New Horizons: Tantalizing Preview Of Coming Attractions

July 29, 2015

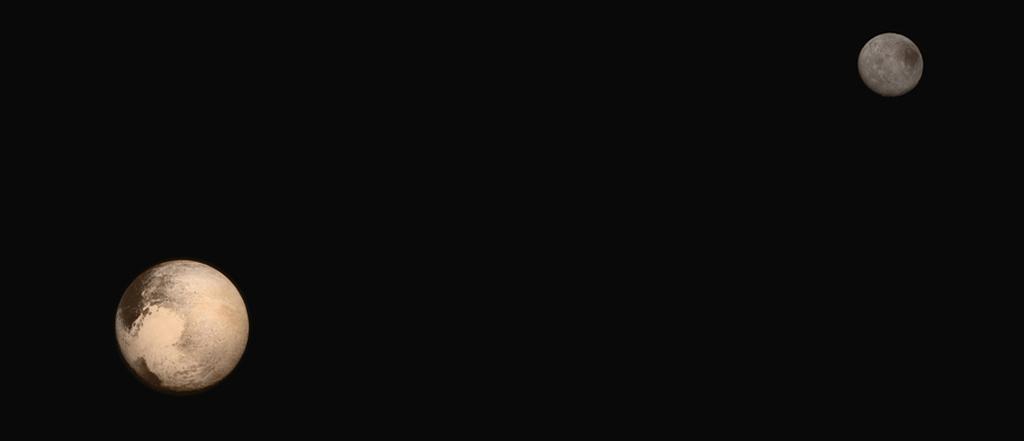

This composite of images collected by the Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (Lorri) and lower-resolution color data provided by the Ralph instrument—named for the 1950s sitcom character Ralph Kramden—reveals Pluto and its large moon Charon at a range of 150,000 mi., within a day of the July 14 closest approach of 7,750 mi. Pluto is smaller than Earth’s moon, and Charon is a little more than half Pluto’s size. Like the Earth-Moon system, scientists believe the two were formed in an ancient collision with a third body. Together Pluto and Charon are a “binary dwarf,” orbiting a point that lies between them in space.

