Our Favorite Scoops

May 06, 2016

1919: Orville Wright’s Call for Runways

Fifteen years after he and his brother Wilbur first took to the air at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, Orville Wright believed development of the aviation industry still had a long way to go. In a Viewpoint written for Aviation Week—then known as Aviation and Aeronautical Engineering—Wright called for “distinctly marked and carefully prepared landing places.” To make flying safe, those runways “should be spaced every 10-12 miles,” he wrote. Wright argued that while upkeep for a plane cost more than an automobile, it was “very much less than that of a yacht.” He also envisioned airplanes being used more for commercial purposes, noting that they could make the trip from his hometown of Dayton, Ohio, to Washington in just 3 hr. compared with 16 hr. for a rail trip. “The airplane has already been made abundantly safe for flight,” Wright wrote. “The problem before the engineer today is that of providing for safe landing.”

Read Orville Wright’s Viewpoint from Jan. 1, 1919, at: archive.aviationweek.com

1927: Love Letters With Mussolini

Benito Mussolini is remembered as the bombastic Italian leader and Nazi ally during World War II. Less known is that the fascist dictator was a more respected figure—and an aviation enthusiast—when he rose to power in the 1920s. In a fawning letter to Mussolini published in the April 4, 1927, edition of Aviation, the magazine’s founder and publisher, Lester D. Gardner, expressed “the deepest admiration from innumerable Americans who are interested in aeronautical problems. . . . You deserve the unstinted praise of every traveler for the creation of the Italian air lines and the splendid facilities you have made available.” Gardner also complimented Italy’s strong air defenses. Mussolini’s reply was published in the same issue. “I am well aware of the magazine Aviation, which you edit, is the champion in your country of the broadest and most rapid development of the wings of peace and war,” he wrote. Fifteen years later, the two countries would be at war.

Read the original article from April 4, 1927, at: archive.aviationweek.com

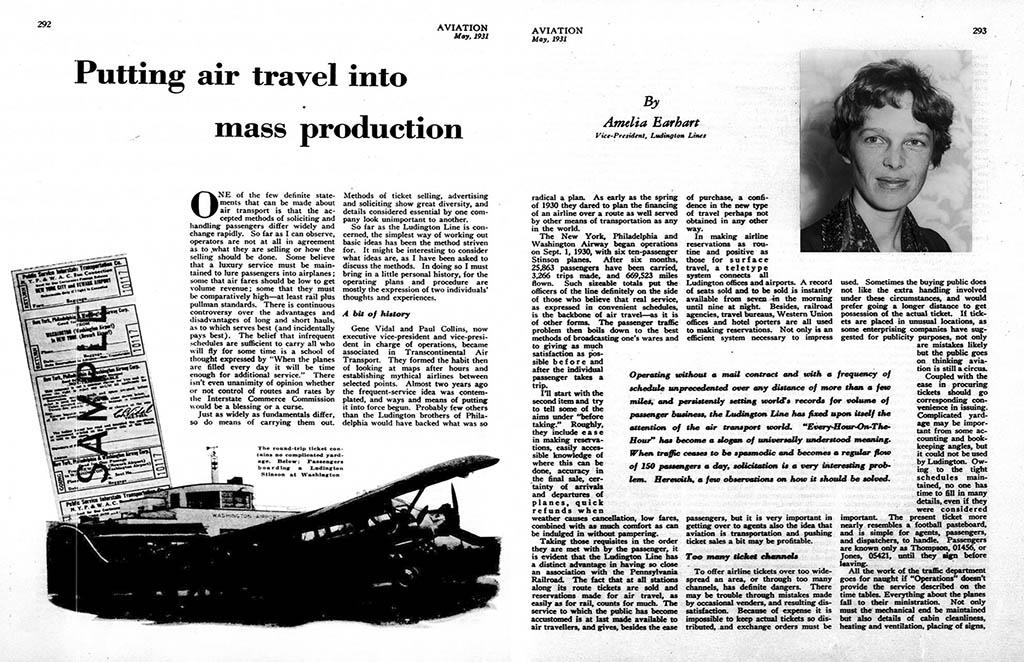

1931: How To Run an Airline, by Amelia Earhart

Six years before her 1937 disappearance over the Pacific Ocean during a flight around the world in her Lockheed Electra, aviation pioneer Amelia Earhart was vice president at Ludington Lines, an airline that shuttled passengers around the northeast U.S. in 10-seat Stinson aircraft. In a Viewpoint written for Aviation Week—then known as Aviation—she opined on “Putting Air Travel into Mass Production.” Some key elements: convenient schedules, “real service,” low fares, centralized ticketing, quick refunds for weather-related cancellations and “as much comfort as can be indulged without pampering.” The three-page piece delves into the need for cabin comfort, including clean windows and brushed carpets—along with some then-modern innovations. “Probably no single mechanical measure has meant more to the traffic department than heated airplanes throughout the winter,” Earhart wrote.

Read Earhart’s original Viewpoint in the May 1931 edition of Aviation at: archive.aviationweek.com

1947: Yeager Breaks the Sound Barrier

In late 1947, Aviation Week revealed that the fabled “sound barrier” had been broken by U.S. Air Force Capt. Charles “Chuck” Yeager in the Bell XS-1. The news was leaked to the magazine’s renowned engineering editor Robert McLarren, two months after the Oct. 14 flight over Muroc Dry Lake, California. It made instant headlines around the world. Described by McLarren as the Bell XS-1 (“S” for supersonic, a title later simplified to X-1), the fuselage’s shape closely resembled a 0.50-caliber bullet, the theory being that this was known to be a stable aerodynamic shape at sonic velocity. The rocket-powered vehicle also had straight, thin-but-strong wings, which McLarren identified as a significant factor given that swept wings were fast becoming the favored configuration for higher-speed designs. “Now the possibility exists that swept wings will not be required for supersonic aircraft, and a reevaluation of high-speed design characteristics of current projects is indicated.” Given the pioneering times, we can forgive McLarren for such speculation. It is also curious to see in the story that Yeager’s name is misspelled Yaeger. Was this a simple error, or perhaps deliberately done as part of efforts to protect Aviation Week’s source?

