Gallery: How Regulators and OEMs are Addressing Aircraft Nacelle Safety

Sean Broderick July 07, 2021

Improving nacelle designs to reduce engine-failure risks

Credit: Sean Broderick/AWST

Minimizing the risk of air transport engine failures has been a focus for decades—work that has paid off. The failure of an engine designed after the first generation of late 1960s high-bypass turbofans has never resulted in what regulators define as a “catastrophic” event involving multiple fatalities or loss of an aircraft. Most of the risk mitigation has focused on uncontained failures, defined by the FAA (Advisory Circular AC 33.5) as incidents in which fragments are released through the engine structure. The reason: debris exiting through the engine’s sides presents the highest risk to the cabin and flight-control surfaces, which puts passengers, fuel and critical controls in danger. But a recent series of engine failures underscores that even when debris is technically contained, risks can be high. As a result, industry is re-examining certification requirements and moving to correct model-specific risks on in-service aircraft.

Minimizing the risk of air transport engine failures has been a focus for decades—work that has paid off. The failure of an engine designed after the first generation of late 1960s high-bypass turbofans has never resulted in what regulators define as a “catastrophic” event involving multiple fatalities or loss of an aircraft. Most of the risk mitigation has focused on uncontained failures, defined by the FAA (Advisory Circular AC 33.5) as incidents in which fragments are released through the engine structure. The reason: debris exiting through the engine’s sides presents the highest risk to the cabin and flight-control surfaces, which puts passengers, fuel and critical controls in danger. But a recent series of engine failures underscores that even when debris is technically contained, risks can be high. As a result, industry is re-examining certification requirements and moving to correct model-specific risks on in-service aircraft.

In-service events raise concerns

Credit: NTSB (Southwest Flight 1380 investigation)

The shift in how engine failures are scrutinized stems primarily from four in-service events (Source: AWST). Two of them involve CFM56-7B-powered Southwest Airlines 737-700s—Flight 3472 near Pensacola in August 2016 and Flight 1380 near Philadelphia in April 2018. Both met the National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB) definition of an accident, and the second resulted in a passenger fatality. NTSB issued final reports on both accidents in 2020. The two others involved Pratt & Whitney PW4077-powered United Airlines Boeing 777-200s—Flight 1175 en route to Honolulu in February 2018 and Flight 328 near Denver in February 2021. The NTSB issued its final report on Flight 1175 in 2020 and is still investigating Flight 328.

The shift in how engine failures are scrutinized stems primarily from four in-service events (Source: AWST). Two of them involve CFM56-7B-powered Southwest Airlines 737-700s—Flight 3472 near Pensacola in August 2016 and Flight 1380 near Philadelphia in April 2018. Both met the National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB) definition of an accident, and the second resulted in a passenger fatality. NTSB issued final reports on both accidents in 2020. The two others involved Pratt & Whitney PW4077-powered United Airlines Boeing 777-200s—Flight 1175 en route to Honolulu in February 2018 and Flight 328 near Denver in February 2021. The NTSB issued its final report on Flight 1175 in 2020 and is still investigating Flight 328.

Common factors; blurred line between contained and uncontained failures

Credit: NTSB (United Flight 328 investigation)

All four events share several common factors. In each case, an engine/airframe combination certified more than two decades ago suffered an engine failure triggered by a fractured fan blade (Source: AWST). In both 777 incidents and Southwest Flight 1380, the engine met its certification requirements for contained fan-blade-out (FBO) events. Fragments were not ejected through the engine’s containment ring or case toward the airframe or wings. The NTSB classified Southwest Flight 3472 as an uncontained failure. While the final report discusses internal engine damage—including containment ring damage—and debris exiting both the inlet and exhaust, it does not discuss debris being ejected through the engine structure.

All four events share several common factors. In each case, an engine/airframe combination certified more than two decades ago suffered an engine failure triggered by a fractured fan blade (Source: AWST). In both 777 incidents and Southwest Flight 1380, the engine met its certification requirements for contained fan-blade-out (FBO) events. Fragments were not ejected through the engine’s containment ring or case toward the airframe or wings. The NTSB classified Southwest Flight 3472 as an uncontained failure. While the final report discusses internal engine damage—including containment ring damage—and debris exiting both the inlet and exhaust, it does not discuss debris being ejected through the engine structure.

