The formation of a UK Space Command, following in the footsteps of allies such as France and the U.S., was the headline pronouncement of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s plans to spend an extra £24 billion ($32 billion) on defense over the next four years.

But apart from the claim of being able to launch a rocket from 2022, the plans are thin on detail; a formal strategy to underpin the UK’s space plans is still to be published.

- UK has lobbied at UN on responsible behavior in space

- RAF has developed Aurora system to bolster space awareness

However, niche capabilities, projection of soft power and aligning closely with allies appear to be at the heart of the strategy.

Even with billions of pounds more available for the armed forces, the UK will lack the resources of space superpowers such as the U.S., Russia or, increasingly, China. The British government is pushing to secure a position in space, in part to help boost the national economy post-Brexit but also to make sure it has a voice in the way space is governed and the domain is available to use for defense and security needs.

A National Space Strategy is currently being developed by the UK Ministry of Defense and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and is guided by a newly established National Space Council led by several senior cabinet ministers. The strategy will underpin those plans: It will define the assets and capabilities the UK will need to invest in and how the UK will align with allies, and it will inform how the UK can support a growing space industry in the future with regulations and generate the necessary skills base.

The strategy is likely to call for a cross-government approach to space, so that numerous government departments will be able to benefit from services. This could even lead to the launch of dual-use, government-operated Earth-observation satellites that could perform either environmental monitoring over the UK or military reconnaissance elsewhere.

The strategy is separate from the UK’s spaceflight regulations, recently the subject of consultation, and from the Space Bill, which are enabling commercial satellite launches from UK spaceports.

Uncertainty remains about when the space strategy will finally see the light of day. It had been linked with the upcoming but long delayed Integrated Review of the UK’s defense and foreign policy. Defense officials now expect the document to be published early in 2021.

“Our strategy needs to set our vision for the UK’s place in the future, what commercial markets we want to prioritize, the discoveries we are best placed to meet and the assets needed to provide public services,” said Claire Barcham, strategy director at the UK Space Agency, speaking at the UK Defense Space Conference on Nov. 17.

“The UK wants to be seen as a force for good,” said Samantha Job, director for defense and international security and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, speaking at the same event.

“Our soft power will depend on our flourishing civil space sector,” Job said. “That gives us the authority to be in the conversation.”

The UK has already been making its voice heard on space matters. Earlier this month, it successfully secured a United Nations resolution successfully reinvigorating stalled discussions on the responsible behavior in space, aiming to prevent what the U.N. describes as a “celestial arms race.”

Some 150 countries voted in favor of the resolution, and 12 rejected it, while others, notably Russia, actively lobbied against it. The aim is to generate a baseline for space behavior so that space activities do not inadvertently lead to conflict back on Earth. Job said: “The aim is to reduce the risk of misunderstanding and miscalculation,” with the resolution potentially leading to a legally binding instrument that would call on countries to communicate if they decided to move a satellite close to that of another country.

It could also lead to a reduction in the testing of anti-satellite weapons that generate debris that can damage communication or navigation satellites on which the global economy has a growing dependence.

The resolution aligns with the UK’s plans to grow its space domain awareness capabilities, with the aim of being able to “unequivocally attribute activity,” Air Vice Marshall Harvey Smyth, the UK defense ministry’s newly appointed director for space, said at the event.

“We are witnessing countries like Russia push the boundaries of acceptable norms and behaviors,” Smyth said. “We don’t accept this activity in any other domain, so why should space be any different?”

Earlier this year, Smyth joined U.S. Space Force colleagues in condemning Russia for a series of anti-satellite tests, involving satellites Cosmos 2542 and 2543.

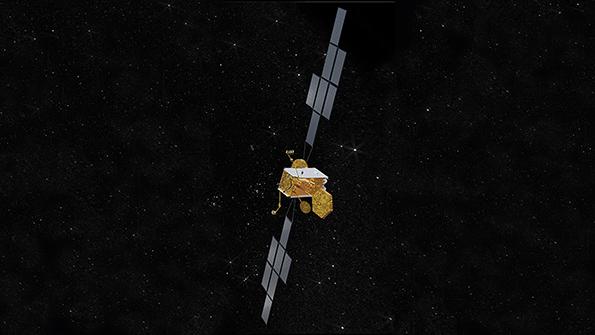

As part of its efforts to improve space awareness, the UK has invested in a system called Aurora, a new operating system for the UK’s Space Domain Awareness and Space Command and Control developed jointly by the UK Royal Air Force (RAF), which leads the UK’s space domain efforts, and the UK Space Agency. Aurora will “fuse analysis of space events enabling the UK to make a leading-edge contribution to international space domain awareness,” Air Chief Marshal Sir Mike Wigston, the RAF’s chief, told the conference.

Smyth said that with the UK’s limited budget, it was important to take a “smart and sophisticated approach” to the strategy.

“You can spend a lot of money in space, and you can bet on the wrong horse,” Smyth said. The UK will instead lean on specializations in secure and resilient satellite communications, software-defined capabilities, diverse waveforms and novel sensor technologies.

“We are trying to get to a point where we have got capabilities that the UK can develop and no other country can,” Smyth said. “That keeps us there, right at the top of the pedestal.”

Comments

As usual the MOD and RAF are late to the party; despite having manned Fylingdales since 1964, their space knowledge is abysmal, and it is only in recent years they have scrambled to learn. If you go back to that era, the UK had terrific tracking capability in radar and optical work, world beating orbit analysis at Farnborough (space department were the first to point out Skylab would not survive solar maximum, and the US chewed them out, until they ran the numbers and the blood ran from their face) and at RRS Ditton Park. The UK Gov got rid of all of it and the knowledge dispersed, symptomatic of UK scientific policy - if it does not make a profit in X years, then can it. The whole episode now seems to be someone's favourite pet project and to have us puffed up, because all others are introducing 'space commands'. We should have been doing this 30 years ago, but no one has vision, nor listens in Whitehall. Plus ca change...