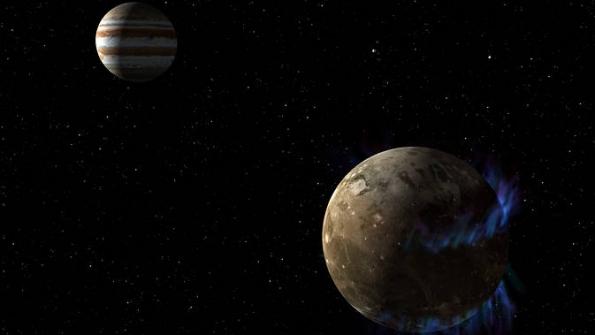

Rocking Aurora Point to Large Ocean on Jupiter's moon Ganymede

Images from the Hubble Space Telescope appear to confirm suspicions that Jupiter's moon Ganymede, the largest natural satellite in the solar system, has a vast sub-surface saltwater ocean.

Submerged beneath a 95 mile-thick mostly ice layer, the ocean's depth is estimated at 60 miles, 10 times greater than the Earth's.

The findings place Ganymede alongside Europa, another Jovian moon, and Enceladus, a moon of Saturn's, as recent candidate bodies among the solar system's outer planets with watery environments potentially suitable for biological activity. Earlier this week, scientists publishing in the journal Nature described a deep ocean below the icy crust of Enceladus, a body of water with a heat source at a rocky core that drives a geyser like spray at that moon’s south pole. The discovery was based on observations from the NASA, European Space Agency Cassini mission.

Europa has been the focus of a possible new NASA mission for several years, with strong support from Congress as well as planetary scientists. NASA's Europa Clipper mission is likely to receive formal approval this year.

"In its 25 years in orbit, Hubble has made many scientific discoveries in our own solar system," noted John Grunsfeld, associate administrator of NASA's Science Mission Directorate, in a statement. "A deep ocean under the icy crust of Ganymede opens up further exciting possibilities for life beyond Earth.''

Shuttle astronauts upgrade the Hubble Space Telescope. NASA

The new findings were published Thursday in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics.

Suspicions of a subsurface ocean at Ganymede date back to the 1970s.

Joachim Saur, a researcher from the University of Cologne in Germany, devised a strategy for using the HST to investigate further. The strategy relied on another unusual feature of Ganymede's, a magnetic field.

The moon's magnetic field is responsible for glowing aurora at Ganymede's north and south poles. At the same time, Ganymede is close to Jupiter's own dynamic magnetic field. When Jupiter's magnetic field changes, the aurora on Ganymede rock back and forth.

The rocking motion enabled Saur and his team to train Hubble and its ultraviolet optics on Ganymede to determine the presence of saltwater beneath an icy crust.

"I was always brainstorming how we could use a telescope in other ways," said Saur. "Is there a way you could use a telescope to look inside a planetary body? Then I thought: the aurora!"

The presence of a saltwater ocean on Ganymede should counter Jupiter's magnetic field, suppressing the rocking of the aurora, he reasoned. By gauging the resistance, Saur and his colleagues were able to make their ocean estimates.