Does a Next-Generation Airliner Make Business Sense?

by Frank Coleman III

with John Moore, Niklas Schumacher, and Tore Johnston

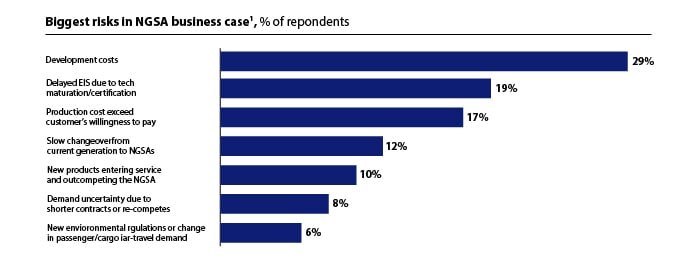

In April, Airbus CEO Guillaume Faury told shareholders that despite an environment that is “complex and fast-changing”, the company plans to launch a successor to the A320neo family by the end of the decade for entry into service in the second half of the 2030s. Faury projects confidence, but a significant portion of the broader commercial aviation supply chain has questions about the business case for a Next Generation Single Aisle (NGSA) aircraft. In the most recent McKinsey & Company – Aviation Week survey of over 135 firms, a majority cited concerns about development costs – up to $25b or a ~10-12 year payback – as the top risk to the NGSA business case, with technical feasibility following closely behind.

In 2024, McKinsey partnered with Aviation Week to survey commercial aerospace leaders across the entire value chain (Airframe and Engine OEMs, Suppliers, MROs, Operators, and Lessors) regarding their ability to meet current demand and their outlook for future aircraft, future technologies, and the nature of demand. We had expected an extended path to ramp-up for current generation narrow bodies and risk in the path to NGSA, but surprisingly 84% of last year’s respondents predicted that a NGSA aircraft would be fielded by 2035 or before.

An extended ramp-up timeline without a corresponding lag in NGSA would lead to what we called the “messy middle”, and many questions for suppliers – such as how to prioritize investment and human capital between current gen and next gen development, how to prioritize, and how to pay back the investments made in ramp-up.

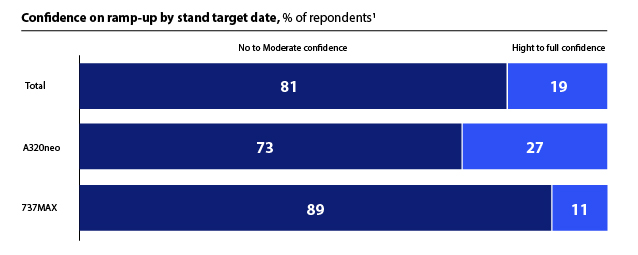

This year’s respondents continued to be tepid on the prospect of OEMs achieving their current generation production goals. On average, approximately 81% of those surveyed expressed zero to moderate confidence in Airframers’ ability to hit their production targets for 2026 and 2027. This suggests significant supply chain investments will be needed in current generation production for at least the next two years.