Read McLarren’s original story in the Dec. 22, 1947, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

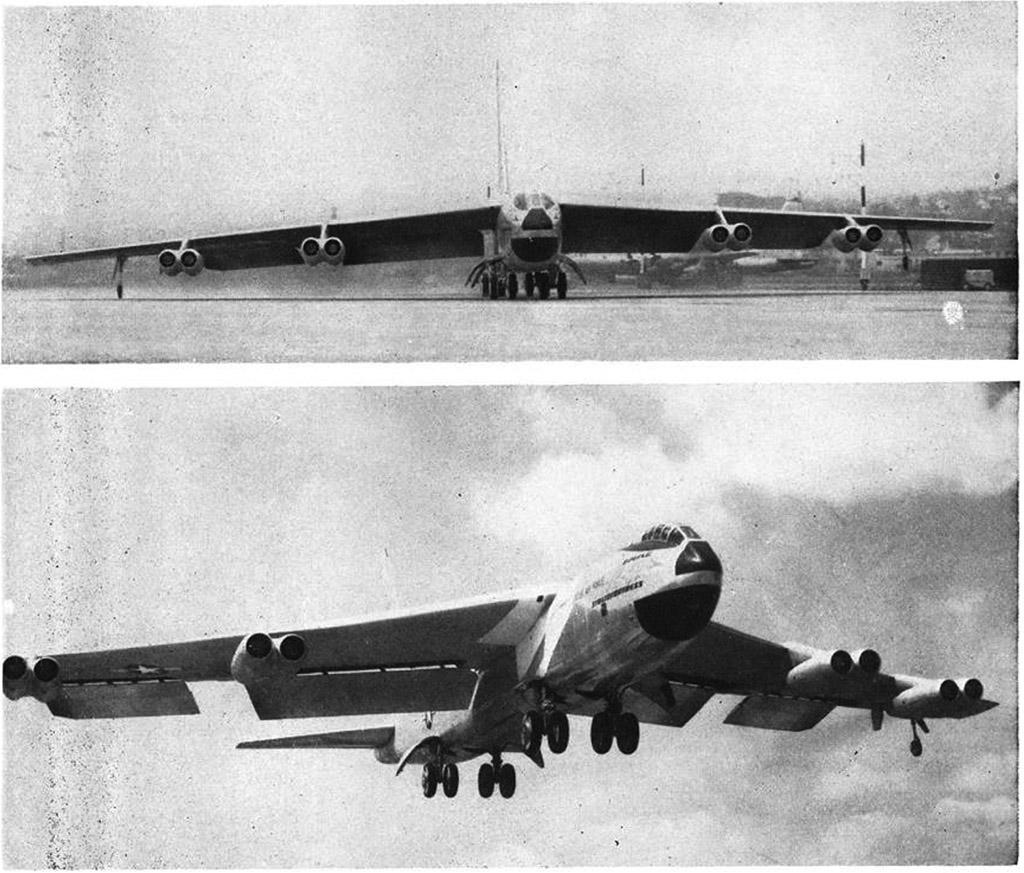

1952: Lifting the Veil on the B-52

In the summer of 1952, Aviation Week provided the first details on the new Boeing-built B-52 bomber. But the scoop came with a price tag: The magazine had to agree not to publish any data that was not cleared in advance by the U.S. Defense Department. In return, writer Alexander McSurely received an Air Force clearance to go to Seattle for an up-close inspection of the exterior of two B-52s, though he was not allowed inside the aircraft. McSurely’s article still contained plenty of details about the B-52 and its eight Pratt & Whitney J57 jet engines. He also wrote about the debate over whether the bomber would quickly be replaced by guided missiles. That would not prove to be the case. More than six decades later, there are still 77 B-52H bombers in service with the Air Force, according to data from the Aviation Week Intelligence Network.

Read McSurely’s original story on the B-52 in the Aug. 18, 1952, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

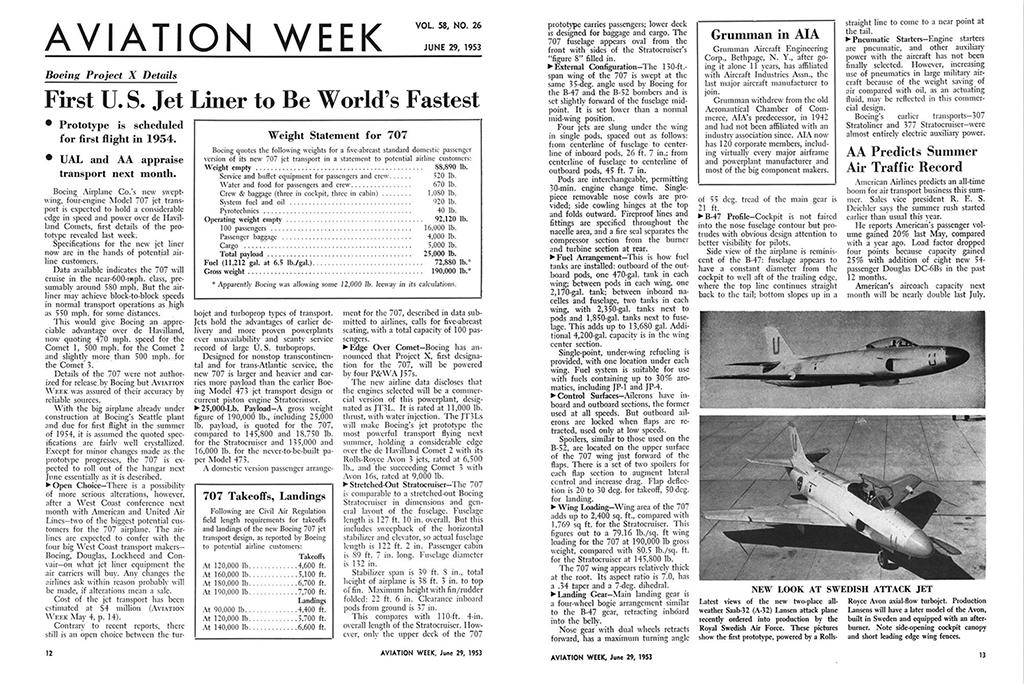

1953: Boeing’s 'Project X'