Even contained failures can be high-risk events

Credit: NTSB (United Flight 328 investigation)

In all four events, the aircraft landed safely, thanks to what worked—the airframe and engine designs, underlying certification requirements and the pilots’ skills. Work on the root causes—fan blade fractures that pointed to the need for revamped inspection protocols—began right away (Source: Aviation Daily/AWIN). But airframe damage, parts being shed from around the engine and the Southwest Flight 1380 passenger fatality suggest unacceptably high risks remain. In all four cases, damage caused by blade fragments hitting sections of the engine’s nacelle, or outer covering, triggered a chain of events that caused large pieces of structure, including parts of engine inlets and fan cowls, to break away. All four aircraft suffered fuselage damage. During the Flight 1380 event, debris struck one of the 737’s windows and dislodged it, causing a rapid decompression that led to the fatality.

In all four events, the aircraft landed safely, thanks to what worked—the airframe and engine designs, underlying certification requirements and the pilots’ skills. Work on the root causes—fan blade fractures that pointed to the need for revamped inspection protocols—began right away (Source: Aviation Daily/AWIN). But airframe damage, parts being shed from around the engine and the Southwest Flight 1380 passenger fatality suggest unacceptably high risks remain. In all four cases, damage caused by blade fragments hitting sections of the engine’s nacelle, or outer covering, triggered a chain of events that caused large pieces of structure, including parts of engine inlets and fan cowls, to break away. All four aircraft suffered fuselage damage. During the Flight 1380 event, debris struck one of the 737’s windows and dislodged it, causing a rapid decompression that led to the fatality.