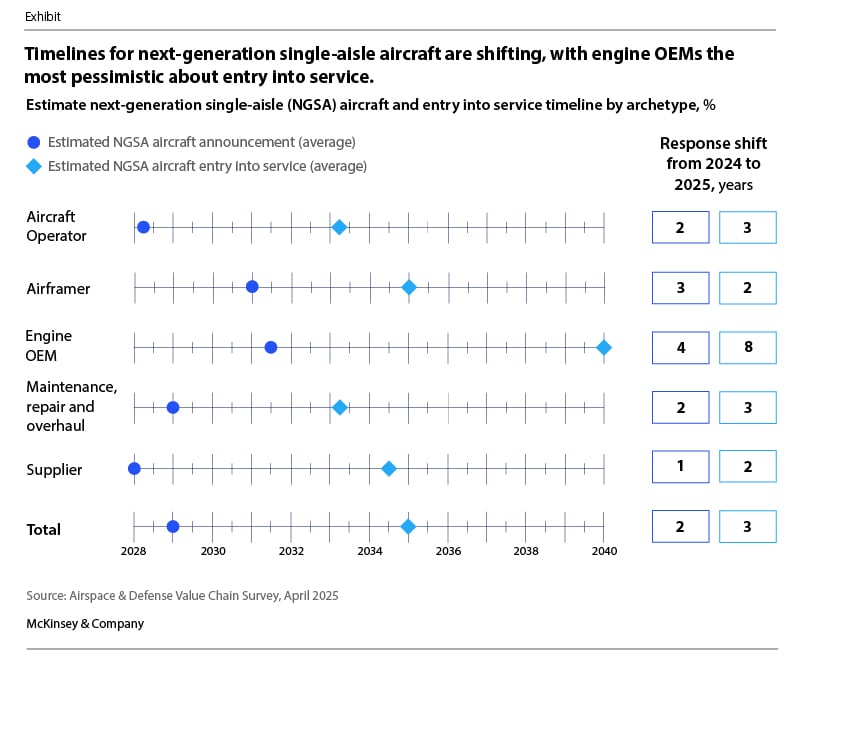

A complication from this delayed ramp is an even dimmer view on the timeline for NGSA, with average timelines shifting about 3 years to the right compared to last year. In short, the once ambitious timeline NSGA seems to be stagnating.

We believe this hesitancy reflects growing recognition across industry that next generation airliners will cost substantially more than today’s aircraft and feature longer development timelines. Current estimates suggest that an evolutionary NGSA will deliver a less-than-dramatic 12% increase in fuel efficiency over present narrowbodies.

12% is meaningful, but not exactly revolutionary. The problem is that respondents (notably engine OEMs and suppliers) estimated that the NGSA’s production cost may be on the order of 30% higher. There is a massive gulf between the expectations (and, we believe, willingness to pay) of operators and what the supply chain believes it can deliver. Well over one-quarter of aircraft operators said they were willing to defer fleet renewal for a decade or longer if their stated ROI on a new platform could not be met.

The flying public has enjoyed advances in aircraft technology over the last five decades at greatly reduced (real) cost, despite a long line of technological advances in range, comfort, and efficiency.

That trend could be ending, and it leads us to ask a different question: Does demand from operators match the economic realities of designing and building a cleansheet narrowbody aircraft, and can the business case close?

Based on the survey and a higher input cost environment in the future, we hypothesize that the current business case doesn’t close, and our view is that net zero ambitions alone will not be enough to support the business case for an NGSA. Industry players will be faced with significant strategic choices as the timeline for NGSA shifts towards 2040 or beyond.

Misalignment

Airframers have for years touted visions of lower- or zero-emission aircraft utilizing technologies such as hydrogen or hybrid-electric propulsion and airframe configuration changes such as truss-braced wings or blended wing-bodies.

Until recently, both Airbus and Boeing planned to fly sustainable demonstrator aircraft with these attributes by 2035. However, a more pragmatic view has emerged over the course of this year as both major OEMs announced significant delays or cancelations relating to these tech demonstrators.

Last year, suppliers indicated significant uncertainty in which technologies to invest in. With the implied delays in NSGA, the urgency may be reduced but the feeling is still evident in survey responses on investments in NGSA engine technology. Respondents projected the need to invest in conventional turbofan, open rotor, or hybrid-electric propulsion choices in roughly equal shares. This indicates there is no consensus on the technical direction of NGSA propulsion.

However, when questioned about performance, nearly half of OEMs and suppliers say they expect NGSA propulsion efficiency gains of 10% or less over current platforms, suggesting that engine investment is most likely to center on conventional turbofan technology.

This uncertainty on how advanced NGSA airframes or new engine technology need to be is reflected in the expected entry into service (EIS) of next generation aircraft. Across the value chain the timeline has shifted to the right by 3-4 years on average. Over one-third of those surveyed posit EIS by 2034 or later. Engine OEMs are particularly misaligned with airframers, operators, MROs and suppliers. Their view has shifted the most to the right (8 years on average) and most expect NGSA EIS in 2040 or later.

Furthermore, there is ample evidence from the industry’s R&D behavior that NGSA isn’t a top priority: over half of those surveyed report moderate to no understanding of the technologies needed to support NGSA, and 85% of respondents indicate they are allocating less than 20% of their R&D budgets to NGSA-related technologies this year.

Can the Industry Close the NGSA Business Case?

