A completed series of tests on the first Pratt & Whitney XA101 experimental turbofan comes as the manufacturer adapts to new support from U.S. Air Force leadership to replace the company’s F135 powerplants on the Lockheed Martin F-35A.

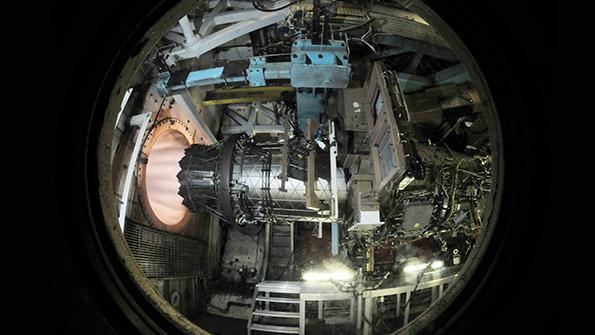

The XA101—Pratt’s entry in the competitive Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP)—delivered “amazing” results in the first series of ground testing completed in mid-September, says Matthew Bromberg, president of Pratt’s Military Engines unit. A second XA101 engine will enter ground testing next.

- Pressure for upgrade or replace F-35's propulsion system

- Growing needs for power and thermal management

“Now, we’re focused on the rest of the [AETP] program,” Bromberg says.

A series of ground testing will continue in 2022 for the Pratt engine and the rival GE Aviation XA100, but both manufacturers are positioning to win a potentially breakthrough propulsion upgrade program for the F-35A fleet.

Seventeen years after the first F135 engine entered testing, the Defense Department is weighing whether the time has come to embrace a new propulsion system for the single-engine fighter.

Although adaptive propulsion continues to be a candidate for a new design of a next-generation fighter, the Air Force also launched the AETP program in 2016 as a reengining option for the F-35. An adaptive engine inserts a new bypass flow duct, which can be opened in cruise flight to improve fuel efficiency and act as another source of cooling air for the electrical system.

As the XA100 and XA101 enter testing, pressure is growing to upgrade or replace the F-35’s propulsion system.

A planned series of electronic and sensor upgrades over the next five years is expected to exhaust the power and thermal management capacity of the fighter’s current engine. A National Defense Strategy focused on operations in the Pacific theater also adds demand to increase the F-35’s range. Meanwhile, a shortage of F135s caused by a lack of spares and a bottleneck at the repair depot has left dozens of F-35As grounded, prompting Air Force officials to reconsider the merits of competitive engine selection a decade after canceling the GE F136 alternate engine program.

For GE, the path forward is simple: Seek to replace the F135 engine on the F-35A fleet with the XA100, a new engine with a three-stream core that can modulate the bypass flow to increase fuel efficiency by up to 25%. GE has completed the first series of ground tests on both XA100 prototypes funded by AETP.

But the strategy for Pratt is more complicated. By embracing the F-35A reengining proposal, the company gains the chance to transition the XA101 adaptive engine into service. However, it also opens the door to losing the F135’s prized monopoly position on the largest fighter program in the world—if GE wins the contract.

Pratt officials also have developed the Engine Enhancement Package 25 (formerly known as Growth Options 1 and 2), which promises near-term upgrades to increase the thrust, fuel efficiency, power and thermal management capacity of the F135.

In the past, Pratt executives have downplayed the reengining option in favor of upgrading the F135. In addition to the billions of dollars needed to test and certify a new engine on the F-35, Bromberg has previously said that a reengining would create a mixed fleet, which adds the costs of duplicative infrastructure for production, maintenance and training. The three-stream engine design developed for AETP also is incompatible with the engine bay dimensions for the F-35B, the short-takeoff-and-vertical-landing version.

Until recently, Air Force officials have largely agreed with Bromberg’s observations. Lt. Gen. David Nahom, deputy chief of staff for plans and programs, told lawmakers in April that the Air Force did not have the money to spare to reengine the F-35A.

“Given the current top line we have right now, we’re going to struggle to get any further with this technology,” Nahom said.

Newly confirmed Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall, however, embraced the fuel efficiency and thermal management advantages offered by AETP, saying in mid-September that he has directed his staff to examine the affordability of reengining if the Navy decides not to participate with their F-35Cs.

Whether Kendall’s interest is genuine or a negotiating ploy with Pratt, Bromberg says his company now is eager for a competitive face-off between GE’s XA100 and the XA101.

“We will win,” Bromberg says.

Comments

This future engine work should be focused on the F-22 replacement and whatever the Navy and Marine Corps need for a fixed wing fighter and fixed wing multi-role attack aircraft (e.g. VA/S/Q capabilities) in the future.