“First U.S. Jet Liner to Be World’s Fastest.” So read the Aviation Week headline from the summer of 1953, lifting the wraps on Boeing’s “Project X” to develop its first passenger jet, the 707. “Details of the 707 were not authorized for release by Boeing, but Aviation Week was assured of their accuracy by reliable sources,” said the article. Aviation Week noted that the 707 was expected to achieve a cruise speed of 580 mph, faster than the 500 mph for the de Havilland Comet 2 and Comet 3. The article’s prediction of a first flight the following year proved spot on. The first 707 prototype flew on July 15, 1954. The 707 entered service in 1958 with Pan American World Airways, but the competition Boeing faced was fierce. The Douglas DC-8 passenger jet and a revamped Comet were also hitting the market. The 707’s performance would be greatly improved with the introduction of Pratt & Whitney’s JT3D turbofan engines in 1961.

Read the original story in the June 29, 1953, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

1958: A Nuclear-Powered Soviet Bomber

Occasionally, one of Aviation Week’s scoops became an “oops.” That was the case in 1958, when the magazine “revealed” that the Soviet Union had been flight testing a nuclear-powered bomber near Moscow for six months. The account included a remarkable level of detail. “The new aircraft is powered by a combination of nuclear and conventional turbojet engines,” the article maintained. “Two direct air cycle nuclear powerplants are housed in 36-ft.-long nacelles slung on short pylons about midway out on each wing. These nuclear powerplants, with 6-ft.-diameter air intakes . . . produce about 70,000 lb. thrust each.” The report, which fueled concerns that the Soviets were pulling ahead of the U.S. in nuclear propulsion, would prove to be an elaborate hoax. Both Soviet and U.S. research into nuclear-powered aircraft wound down in the 1960s as ICBMs rendered the concept obsolete. Today, despite vast improvements in reactor technology, fission-based nuclear propulsion cycles remain heavy, complex and inefficient.

Read an account of the 1958 Soviet nuclear bomber hoax and link to the original article from Dec. 1, 1958 at:

archive.aviationweek.com

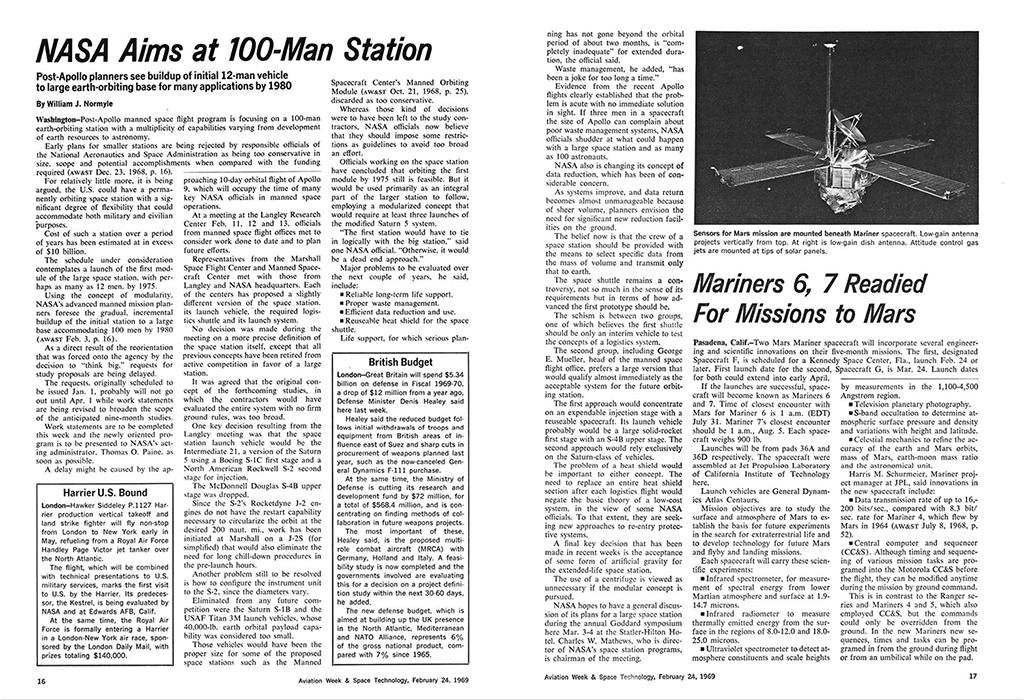

1969: A 100-Person Space Station

Over the decades, many of Aviation Week’s scoops involved ambitious proposals that never came to be. Five months before Apollo 11 astronauts set foot on the Moon, NASA was already pursuing some grandiose plans for the post-Apollo era. In a February 1969 article, space technology editor William J. Normyle revealed that officials for NASA’s manned space program were drawing up plans for a massive space station that could accommodate 100 astronauts and be used for both civil and military purposes. Under the grand proposal, the station would be built in a modular fashion, starting in 1975 with completion in 1980. One challenge: waste management. “If three men in a spacecraft the size of Apollo can complain about poor waste management systems, NASA officials shudder at what could happen with a large space station,” Normyle dryly opined. Alas, it would take another three decades before the much smaller—but still large—International Space Station would start to be assembled and begin operations.

