Putting BizJets Through Their Paces

September 21, 2018

Gulfstream G500

Disruptive change is one of the world’s most overused terms. But it’s appropriate when applied to the Gulfstream G500. This aircraft flies higher and faster than almost all current or known future competitors. Suddenly, cruising at a mere Mach 0.80 seems so 20th century. The G500’s economy cruise speed is Mach 0.85, the new standard for most next-generation large-cabin business aircraft, as well as new long-range Airbuses and Boeings.

Legacy 500

The Brazilian planemaker positioned this business jet as a midsize aircraft, because of its 3,000-nm range and $20 million base price. It would like all to believe its main competition is the Bombardier Learjet 85, Cessna Citation Sovereign and Gulfstream G150, among others in that category.

Yet, apart from measures of range and price, the Legacy 500 actually steps up to the super-midsize class, competing in many ways with the Bombardier Challenger 300/350 and Gulfstream G280. This aircraft is the result of 1,000+ engineers working on the clean-sheet design.

Pilatus PC-12 NG

There’s no mistaking a 2016 Pilatus PC-12 NG from earlier versions of the aircraft. The third iteration of this 22-year old model sports a five-blade Hartzell prop with scimitar-shaped blades made of black carbon fiber. Because of the new prop’s computer-refined blade airfoil and thin chord section, it’s more efficient at converting torque into thrust in all phases of flight than the aluminum Hartzell four-blade prop it replaces. It’s also 7-lb. lighter, so it has less rotating inertia.

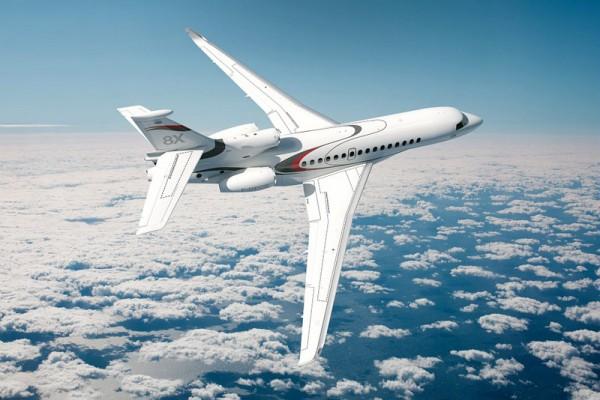

Dassault Falcon 8X

The Falcon 8X represents something of a paradigm shift for Dassault. This is the first time in the company’s history that it has stretched one of its existing Falcon Jets to create a derivative model rather than embark on a clean-sheet design. Two 21-in. barrel plugs, one ahead and one aft of the wing root, were added to the 7X fuselage. The modification makes room for two additional windows on each side of the fuselage and adds about 3.5 ft. to cabin length. The stretch also makes room for a longer belly fairing with a more conformal tank that increases fuel capacity by about 2,500 lb. Internal modifications to the wing tanks add another 460 lb., increasing total fuel capacity by 2,960 lb. compared to that in the Falcon 7X.

G650

Gulfstream turned up the heat in the large-cabin business aircraft competition with its new G650 flagship, the largest, fastest, farthest-ranging—and at $64.5-million per copy—most expensive executive jet in the company's history. The aircraft cruises at nearly 30 kt. faster than the current generation of large-cabin business jets and its 7,000-nm range exceeds that of the G550, the previous distance leader, by 250 nm.

Pilatus PC-24

The much-anticipated Pilatus PC-24 might well be named the big Swiss surprise. Many people confuse it for a turbofan-powered variant of the PC-12. That would put it in the light jet class of the Cessna Citation CJ4 or Embraer Phenom 300, a market segment already overcrowded.

But it is actually a midsize jet with a slightly larger cross-section than a Citation XLS+. Admittedly, it has 7 in. less headroom in the center of the cabin; however, that is because it has a continuous flat floor rather than an 8-in. dropped aisle. The main seating area is 2.7 ft. longer than in the XLS+, affording comfortable seating for six people in the standard executive interior. With 500 cu. ft. of cabin volume, interior size alone puts the PC-24 into a midsize jet class that’s sparsely populated, now that the Gulfstream G150, Hawker 900XP and most of the midsize Citations no longer are in production.

G650

Being able to cruise at Mach 0.80 may have been the benchmark in the 20th century, but it seems slow by 21st century standards. Even long-haul airliners now can cruise at Mach 0.85. Bombardier indeed routinely quotes Mach 0.82 to 0.85 as the normal cruise speed for its current production Global series business jets.

The G650 now sets a new standard with its Mach 0.90 high-speed cruise and 6,000-nm range. Slow down to Mach 0.85 and it leads the ultra-long-range class with 7,000-nm range. Assuming standard day conditions, the aircraft can depart a 4,000-ft. runway and fly eight passengers 4,000 nm in just over 8 hr.

Falcon 7X

Dassault’s Falcon 7X was the first purpose-built business aircraft with a digital flight control system, a technology intended to ease pilot workload, provide flight envelope protection and enable designers to reduce drag and improve fuel efficiency.

Design of the system capitalizes on Dassault’s three-plus decades of building Mach 2-class fighters with fly-by-wire (FBW) flight controls. The company believes its military aircraft design experience gave it FBW design capabilities for the Falcon 7X that are not available to other civil aircraft manufacturers.

HondaJet HA-420

Michimasa Fujino, founding president and CEO of Honda Aircraft Company, Inc. (HACI) is understandably proud of the new HondaJet. He has personally guided its progress from initial conception to a fully developed model and certified aircraft, fighting through at least five years of delays in the process.

This is the culmination of his 30-year dream of building the world’s most advanced light jet, one that would be the highest flying, fastest cruising and most economical, one that would offer passengers the most cabin volume, the quietest interior and the smoothest ride.

Cirrus SF50 Vision Jet

Cirrus Aircraft’s SF50 Vision Jet makes no pretense of being a competitor in a light-jet niche already dominated by twin-turbofan aircraft from Embraer, Honda and Textron. Instead, it is the first of a new class of “personal” jets that bridges the gap between piston and turbine aircraft.

When the aircraft was launched in 2006, Cirrus predicted it would be the “lowest, slowest and least expensive” jet on the market. The manufacturer has succeeded in spades. Its base price of under $2 million makes the SF50 the lowest-cost turbofan on the market. And its performance is proportionate.

Let's go flying. Here's a look back at some of our most popular business jet pilot reports.