Engine certification: test, test, test

Credit: CFM International

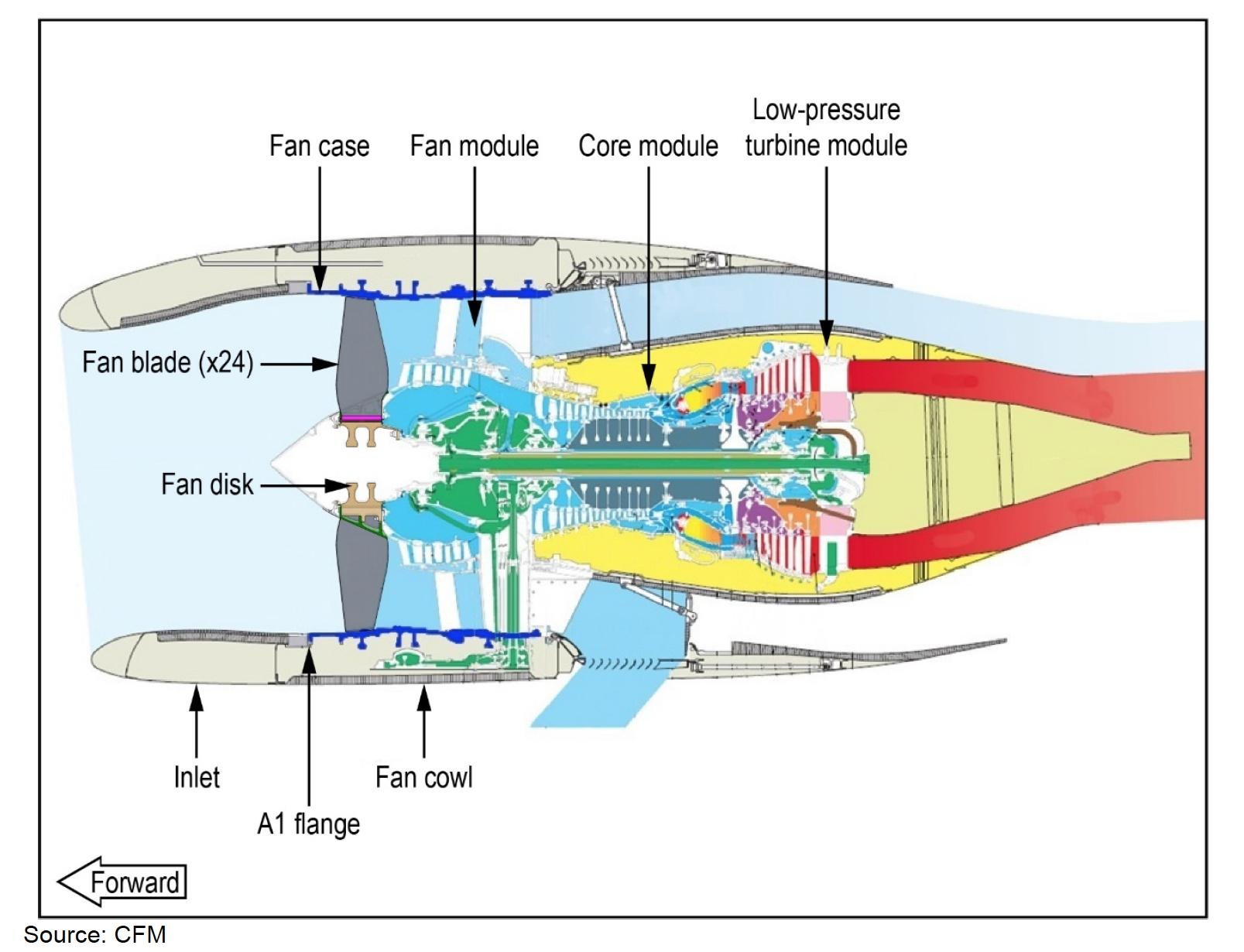

The Southwest investigations included a deep dive into aircraft and engine certification standards and how the two are integrated. Engine certification requirements include tests of different scenarios, such as bird strikes and water ingestion (pictured) that validate anticipated failure modes. For an FBO event, blades rigged with explosives are blown up to demonstrate how engines perform and whether fan cases contain all blade fragments. Cameras capture the tests, done on open-air stands. Results from a 1995 CFM56-7B certification test convinced Boeing and CFM to redesign the engine’s fan case and containment shield. The new design passed a subsequent test—one of 10 (eight rig tests, two FBO containment certification tests) the engine underwent on its way to approval.

The Southwest investigations included a deep dive into aircraft and engine certification standards and how the two are integrated. Engine certification requirements include tests of different scenarios, such as bird strikes and water ingestion (pictured) that validate anticipated failure modes. For an FBO event, blades rigged with explosives are blown up to demonstrate how engines perform and whether fan cases contain all blade fragments. Cameras capture the tests, done on open-air stands. Results from a 1995 CFM56-7B certification test convinced Boeing and CFM to redesign the engine’s fan case and containment shield. The new design passed a subsequent test—one of 10 (eight rig tests, two FBO containment certification tests) the engine underwent on its way to approval.

Aircraft nacelle certification: analysis rules

Credit: CFM via NTSB (Southwest Flight 1380 investigation)

Aircraft certification does not require similar testing of nacelles. Covering the engine during its tests would not allow cameras to capture needed information, and nacelle components, including the inlet and fan cowl, provide little additional protection. Instead, approval of the nacelle and related components leans heavily on analysis. Among the outcomes the analysis must support: a single, foreseeable failure such as an FBO event cannot lead to nacelle fragments breaking away and jeopardizing continued safe flight. During the Southwest 1380 investigation, experts from Boeing and CFM International testified that analysis methods have improved significantly since the 737 Next Generation was certified. Specifically, current modeling can better predict where blades will impact cowls, and what the ramifications will be (Source: Aviation Daily/AWIN).

Aircraft certification does not require similar testing of nacelles. Covering the engine during its tests would not allow cameras to capture needed information, and nacelle components, including the inlet and fan cowl, provide little additional protection. Instead, approval of the nacelle and related components leans heavily on analysis. Among the outcomes the analysis must support: a single, foreseeable failure such as an FBO event cannot lead to nacelle fragments breaking away and jeopardizing continued safe flight. During the Southwest 1380 investigation, experts from Boeing and CFM International testified that analysis methods have improved significantly since the 737 Next Generation was certified. Specifically, current modeling can better predict where blades will impact cowls, and what the ramifications will be (Source: Aviation Daily/AWIN).

Lessons learned leading to changes

Credit: Sean Broderick/AWST

The NTSB agreed. Among its recommendations to the FAA in its final report on Flight 1380: order Boeing to re-design its CFM56-7B nacelle. Boeing is close to releasing recommended modifications to the inlet, fan cowl and exhaust nozzle (Source: Aviation Daily/AWIN) and the FAA plans to mandate them—a move that will likely cascade into a global requirement as other regulators follow suit. Boeing is working on similar changes for at least some 777s. Bigger picture, the NTSB ordered FAA and other regulators to scrutinize certification requirements and analyze possible failure modes using the latest modeling. The agency should then ensure airframe and engine manufacturers are working collaboratively to incorporate lessons learned into their designs, taking into account design evolutions such as larger fan blades being incorporated into current-generation engines. This work is ongoing.

The NTSB agreed. Among its recommendations to the FAA in its final report on Flight 1380: order Boeing to re-design its CFM56-7B nacelle. Boeing is close to releasing recommended modifications to the inlet, fan cowl and exhaust nozzle (Source: Aviation Daily/AWIN) and the FAA plans to mandate them—a move that will likely cascade into a global requirement as other regulators follow suit. Boeing is working on similar changes for at least some 777s. Bigger picture, the NTSB ordered FAA and other regulators to scrutinize certification requirements and analyze possible failure modes using the latest modeling. The agency should then ensure airframe and engine manufacturers are working collaboratively to incorporate lessons learned into their designs, taking into account design evolutions such as larger fan blades being incorporated into current-generation engines. This work is ongoing.

A look at how recent engine failures have led to increased engine testing, analysis and nacelle modifications.