Read Normyle’s original story in the Feb. 24, 1969, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

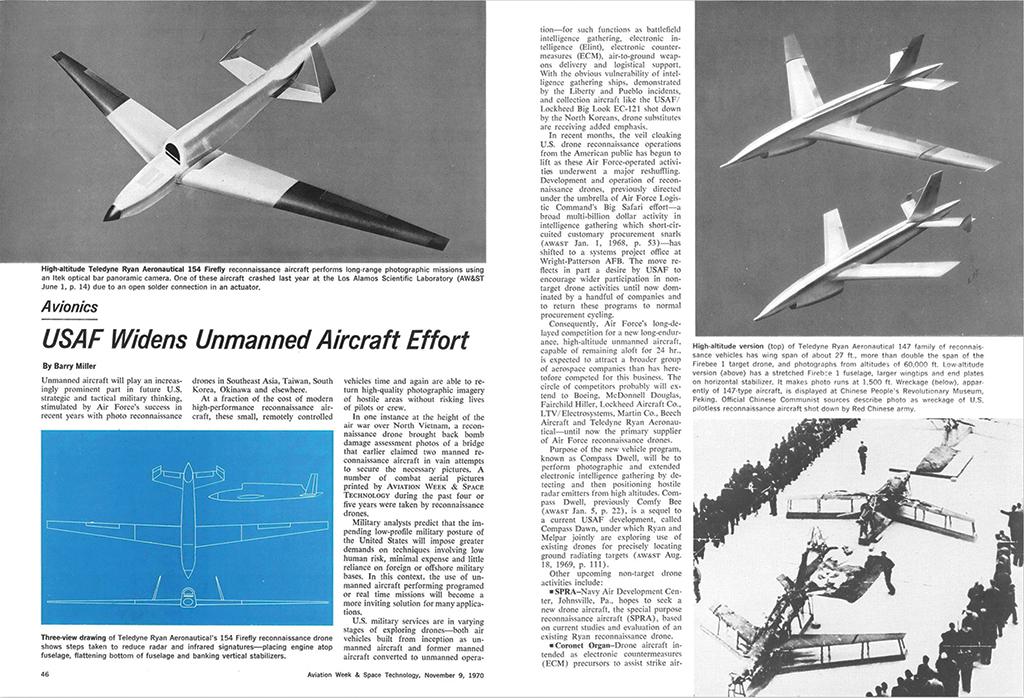

Unmanned Aircraft, Circa 1970

In November 1970, Los Angeles Bureau Chief Barry Miller provided a detailed account of the U.S. Air Force’s efforts to expand its use of unmanned aircraft. “These small, remotely controlled vehicles time and time again are able to turn in high-quality photographic images of hostile areas without risking lives of pilots or crew,” Miller wrote. The Vietnam War-era article led off with drawings of the secret Teledyne Ryan Aeronautical 154 Firefly, designed to fly at more than 80,000 ft. It was powered by a specially developed engine, the General Electric J97. A few years before anyone spoke of stealth, the article noted that designers of the 154 had ”taken steps to reduce radar and infrared signatures—placing engine atop fuselage, flattening bottom of fuselage and banking vertical stabilizers.” In the end, the program appeared to be ahead of its time. It was mothballed in 1973, after 28 aircraft had been built, and it would be decades before unmanned aircraft played the prominent role envisioned in Miller’s article.

Read an account of early Air Force unmanned efforts and link to Miller’s original story at: aviationweek.com/100