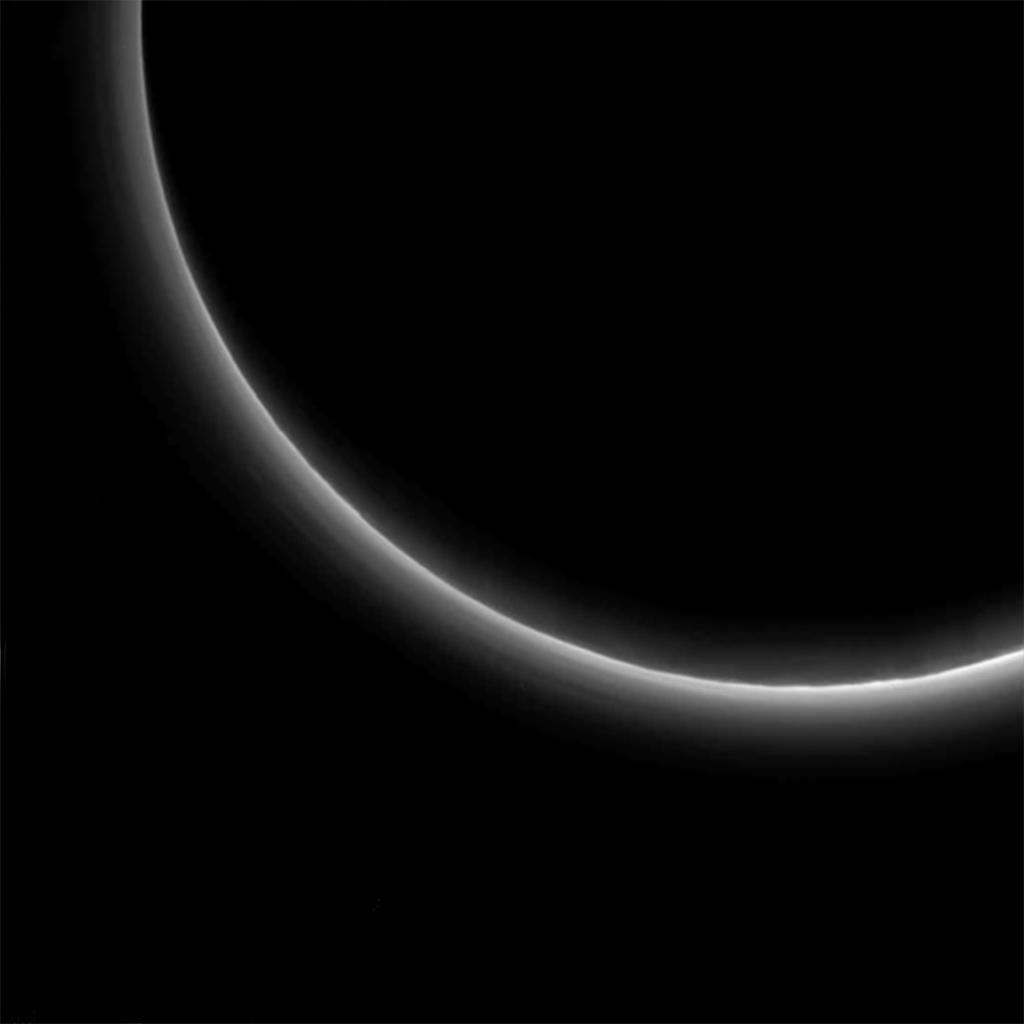

Seven hours after it passed through the Pluto system, New Horizons swiveled around to capture this view of the dwarf planet’s hazy atmosphere with its Lorri telescope/camera. The image confirms earlier suspicions that Pluto is surrounded by a haze of complex hydrocarbons, including ethylene and acetylene, formed by the interaction of ultraviolet light from the Sun and methane in the upper atmosphere. Analysis of the early data suggests there are two layers of haze, at 30 and 50 mi. altitude. The atmosphere itself is much deeper than previously suspected, rising about 100 mi. above the surface. Charon, by contrast, did not register an atmosphere in the first datasets, although scientists say information still stored on the spacecraft could reveal a tenuous atmosphere surrounding the big moon.

