The past financial crisis in 2008 led to an aftermath with airlines retiring hundreds of aircraft per year, and with it the availability of used serviceable material (USM) exploding. This offered airlines cheap alternatives to expensive purchases of new parts or repairs.

In the years since, aviation has experienced such strong growth that mature aircraft have remained in service longer than predicted, resulting in a significant reduction in retirements, part-outs and, ultimately, short supply of used parts. Air traffic demand outpaced supply.

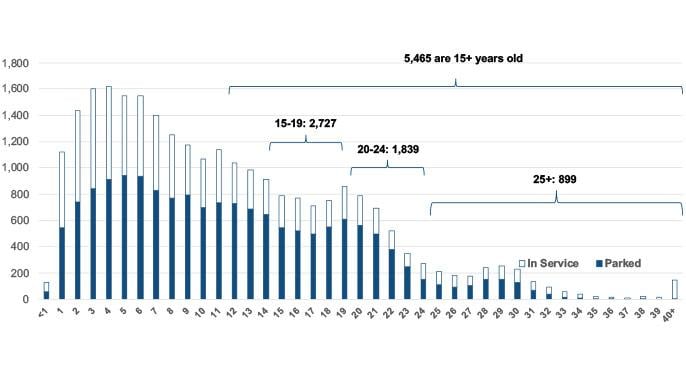

However, it has long been predicted that the roughly 2,000 aircraft delivered during the production peak in the late 1990s (now 20-24 years old) would ultimately reach the state of retirement.

COVID-19 has now accentuated this retirements wave by bringing air travel to nearly a halt with a recovery expected to be years from now. Of the 16,000 aircraft that are currently parked, far from all will return to service. The resulting retirements wave will be larger than what was projected only a few months ago.

How will this impact the timing and availability of USM and what will the impact be on the MRO market?

Paradoxically, this crisis may have bought OEMs some time to adapt their strategies, as AeroDynamic Advisory believes there will be 2-3 years before the wave of USM hits the market.

In this analysis, a few concepts play important roles in how airlines and lessors choose to proceed:

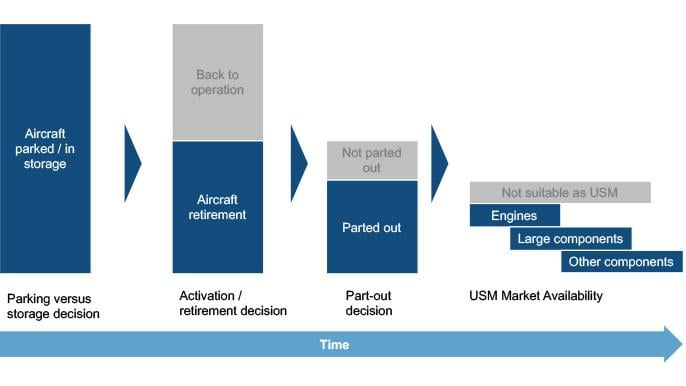

- Parking of aircraft: A condition that enables quick resumption of operations. Time period: up to six months. Requires a number of recurring maintenance actions so the aircraft remains in a “ready for flight” condition. Engines available to be “borrowed” for use on another aircraft—a practice called green time management, mostly for intra-fleet use to offset shop visits. Beyond this, airlines cannot easily bring aircraft back in operation if having removed more aircraft parts.

- Storage: Preservation of parked aircraft that are unlikely to return into service in the short-term. Typical period: Up to two years. Reduced maintenance schedule combined with preservation activities such as sealing and greasing. Engines as well as some high-value components (e.g. avionics, APUs, landing gear can be removed and used for green time on other aircraft.

- Retirement: The decision to decommission an aircraft and no longer keep it registered as airworthy. Aircraft can stay retired for years while waiting for a buyer; typically a company selling used parts.

- Dismantling/Part-out (“teardown”): The process to disassemble an aircraft, including uninstalling parts, removing fluids and tearing apart the structures. The parts that can be resold are packaged and put in a warehouse, available to be purchased. Parts from dismantled aircraft become USM.

- Used Serviceable Material (USM): Used parts or material, from parted-out aircraft or from airline inventories, that are available for use. Parts need to undergo inspection and sometimes maintenance activity to be certified as airworthy.

Although COVID-19 has led to an enormous surplus of aircraft, the actual wave of USM parts will not hit the market straight away—likely not until 2022-23. Here are the key reasons:

Part-outs won’t be conducted until maintenance demand recovers.

Demand for engine/component MRO will likely remain very low in 2020, with a small uptick in 2021 and real growth beyond that. The reasons are the slow growth expected in air travel demand combined with airlines’ use of cash conservation methods such as green time management and burning of their parts inventories.

Investment in part-out activities won’t happen if the monetary value is unclear. The potential oversupply may put enormous pressure on prices. For example, will the old rule of a typical aircraft scrap value of $10 million really hold in these conditions?

When demand returns, there may also be bottlenecks in the part-out industry that prevent all material from reaching the market. For example, will there be adequate part-out capacity available?

The airline sector will take some time before making retirement decision.

With the shape of traffic recovery yet being unclear, many airlines are holding off on significant fleet decisions. So far in 2020, airlines have announced intentions to retire/return some 700 aircraft; equivalent to roughly 3% of the fleet. The complete lack of demand for aircraft means selling isn’t a viable option for the moment.

Ultimately, keeping aircraft parked or stored carries an upkeep cost, and airlines/lessors will need to decide whether to bring these aircraft back into operation or retiring them. AeroDynamic Advisory expects as many as 4,000 aircraft retirements to be announced over the next three years.

There is a time lag from an aircraft part-out to the parts actually becoming available in the market.

In total, there can be a lag of 12-18+ months between a part-out and 90% of the parts being sold on the market.

Engines are the most valuable portion of an aircraft and will typically be turned first and generate the highest value for the seller. Large components such as APUs, landing gear, navigation and high value avionics, thrust reversers, and wheels and brakes are the next categories to be sold. Other components become available later, with the expensive runners being sold first.

In conclusion, the wave of USM from thousands of retired and torn down aircraft is on its way to reach the aftermarket. However, there will be some delay to this, given the market uncertainty, low demand and the economics of part-outs.

This means the challenges for OEMs and MRO providers will vary over time.

In the near-term, many are in survival mode due to the huge drop in demand. OEMs need to adapt to both 40% lower production rates and 60-70% lower aftermarket demand from air transport. Most MROs do not have other business segments to compensate because they have air transport as their only revenue source.

Short- to medium-term, aftermarket demand will be impacted by airlines’ use of green time management, thereby not growing in the same rate as air traffic. Aftermarket demand is delayed for some time—but not cancelled.

Long-term, the significant availability of USM will shape the purchasing behavior for airlines, to whom cost will be very important. In response, suppliers must develop or refine their aftermarket propositions. The COVID-19 crisis may have bought OEMs some time by pushing demand to a later point, but OEMs will need to be very flexible when demand picks up. It has been a difficult market for OEMs to address—the opportunity is on the buy side and in a world of excess it will be difficult even for experienced traders to find out what to invest in, and at what price.