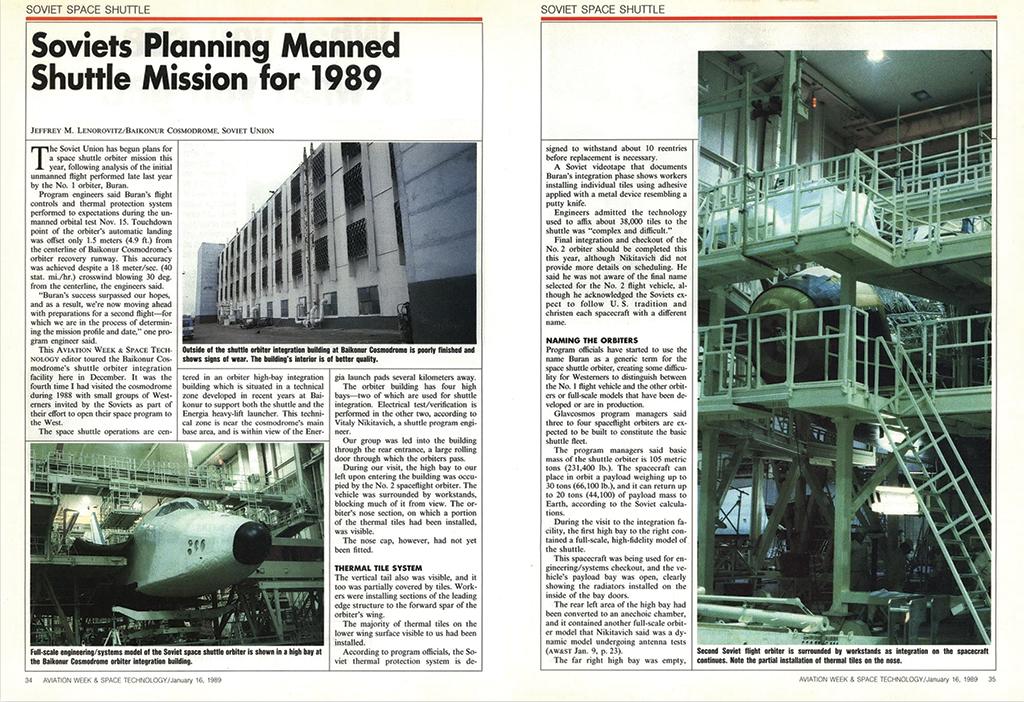

1978: A Soviet Space Shuttle

Three years before the U.S. flew its first space shuttle mission, Aviation Week revealed that the Soviet Union was developing its own reusable spaceplane. An article by space technology editor Craig Covault said that the Russians had developed a Delta-winged vehicle that “has design characteristics similar to the U.S. orbiter . . . . This significant new Soviet manned program indicates the USSR has the technology in hand to tackle the major engineering challenges involved in building reusable manned spacecraft.” The article included a fuzzy concept image of what the Soviet test shuttle might look like. A decade later, shortly after the Buran flight vehicle made an unmanned orbital test flight, European editor Jeffrey Lenorovitz was given a tour of the Soviet shuttle integration facility and wrote of plans for a manned mission in 1989. But it was not to be. The Buran never flew again, and the program was terminated following the breakup of the

Soviet Union.

Read the March 20, 1978, and Jan. 16, 1989, articles on the Soviet shuttle program at: archive.aviationweek.com

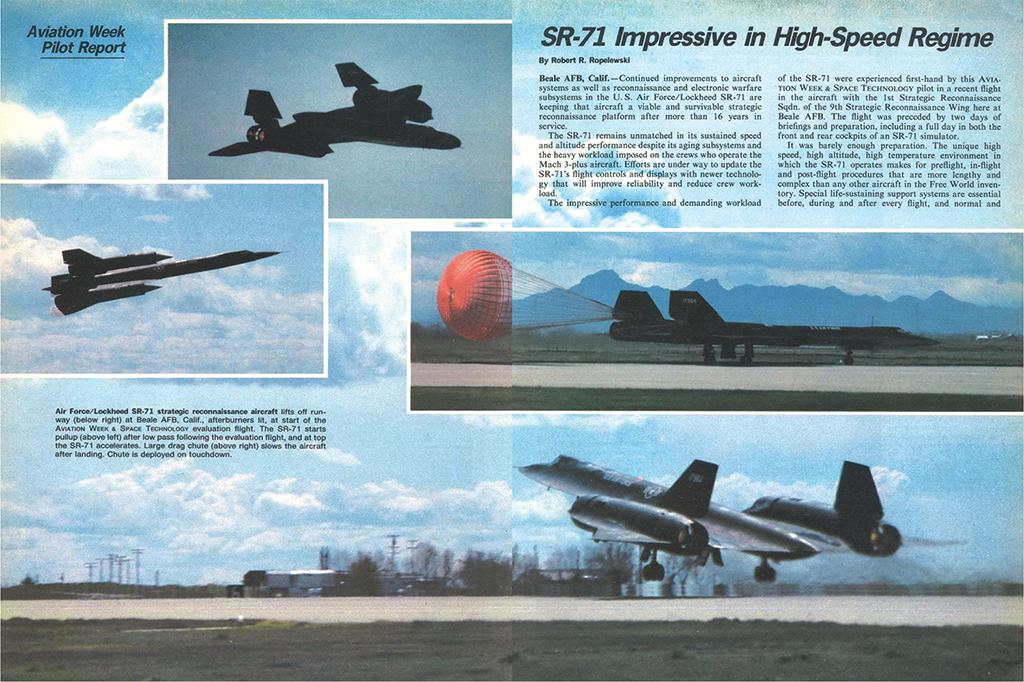

1981: Flying the SR-71

In 1981, Aviation Week Los Angeles Bureau Chief Robert Ropelewski became the first journalist to fly the now-iconic Lockheed SR-71 reconnaissance jet. The 1.4-hr. flight from Beale AFB in California covered 1,800 mi. and was preceded by two days of briefings and preparations. Ropelewski wrote that “special life-sustaining support systems are essential before, during and after every flight. . . . Despite this, the SR-71 makes flight at Mach 3 and 80,000 ft. seem easy.” From that height he was easily able to see the curvature of the Earth, and his blow-by-blow account of the flight and accompanying photos filled nine pages in the magazine. But Ropelewski noted that, from a pilot’s point of view, the Blackbird was a “glaring paradox in terms of the late 1950s/early 1960s technology used in the cockpit to manage a system whose performance is still considered advanced in the early 1980s.” The SR-71 was retired by the U.S. Air Force in 1990, brought back into service and finally retired for good after final missions for NASA in 1999. Ropelewski had died two years earlier of a heart attack. He was 54.

Read the full SR-71 pilot report in the May 18, 1981, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