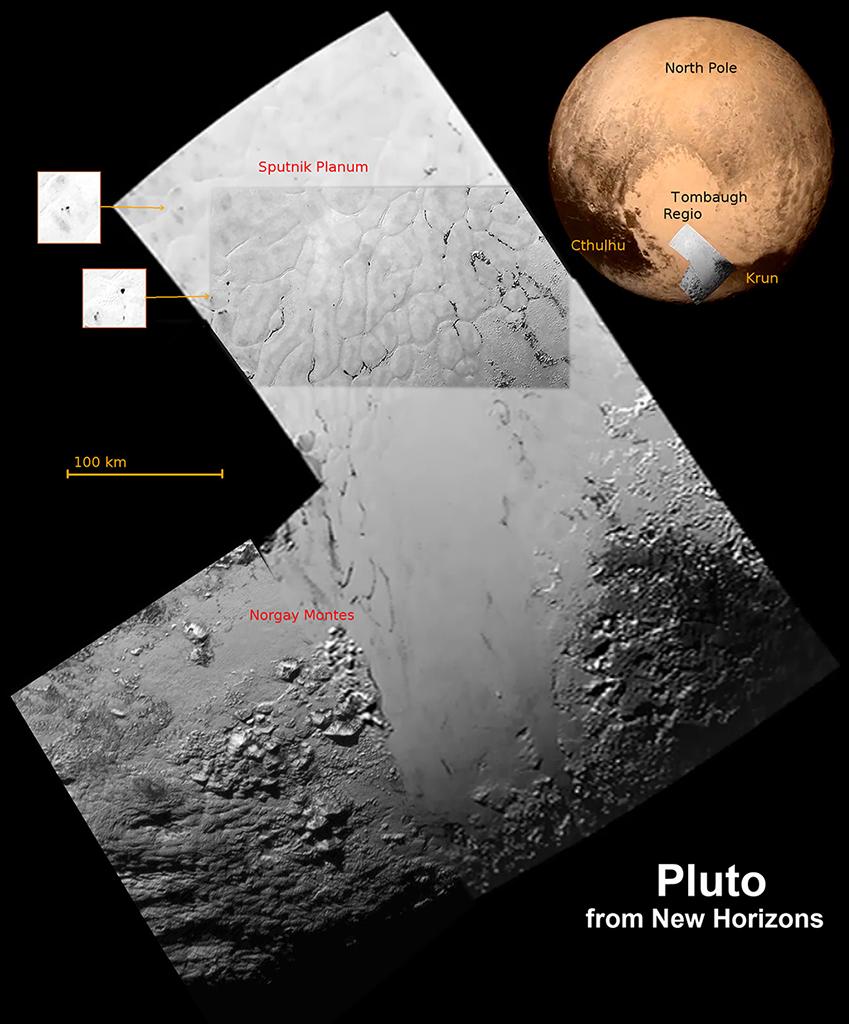

The first data down from New Horizons contained only a few segments of high-resolution panchromatic surface imagery collected by Lorri, superimposed in this mosaic against the lower-resolution approach image of the side of Pluto that was facing the spacecraft during the flyby. Science-team members informally named some of the features in the first downloads, as well as the heart-shaped plain “Tombaugh Regio” named for Clyde Tombaugh, the astronomer who discovered Pluto in 1930. The dark features highlighted at upper left appear to be wind streaks on the frozen-nitrogen surface, possibly associated with vents ejecting material from the interior. The mountains, named for Tenzing Norgay, the Nepalese Sherpa who accompanied Edmund Hillary to the summit of Mount Everest, are believed to be made of water ice, and to be comparable in size to the Rocky Mountains on Earth.