As commercial aerospace emerged from the pandemic, the general narrative postulated that production rates would recover slowly but steadily, the industry would hit airframer production targets, and build back the sustainable cash flow generation needed to fund investment in Next-Gen Single Aisle.

Instead, we see an environment in which the value chain is still pouring investment dollars into meeting the ramp-up. Some lingering challenges are ones the industry has faced for years (e.g., supply chain resilience, constrained materials, labor, cost inflation) and others are newer – such as prolonged aircraft certification timelines. Recent development programs exemplify this trend. Each of these challenges has the potential to extend and expand the budget for a new development program.

The flow of investment to meet current production, combined with delivery delays for narrow and widebody aircraft, raises a question: Will Suppliers or Airframers be sufficiently resourced to pay for advanced technology investments in NGSA?

When to plan for NGSA investment is a vexing question as well. Suppliers cannot afford to be left behind in terms of investment, but if they invest today, they risk both making the wrong technology choices and incorrectly guessing airframer timing. Alongside flagging confidence in the NGSA timeline, this conundrum is prompting paralysis.

Reluctance to invest in next-gen R&D may simply reflect expectations of cost increases above and beyond projected yields in performance / efficiency improvement. If this mismatch holds, it will be tough to justify investment in a NGSA aircraft.

This leaves the industry with a conundrum. Its desire to advance more efficient commercial transport looks unsupportable if the actual cost of an NGSA far outweighs the ROI of improved performance.

Operators face a difficult question, then, in whether they believe consumers are truly willing to pay a premium for the next generation of air travel. If not, operators may elect to stay with current aircraft types for longer until the NGSA cost-benefit equation comes into balance (either through advances in performance or product cost).

We see two feasible scenarios:

- Taking an optimistic view, a modestly ambitious NGSA aircraft enters service mid to late next decade, with a familiar design and moderately improved performance – with enough operators willing to bet that it will differentiate them in the airline market

- Alternatively, the inability to close the business case causes NGSA to be further delayed, and operators stick with current-generation aircraft even longer

In the latter scenario, we see the fundamental risk that the industry cannot close the NGSA business case without substantial regulatory incentives or travelers willing to pay more to accommodate structural change in the value chain.

Survey respondents agree, with well over half ranking subsidies or alternative funding mechanisms as "important" to "fairly important" to support NGSA development.

How to win if the NGSA continues to slip to the right

Knowing this risk, the operative question for commercial aerospace value chain is how to thrive in an environment less focused on new aircraft programs. Our view is that the next five years is not a NGSA plan – rather, it should center on transitioning from legacy aircraft to a fleet dominated by today’s “next gen” (MAX, neo) and strengthening positions for the long haul on these programs.

OEMs should start with a clear and realistic message to their supply chain on the refined vision for NGSA and an emphasis on getting the value chain for current programs back to a healthy state. From there, OEMs will need to determine the right moment to announce their NGSA development programs and the necessary partnerships with suppliers and customers to close the business case.

Operators should consider willingness to pay in their market and the likelihood of regulatory pressure and share these views candidly with airframers. We anticipate many operators will plan for the longer haul on their ‘next gen’ fleets. Investments such as in MRO capabilities or broader fleet renewal at the current state of the art may be easier to justify in a world where NGSA is fifteen years away, rather than ten.

Suppliers should take this moment to invest in next generation engineering (e.g., digital twin, MBSE) and production capabilities (incl. SIOP and helping their own suppliers) – both to meet the ramp and to prepare a competitive cost profile for another ten to fifteen years of full rate production. Like operators, these investments may be easier to justify given the extending timeline but will be critical to competitiveness. Suppliers who have been hesitant to negotiate likely also have an opportunity to negotiate stronger positions on current-gen programs now that NGSA may no longer be a near-term trade “carrot”.

In conclusion, we believe that until there is a solution to this business case, NGSA will continue to shift to the right and players must develop a pragmatic near-term strategy. For most, that will involve sound execution during the current narrowbody ramp-up and consolidating both commercial contracts and cost structures for the long haul on current generation programs. Across all segments, the players who do this well will be the ones best positioned to shift gears quickly when NGSA becomes a reality rather than a promise.