Besides the technical and financial details NASA and Axiom Space had to work out to conduct a four-member private spaceflight to the International Space Station have come new questions about liability such as who is responsible if a passenger breaks the toilet?

Much of the station’s laboratory equipment will be off limits to the upcoming Axiom-1 (Ax-1) crew, a privately funded mission bankrolled by three of the passengers. Axiom is paying for the fourth seat aboard a SpaceX Crew Dragon capsule and flying former NASA astronaut Michael Lopez-Alegria, who now works for Axiom. The Ax-1 launch, which is provided by SpaceX under a separate contract with Axiom, is scheduled for no earlier than April 6.

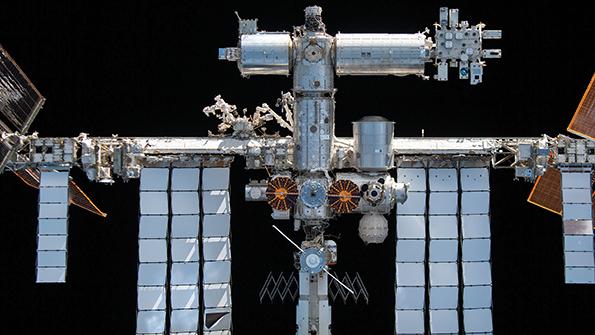

Calculating costs for some of the other station systems that the Ax-1 crew will use, such as carbon dioxide scrubbers, is not practical—at least not during these early days of private travel to the International Space Station (ISS), which is owned and operated by five government space agencies.

- Axiom must buy $10 million liability policy

- First U.S. commercial flight to the station is considered a pathfinder

After a year of discussions, NASA tallied up the potential risk to insurable ISS property and presented Axiom with a requirement to purchase a $10 million liability policy, Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight at NASA headquarters, tells Aviation Week.

Axiom was also required to buy a $5 million personal injury insurance policy in case the private astronauts are injured during the mission.

“For the property number, we essentially looked at the things the private astronauts could potentially ‘break’ and the potential costs for fixes,” McAlister says. “We settled on $10 million as a reasonable amount to mitigate the risk to NASA and the ISS.”

Private astronaut mission liability is based on six considerations: FAA licensing, cross-waivers, private astronaut waivers, insurance protection for a private astronaut injury, insurance protection for NASA, international partners and property coverage, and third parties.

“There may be variances in the framework, depending on the specific mission profile,” notes McAlister.

NASA considers the Ax-1 mission a pathfinder in an increasingly complex web of business ventures with private companies, many of which are developing and operating their own space projects alongside—and in some cases in partnership with—the U.S. space agency.

NASA is depending on commercial services and platforms in low Earth orbit (LEO) to meet its needs for human research, technology development and inflight crew testing after the ISS is retired. The Biden administration supports extending the station to 2030, which would provide NASA about two years to transition its LEO research programs to privately owned and operated outposts, currently under development. The ISS is authorized through 2024.

“Enabling the Ax-1 mission has been an important step to stimulate demand for commercial human spaceflight destination services so that NASA can be one of many customers in low Earth orbit,” McAlister says. “Setting expectations for all aspects of this private astronaut mission has been a lot of work, since this particular type of mission has never been done before.”

In addition to liability issues, NASA had to develop a commercial pricing policy, establish a code of conduct for private astronauts, set training requirements, obtain approvals from ISS partners and address and approve commercial activities.

Ax-1 is a trial run as well for Axiom, which will not make a profit from the venture. The Houston-based company, which is headed by former NASA ISS program manager Michael Suffredini, is developing a series of modules that will first be attached to the station and later separated to operate as a free-flying outpost owned and operated by Axiom.

Precursor missions such as Ax-1 present opportunities for Axiom to build its relationship with NASA and the ISS partners while showcasing services other countries, companies and agencies can purchase.

Axiom stands to make a bit of money from NASA from the Ax-1, as the agency is paying about $6.6 million for Axiom to launch and return two Polar refrigerator/freezers for NASA science samples and to return an empty nitrogen tank.

NASA will deduct about $2.9 million for services it is providing to Axiom for the Ax-1 mission including crew supplies, cargo delivery to space, storage and in-orbit resources for daily use. The fees are based on NASA’s 2019 pricing policy, which was revised last year to more accurately reflect the true cost of providing ISS services and commodities to private travelers.

Axiom also will be reimbursing NASA for use of facilities at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, the Kennedy Space Center in Florida and other services. Separately, Axiom’s transportation contractor SpaceX has a reimbursable Space Act Agreement with Kennedy for launch services.

Axiom does not expect to turn a profit from the private astronaut missions until it can fly four, rather than three, paying passengers. “We’re investing in the process,” says Mary Lynne Dittmar, Axiom executive vice president for government operations.