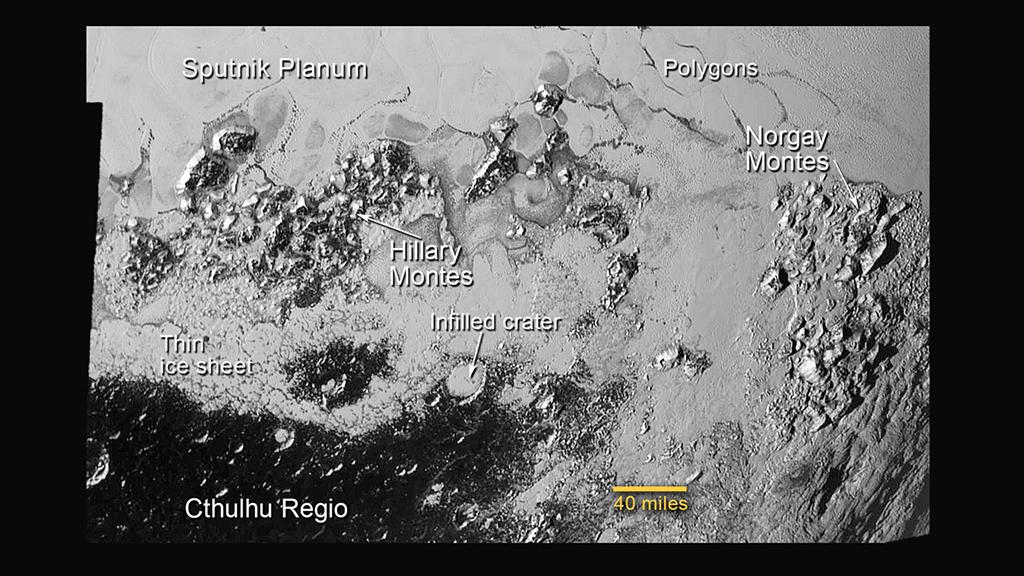

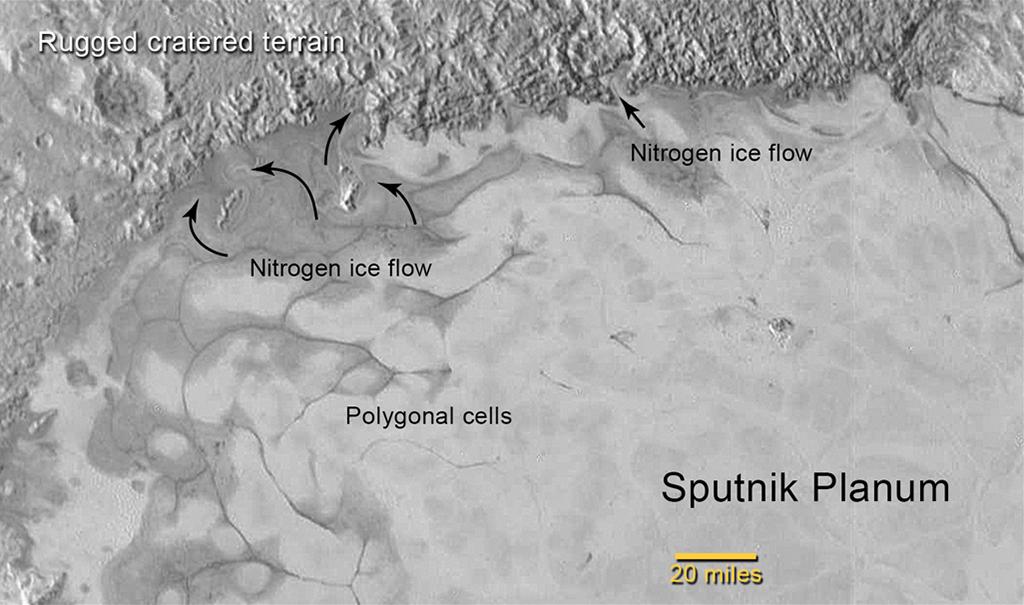

Scientists are surprised at the complexity revealed so far in high-resolution images of Pluto’s surface. At the southern end of the plain named for the Soviet satellite that ushered in the Space Age, the vaguely polygonal nitrogen-ice structures give way to two ranges of water-ice mountains—Hillary and Norgay—and dark-cratered terrain to the south of a thinner sheet of frozen nitrogen. Spectroscopy has revealed the fresh, uncratered icy plains to be a source of carbon monoxide on Pluto, and New Horizons scientists say the polygons may be evidence of upwelling from the warmer interior.

At the temperature on Pluto’s surface—less than 40K—water ice is too hard and brittle to flow. But frozen nitrogen, methane and carbon monoxide—the ices that make up Sputnik Planum—are “geologically soft and malleable,” says William McKinnon of Washington University, a co-investigator on the New Horizons mission. “Even at Pluto conditions . . . they will flow in the same way that glaciers do on the Earth.” In this image McKinnon has marked the flows of nitrogen glaciers, leaving the uncratered surface that is probably only a few tens of millions years old and heading into older terrain pocked with craters from ancient impacts. The spacecraft’s flash memory holds information that will allow the science team to create stereo images and calculate relative elevations across the dwarf planet’s surface.

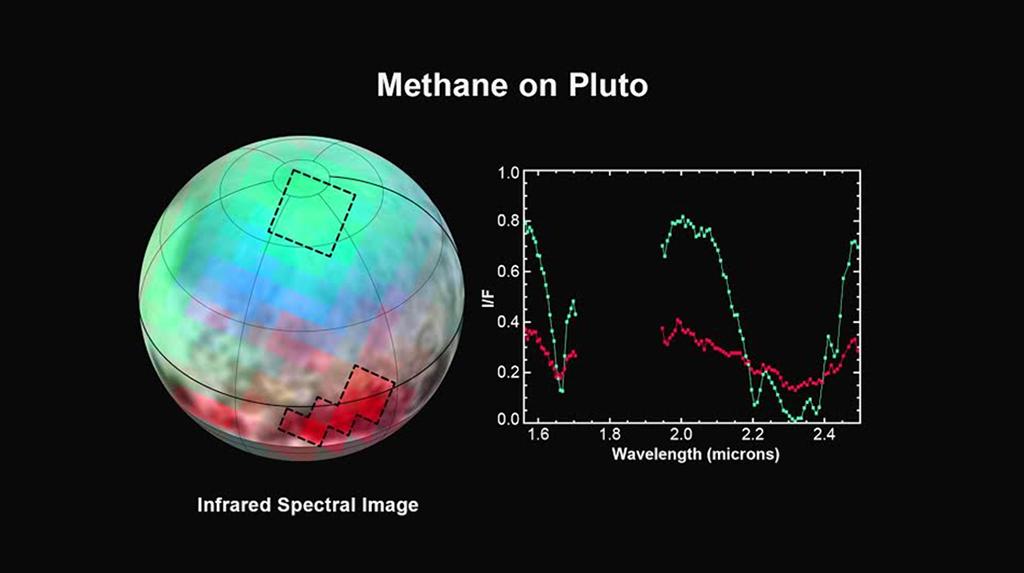

The Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array in the Ralph instrument has already delivered some details on the makeup of methane ice on Pluto’s surface. In this depiction of the data, blue represents medium absorption of light by methane ice; green is a channel where methane ice does not absorb light, and red represents regions where methane ice strongly absorbs light. From the data, scientists conclude that at the north pole a thick slab of transparent nitrogen ice dilutes the methane, while in the equatorial region where the red channel—wavelength 2.30-2.33 micrometers—either is less nitrogen-diluted, or has a different texture than the polar ice.

