growth, but that was driven entirely by the Eastern Europe market and without it, growth would have been less than 3%.

The profit picture is mixed for this year and next. Airlines in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America are all expected to lose money in 2019, although Latin America is forecast to return to profit in 2020.

North American carriers will again lead the profitability pack and are expected to post a net profit of $16.5 billion in 2020, down slightly from $16.9 billion in 2019. That represents a net profit of $16 per passenger—double the level of six years earlier. Net margins are forecast to dip slightly, from 6.4% to 6%, because of rising capacity and decline in yields, but breakeven load factor will hold steady at 58.9% thanks to ancillary revenue.

European carriers are forecast to post a $7.9 billion net profit in 2020, up from $6.2 billion in 2019. Breakeven load factors are the highest in this region, at just over 70% in 2019 and 2020, because of pressure on yields from the competitive market and high regulatory costs. The net profit uptick forecast for 2020 is based on stable fuel costs and cutbacks in airline capacity expansion plans. For 2020, airlines are expected to make $6.40 per passenger—a 3.6% margin—versus $5.21 in 2019.

Asia-Pacific carriers, helped by a modest recovery in world trade and air cargo, are expected to post a $6 billion net profit in 2020 versus $4.9 billion this year. They were the most exposed in 2019 to the impact of world trade tensions between the US and China and between Japan and Korea. The ongoing civil disruptions in Hong Kong have also reduced travel and cargo demand. With an anticipated world trade recovery, average profit per passenger among Asia-Pacific airlines is expected to grow from $2.92 in 2019 to $3.34 in 2020, with net margins increasing from 1.9% to a still-thin 2.2%.

Middle Eastern airlines are continuing their restructurings and should see some rebound next year after a very weak 2019. But they will remain in the red next year, albeit posting a smaller loss of $1 billion compared with 2019’s $1.5 billion. Their losses per passenger should decline from $6.84 to $4.48.

Latin American carriers should post a small profit of $100 million in 2020 versus a $400 million loss in 2019. Performance varies from country to country, and individual nation and airline fortunes can quickly flip. The region’s airlines are particularly vulnerable to government policies that view them as “cash cows.” Some of the world’s highest aviation fees and taxes are in Latin America. After losing $1.32 per passenger in 2019, Latin American carriers should squeeze out a $0.42 profit per passenger in 2020—a 0.3% margin.

African carriers, operating within another high government taxes and fees environment, are expected to post losses of around $200 million in 2019 and 2020. Although breakeven load factors, at around 58%, are low in the region, few airlines are able to achieve adequate load factors, and this remains one of the world’s weakest regions in terms of financial performance. Airlines are expected to lose $1.93 per passenger in 2020 versus $2.13 in 2019.

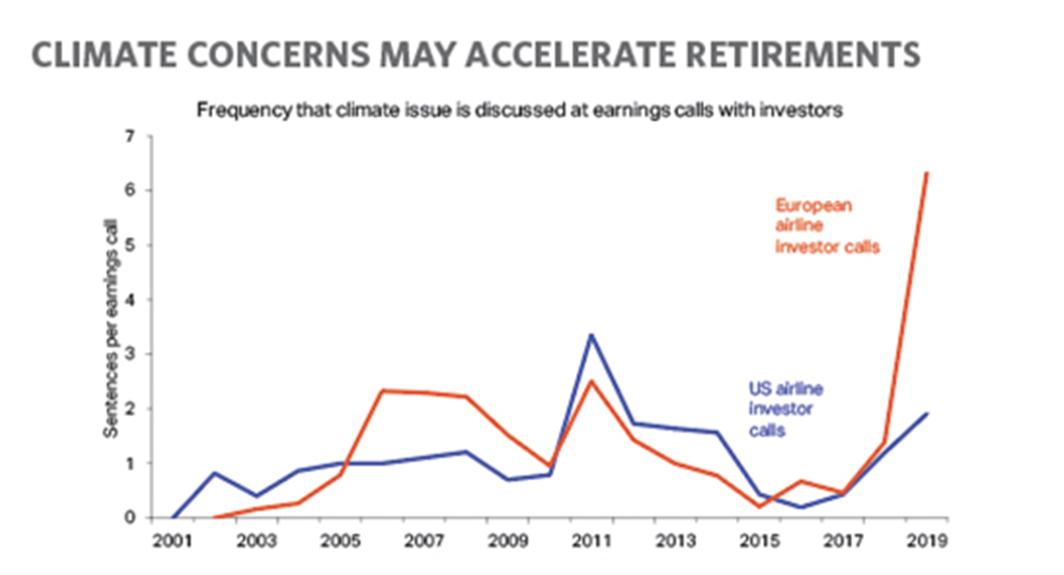

One area of concern for the 2020 outlook centers on a potential surge in capacity when the more than 2,100 Boeing 737 MAXs affected by that aircraft’s grounding since March start to be delivered. At 7.5% of the fleet, those MAXs represent an addition of more than two percentage points. “That’s a lot of new capacity to swallow,” Pearce noted. “But we suspect it won’t be one for one; there will likely be some rescheduling and it will depend on retirements. We expect to see an acceleration of retirements because airlines want more fuel-efficient aircraft and because of the climate issue.”

The big unknowns are when the MAX will be recertified globally and how fast the aerospace supply chain will be able to get the aircraft back into the market. Even so, there is a possibility that capacity growth, which slowed substantially in 2019, could outstrip demand.

Comments