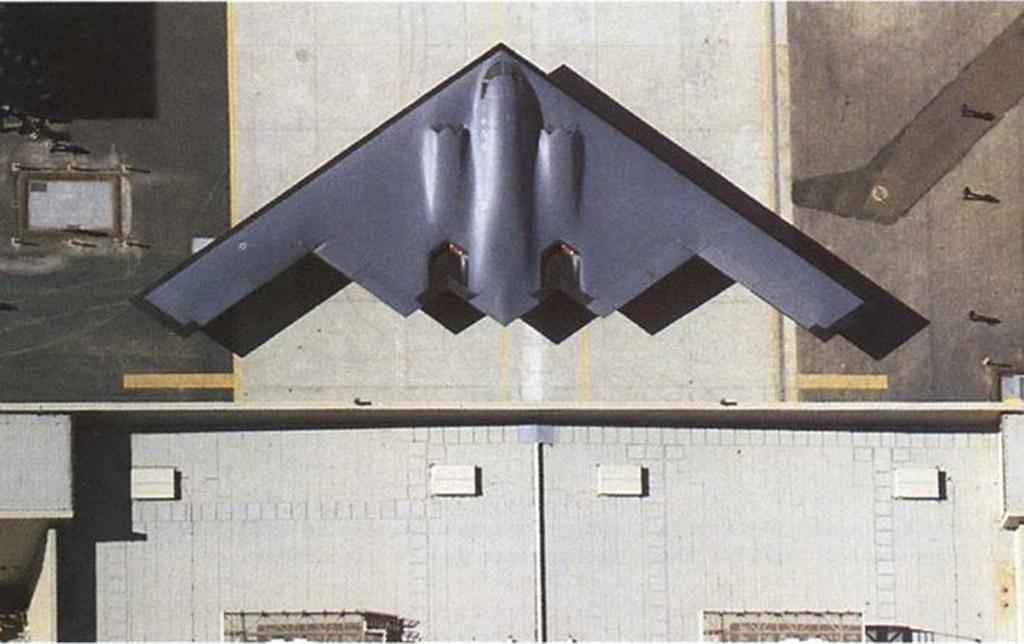

1988: 'Where’s Dornheim?'

The rollout of the Northrop B-2 bomber in November 1988 was a milestone in military aviation. Fourteen years after the word “stealth” crept into print, the public had yet to see a stealthy aircraft. But U.S. Air Force officials were determined to conduct the historic event on their terms. Reporters at the Palmdale, California, site were confined to bleachers, providing a limited view of the B-2 and hiding details about its exhaust system. Guard dogs patrolled the perimeter around the aircraft. As the media gathered in a highly secure holding area, someone asked, “Where’s Dornheim?” Unimpressed by the officials’ restrictions, Michael A. Dornheim, Aviation Week’s senior engineering editor, decided to go over their heads—literally. Anyone looking up during the ceremony could spot a Cessna 172 circling overhead, piloted by Dornheim and carrying photographer Bill Hartenstein. Aviation Week came away with an exclusive photo that revealed that every edge of the aircraft was parallel to one or the other of the long leading edges of the aircraft. It was a pivotal moment in public understanding of stealth. Dornheim was killed in a car crash in 2006, but the legend of how he outsmarted the Air Force in a rented Cessna lives on.

Read more about the B-2 rollout and link to Dornheim’s original article at: Aviationweek.com/blog/1988-b-2-stealth-unveiled

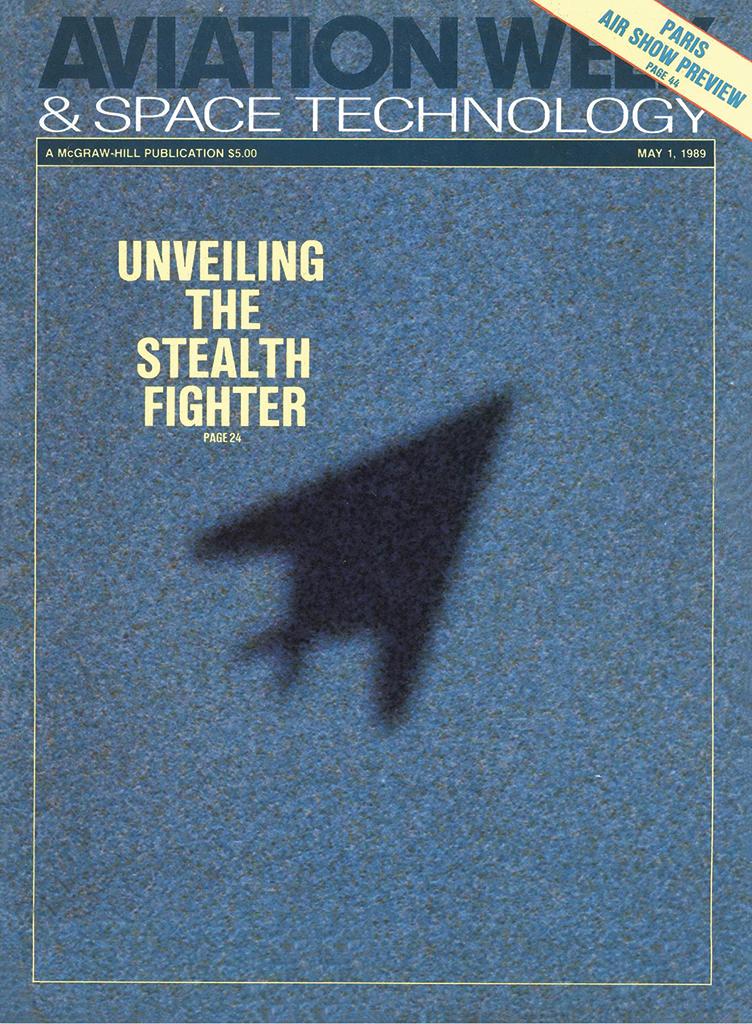

1989: Unveiling the Stealth Fighter

The U.S. Air Force acknowledged the existence of the F-117A, a stealthy attack aircraft that was designated a fighter, despite its lack of air-to-air weapons, in

November 1988, five years after the Lockheed-built aircraft became operational. But officials released only a murky “photograph” that provided scant details on the F-117A’s unique design characteristics. Five months later, Aviation Week obtained and published a telephoto image of an F-117A flying near Edwards AFB, California, accompanied by detailed analyses of the aircraft’s characteristics and training flights by engineering editors Michael A. Dornheim and William B. Scott. “The highly swept F-117A wing has an aspect ratio of about 1.9, based on its gross area, which probably penalizes the aircraft’s aerodynamic efficiency,” Dornheim wrote. “But it also may reduce radar cross-section when viewed from some aspects.” The telephoto image was so grainy that some editors thought it unusable. But they were overruled by Editor-in-Chief Donald E. Fink. “He said, ‘That’s the first photo’” of the F-117A, Scott recalls. “We’re going with it.” And onto the cover it went.