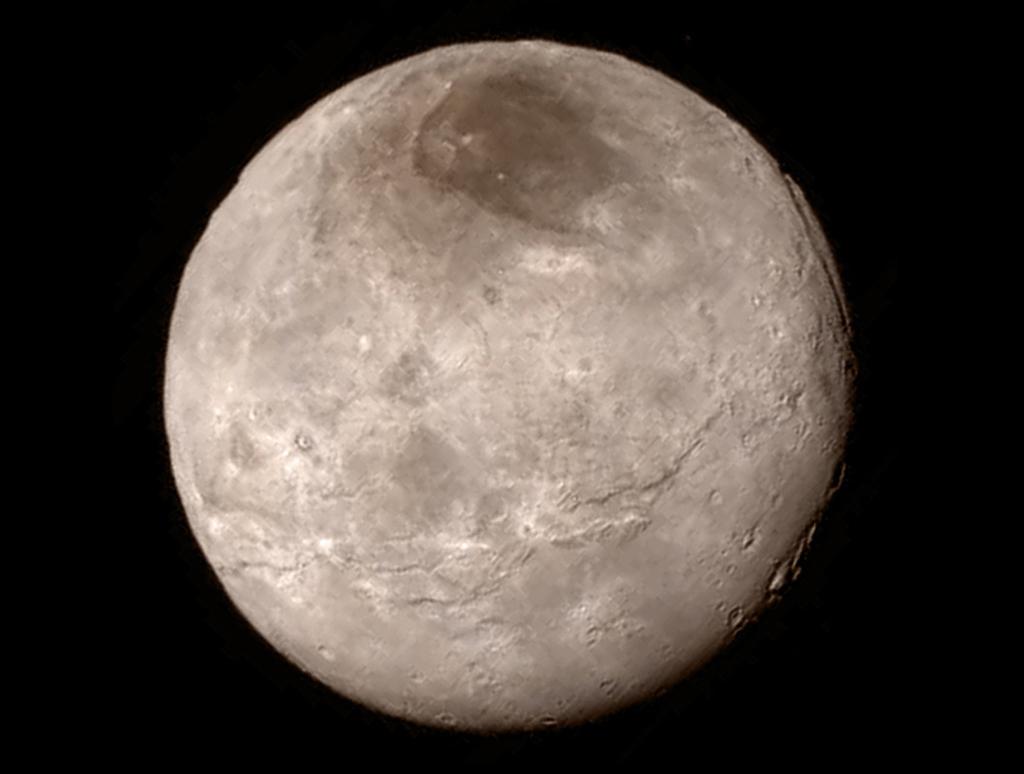

New Horizons’ Lorri instrument produced this image of Charon late on the day before closest approach, at a range of 289,000 mi. It shows unexpected signs that Pluto’s largest moon may still be geologically active. The deep valley near the horizon in the 2 o'clock position on the disk is a canyon 4-6 mi. deep, and a line of cliffs ranges 600 mi. across the surface facing the spacecraft. Scientists say that could mean internal processes are fracturing the surface. The relative absence of craters also is evidence that the surface has been reshaped since Charon was formed, possibly as a splinter from Pluto in a collision with a third body.

New Horizons imaged two of the four tiny moons orbiting Pluto beyond the orbit of Charon early on July 14. Nix, on the left, measures 26 X 22 mi., and in the color-enhanced image produced by the Ralph instrument has a distinct reddish spot on the side facing the spacecraft. Nix was about 102,000 mi. distant when the image was collected, at a resolution that shows features down to about 2 mi. across. The Lorri instrument imaged Hydra, the larger moon, at a range of 143,000 mi., producing a resolution of 0.7 mi./pixel, and allowing scientists to calculate its size at 34 X 25 mi. Two craters are visible on the right side of the irregular object, and the resolution is fine enough to distinguish a darker shade to its upper portion that suggests a different surface composition. Images of the two moons discovered with the Hubble Space Telescope in 2005—Styx and Kerberos—are expected to be transmitted by mid-October.

It will take until October-November 2016 for all of the data from the New Horizons flyby of Pluto to reach Earth, but first-look imagery and other information from the spacecraft indicate the dwarf planet and its moons will keep scientists busy for years trying to understand these strange new worlds.