View the original F-117 cover and articles from May 1, 1989, at: archive.aviationweek.com

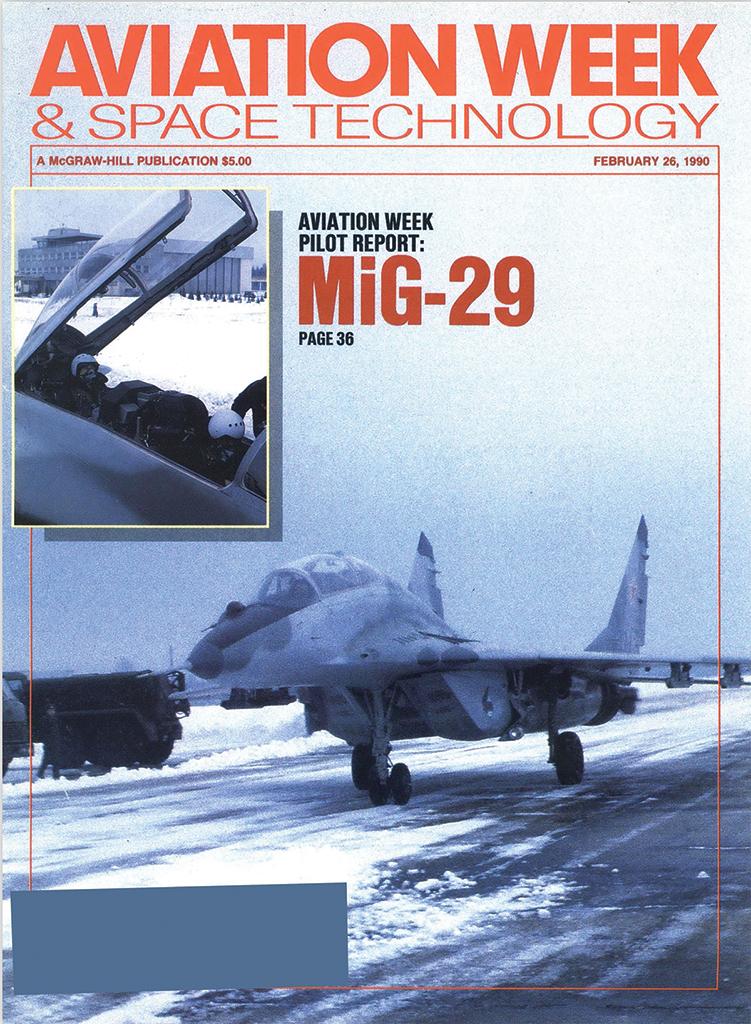

1990: Reporting from the Cockpit—of Soviet Fighters

In January 1990, just two months after the opening of the Berlin Wall, Editor-in-Chief David M. North became the first journalist to fly the Soviet Union’s Mikoyan MiG-29 fighter. In a pilot report from Kubinka Air Base near Moscow, North noted that the MiG-29’s controls were more akin to the McDonnell Douglas A-4s he had flown in the 1960s than the F/A-18s he had flown more recently. Still, he found the MiG-29 to be “very agile,” rugged and designed to be maintained by personnel with limited training. A few months later, at the Farnborough Airshow, he became the first American pilot to fly the Sukhoi Su-27 fighter, performing 150-deg./sec rolls over the English countryside. “I was flying with a Russian pilot who spoke little English,” North recalls. “The saving grace was that he was the most experienced Su-27 pilot flying.”

Read the story behind David M. North’s flights of the MiG-29 and Su-27 and link to his original pilot reports at: aviationweek.com/100

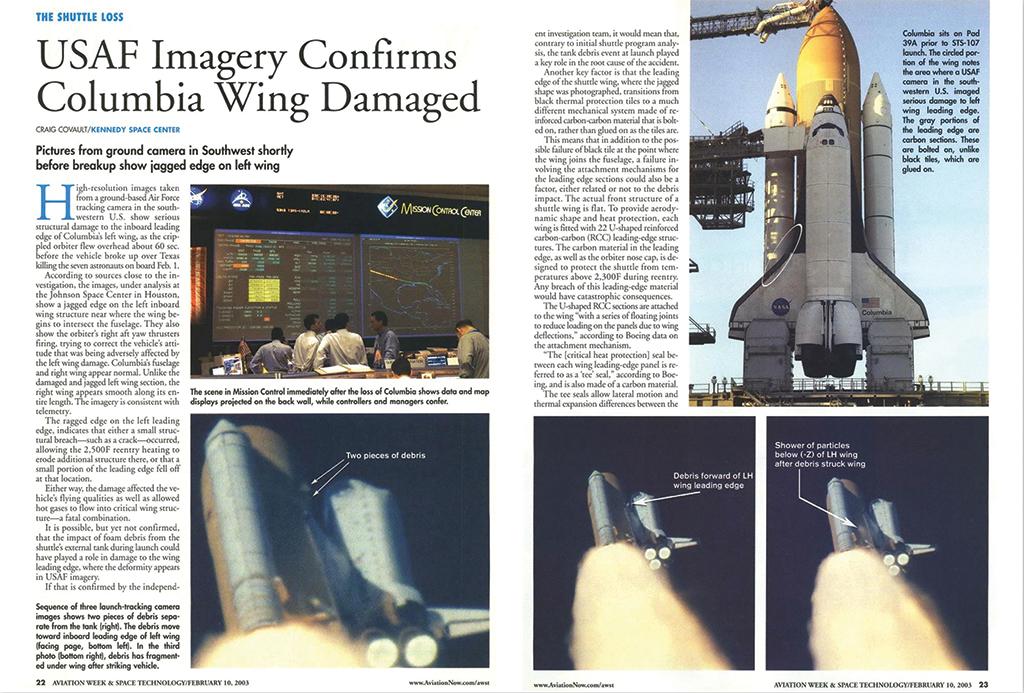

2003: The Columbia Tragedy

There was plenty of media coverage of the Feb. 1, 2003, loss of space shuttle Columbia, which broke apart over Texas as it reentered the atmosphere, killing its crew of seven. But Aviation Week set itself apart with its in-depth, team analysis of the accident. Exclusive interviews with Program Manager Ron Dittemore and Flight Director Leroy Cain provided key points in the breakup. The magazine’s initial coverage described how high-resolution imagery of the shuttle taken by a U.S. Air Force tracking camera revealed damage to the inboard leading edge of Columbia’s left wing, which was later determined to have been caused by a piece of foam insulation that broke off of the shuttle’s propellant tank during launch. The magazine also published an exclusive photo from inside Mission Control immediately after the loss of the shuttle. The coverage by space editors Craig Covault and Frank Morring, Jr., and engineering editor Michael A. Dornheim, among others, went on to win a Jesse H. Neal Award, the business press equivalent of the Pulitzer Prize.

See Aviation Week’s coverage of the Columbia accident from February 2003 at: archive.aviationweek.com

2007: Revealing China’s Satellite Killer

Aviation Week’s revelation that China had tested an anti-satellite (Asat) weapon, destroying one of its own aging weather satellites orbiting 537 mi. above Earth, created quite a sensation. And it made China a pariah among spacefaring nations for instantly and drastically increasing the mass of dangerous space junk in orbit. Longtime space technology editor Craig Covault broke the story on AviationWeek.com on Jan. 17, 2007, six days after the test, and it was quickly confirmed by the White House. In a detailed analysis in the magazine that followed, Covault noted that China’s successful test of an Asat weapon “means that the country has mastered key space sensor, tracking and other technologies for advancing military space operations. China also can now use ‘space control’ as a policy weapon.” The story opened a global debate on Asats—and especially Chinese Asats—that continues to this day.

Read the original story in the Jan. 22, 2007, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

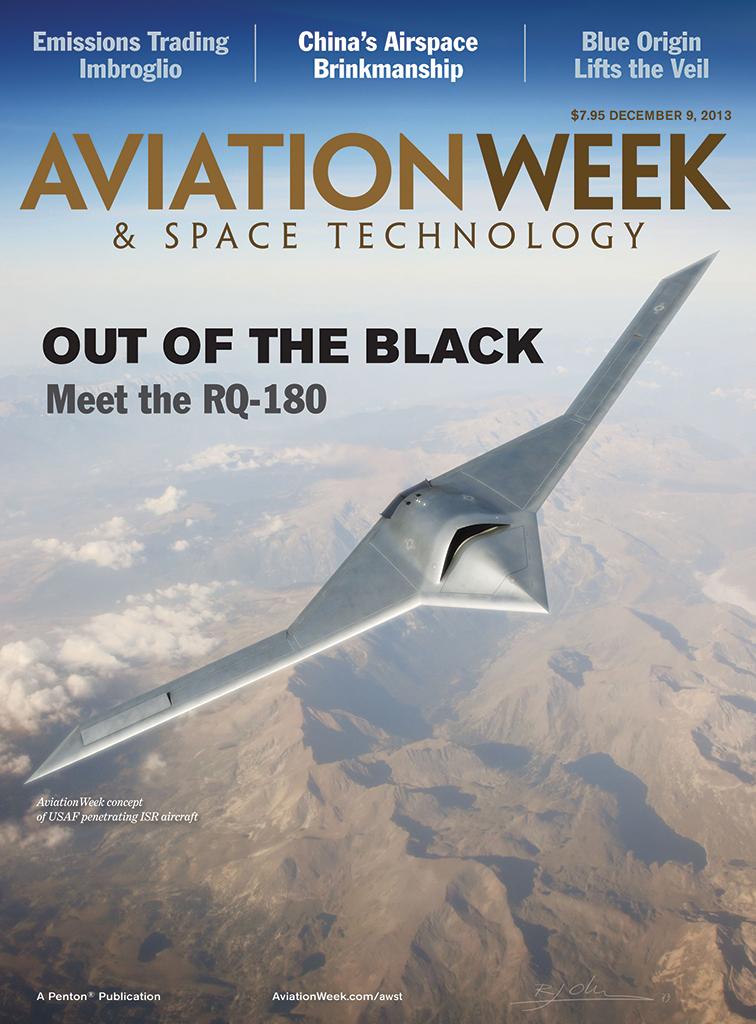

2013: Unmasking the RQ-180

In late 2013, defense editors Amy Butler and Bill Sweetman revealed the existence of the RQ-180, a large, classified unmanned aircraft built by Northrop Grumman and designed to combine advances in stealth and aerodynamics. Their revelation, based on multiple sources and months of reporting, explained how the RQ-180 was part of a U.S. Air Force effort to shift its intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance focus away from “permissive” environments such as Iraq and Afghanistan to environments that require penetrating the airspace of adversaries with advanced defenses. They also identified the RQ-180 as “a stepping-stone to the development of the Air Force’s Long-Range Strike Bomber,” which was subsequently awarded to Northrop Grumman, in October 2015, and is now designated the B-21. Aviation Week collaborated with artist Ronnie Olsthoorn to create a concept image of the RQ-180, which appeared on the magazine’s cover and online. The revelation on AviationWeek.com caused a huge spike in traffic to the site.

Read the original article unmasking the RQ-180 in the Dec. 9, 2013, edition of Aviation Week at: archive.aviationweek.com

When the U.S. Air Force tried to limit the view of reporters during the rollout of the stealthy B-2 bomber, an enterprising Aviation Week editor rented a Cessna 172 and took photographs from above. From its unveiling of the B-52 bomber and Boeing 707 jet to the classified RQ-180 unmanned aircraft and China’s anti-satellite weapon, Aviation Week has produced some legendary scoops over the past 100 years. Here are some of our favorites.

See more content from the 100th anniversary issue of Aviation Week & Space Technology